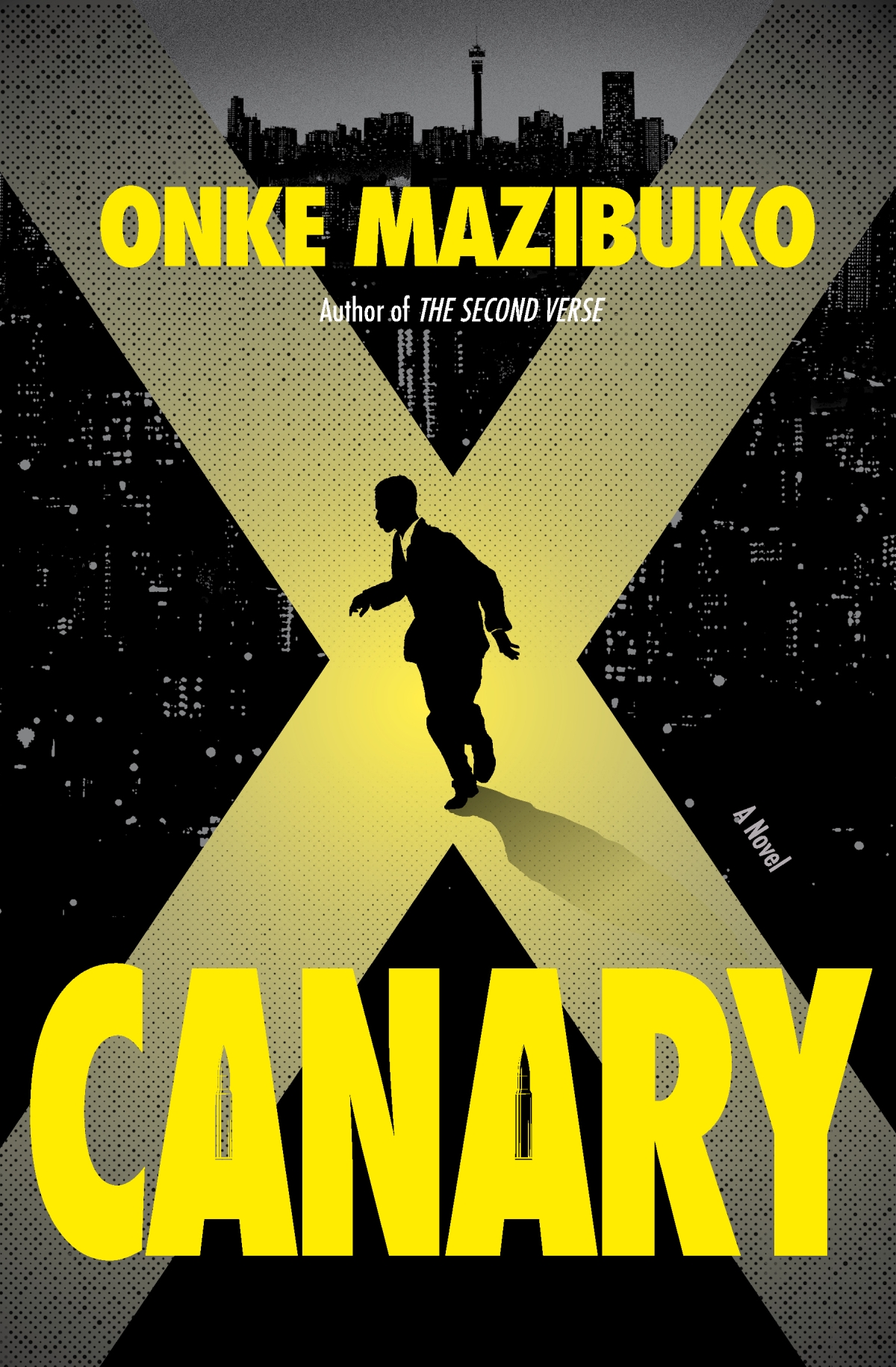

For his second novel, Canary, Onke Mazibuko dives into the fraught

world of whistleblowing in South Africa. A psychologist and educator,

Mazibuko brings firsthand insights from his time in a state-owned

entity to craft a gripping, high-stakes thriller. The novel follows Maks

Ntaka, a man who risks everything to expose corruption, only to find

himself ensnared in the very web he’s trying to unravel. We sat down

with Onke as he discussed the inspiration behind Canary, the

psychological toll of speaking out, and what South Africa needs

to do to better protect its whistleblowers.

In Canary you look at challenges surrounding (being) a whistleblower. How did the idea come about?

The idea for this story was largely influenced by my experiences as a South African. The years between the 2019 and 2024 national elections got me thinking about responsible citizenry and what things were working against national unity within the country. As someone who had never voted in previous elections – even though I was qualified to vote in three of the previous ones – I found it increasingly interesting that I was now certain that I would vote come 2024. I started asking myself more and more what I can do to change the outcomes of the country.

You have experience of working for an SOE. How did it inform the writing?

Working at a state-owned entity for twelve years was another important influence in bringing the idea for the story into reality. This was especially the case because this is one of the more prominent SOEs, always in the newspapers, and when I started there, I was in awe of the efficiency of the organisation. I honestly believed, by working there, I was contributing towards making South Africa a better country. However, over the years I worked there, it was scary to watch how quickly things changed and, in my efforts to maintain the standards and values I had been taught there, I was starting to be seen as an outsider who was a barrier to progress. While I, myself was never a whistleblower, I increasingly found myself close to situations where I could have potentially become one.

Who is this book for?

In writing the story, I also wanted the reader to ask themself if they would ever be a whistleblower. I wanted the reader to also judge the main character for their flaws and then consider if perhaps they have not been too harsh considering what the disclosures expose. I also wanted the reader to consider how complicit they are in corruption by not reporting the things that they see or hear about.

We have seen a number of whistle blowers being silenced to protect the guilty parties. What should we do (differently) in SA to protect those who speak out against corruption?

South Africa needs more positive narratives of whistleblowers. Currently whistleblowers are discussed in the media mostly when they have been assassinated but most people don't even know what they disclosed. Whistleblowing in this country is also often confused with informing, which puts negative connotations on the practice. Whistleblower narratives need to be changed and shared widely to encourage people to follow the positive examples.

Have you spoken to any ‘real’ whistle blowers as part of your research?

I was fortunate enough to meet Mike Tshishonga. He was kind enough to invite me into his home and he and his lovely wife showed the greatest hospitality. He is fortunately one of the whistleblowers whose story can be seen as successful. However, his story also highlights what a sacrifice whistleblowers make. The sad reality is that there is never a happy ending, or easy way out, for whistleblowers. They make a sacrifice that costs them so much and often the reward is not what they anticipated or what the public deserves.

“There is no single definition that fits all whistleblowers. It is better to understand them as sitting on a spectrum.”

You are a psychologist. What are the effects of living with the kind of strain Maks has to deal with, on a person?

The stress of being a whistleblower is intense. Not only does the whistleblower have to deal with an ethical dilemma, they have to deal with the scrutiny over their character and motives, deal with the consequences such as losing their jobs, being ostracised by colleagues and being labelled as traitors by those in power, but they also have to deal with the negative psychological coping mechanisms such as substance abuse, over-medicating and a general draining of their resources. In writing the story, I was interested in what happens psychologically to the whistleblower, hence the main character finds himself in so many difficult situations, all of which don't have easy outcomes.

We seem to have a mindset in SA that, as long as you’re not caught out, it is ‘ok’ to help yourself to government money. How do we address this – especially since the guilty are a very good advertisement for their lifestyle?

In South Africa it would really help everyone if more people took on a servant leadership approach towards their work, whatever it may be. If people saw themselves as helping others and building the country, then perhaps the temptation to 'steal' just for you and your family would be less enticing. The inequality in the country obviously doesn't help. Sometimes people think they are working to catch up to others who may have more or be ahead. The day we have more opportunities for more people the less fixated we may be with corruption. The reality though is that there is no country with zero corruption. It's just that in many countries there is as much of it as there are opportunities for individuals and the corruption that happens doesn't hamper the country's progression towards its stated goals.

Despite his good intentions, Maks’ private life is quite messy and it certainly doesn’t help with his focus. Why this extra turmoil?

There is no single definition that fits all whistleblowers. It is better to understand them as sitting on a spectrum. On the one end are those who are zealots with high principles and a sense of morality that would only ever see them 'do the right thing'. In the middle are those that previously never saw themselves as having principles and morals above the average person but find themselves in circumstances where they have no choice but to speak up against wrongdoing. Then there are those on the other end of the spectrum who only become whistleblowers because they have been caught out for wrongdoing and thus are trying to save themselves by reporting others. All the whistleblowers I encountered, either through reading their autobiographies or meeting them in person are the kind who fall in the first category: the zealots. I was more interested in a flawed character who is selective about his morality. I wanted to explore the question: is a good deed still a good deed if it is carried out by a flawed character?

Where do you find time to write?

The story was one part of my PhD in Creative Writing submission. It was a rewarding process to move between the manuscript and thesis over a period of three years. The learning greatly enhanced the knowledge in the story. It brought an understanding I otherwise would not have had and I am grateful for that process.

Canary by Onke Mazibuko is out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

John Boyne on Empathy, Writing, and Why Every Voice Matters