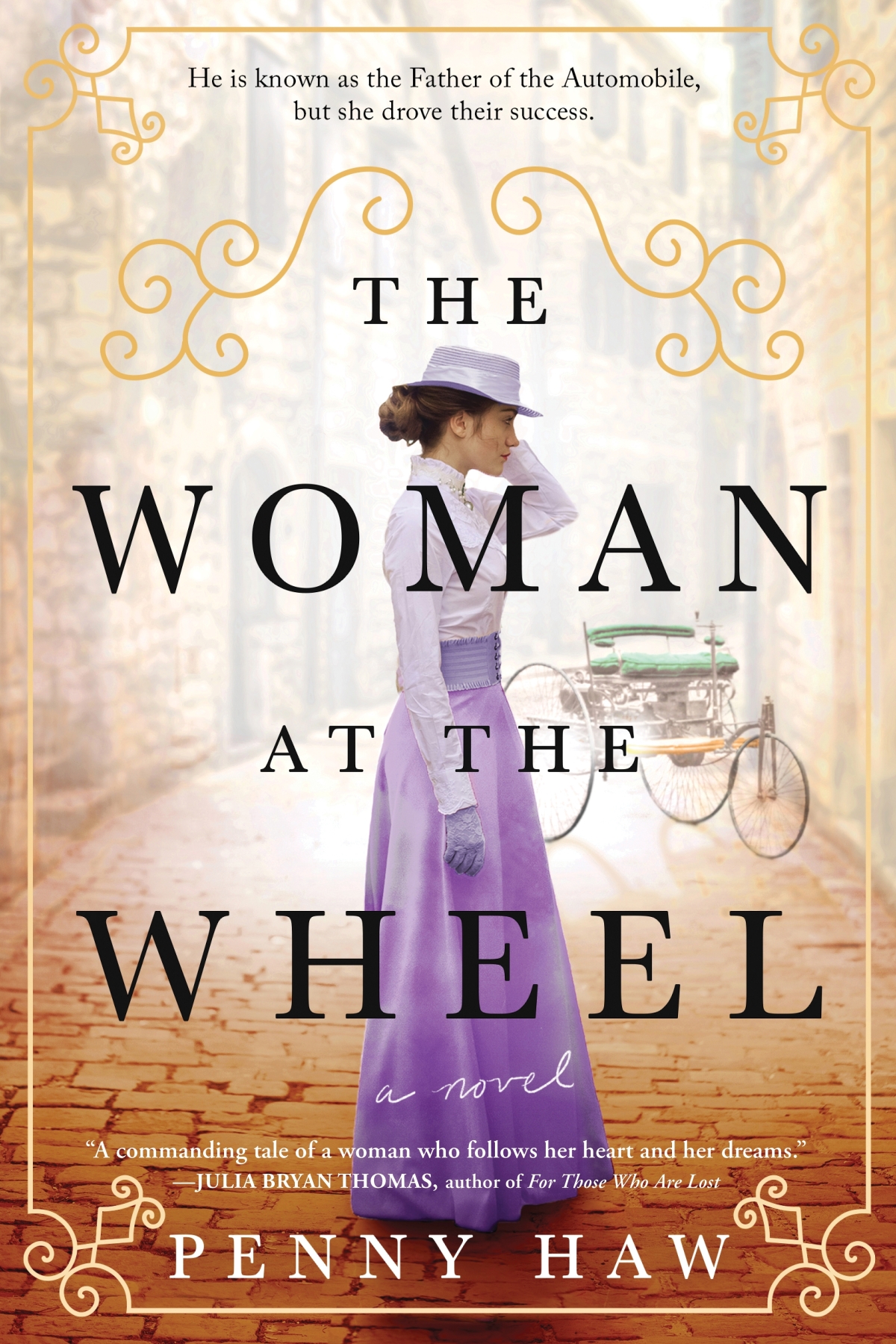

Carl Benz may be known as the "Father of the Automobile," but Bertha Benz was the woman behind the wheel driving the world into a new era. The Woman at the Wheel is a gorgeous historical fiction novel that takes a peek under the hood, examining the life of a fascinating woman who refused to let men hit the brakes on her revolutionary machine.

Chapter 1

1859

Pforzheim, Germany

I was ten years old when I fell upon five words that changed the way I saw the world.

At the time, my parents, Karl and Auguste Ringer, had seven children. Our number would rise to nine when Thekla was born in 1862, followed by Julius in 1864. Given how occupied our father was as Pforzheim’s preeminent master builder, it might’ve seemed incongruous that he had the energy to spawn so many of us. Certainly, Vater had little time to spare.

Pforzheim was already so entrenched as the hub of Germany’s jewelry and watchmaking industries that it had been dubbed the “Golden City.” Our town, on the northern edge of the Black Forest, was also abuzz with preparations for inclusion on the Karlsruhe–Mühlacker railway line. Accustomed to dodging businessmen checking their pocket watches in the streets, we were also growing used to the increased clatter of trolleys, carts, and carriages carrying materials to build the new transport system.

As they were leaving Vater’s study one day, my father and his colleagues spoke about what the railway might mean, not only for Pforzheim but also for Germany. I was halfway down the stairs when I heard them agree that the train was much more than a method of transportation.

“It’ll open new worlds to many,” said the tallest, leanest man among them. As they walked toward the front door, he explained that, whereas only the wealthy and powerful could afford to travel by horse and coach, the locomotive would allow many others to move across the country with greater ease.

I peered over the wooden handrail and saw my father and the others nodding.

“It doesn’t matter that few understand how it works,” continued the man. “When people lose their fear of the locomotive and recognize the advantages it offers, everything will change for them. Already, things are changing.”

There was more nodding and some affirmative grunting before the group disappeared, leaving me with thoughts of hordes of men, women, and children clambering into train carriages, in search of new worlds. It was exciting.

Indeed, business was booming in Pforzheim, and Vater was making the most of it. Most days, he was gone before dawn sprinkled its early light on the Enz River. He came home after the streetlamps were lit. However, when our father was with my mother, siblings, and me in the large, fashionable house he’d built us, he was generous and affectionate. Vater was also forthcoming, if rather self-engrossed, and inclined to talk primarily about his work.

His lengthy discourses about his clients (mostly wealthy), projects (largely elaborate), building materials (typically expensive), and new techniques (always brilliant) were acknowledged with indistinct mumbles and nods from my mother and sisters. My brothers were too young to feign interest. I, however, was fascinated by Vater’s work and his stories about it. I’d listen for as long as he’d talk, interrupting to beg for more details and to ask questions, which he neither shirked nor responded to with impatience.

Often, he and I became so absorbed in conversation, we’d only notice that the others had left the room when the fire dwindled and we grew cold. I didn’t understand their indifference. How was it possible they were not enthralled by the buildings Vater created, the people he met, or the role he played in the development of Pforzheim? He knew people who were establishing factories, inventing tools, and designing machines. He was watching the future of the world as it was rolled out. How exciting I found it. My mother and siblings’ disinterest made no sense to me. On the other hand, my curiosity about Vater’s work and his eagerness to satisfy it created what I believed to be a special bond between us.

“Building houses, factories, shops, and churches is only part of what I do,” he said as I walked alongside him down Karl-Friedrich Street one afternoon, a week or so after I’d overheard him and his colleagues talking about the locomotive. “I’m also an appraiser. That means I must examine the work of other builders.”

“Why should you do that?” I asked, slowing my skipping to match his step.

“Because if buildings are not constructed with care, they fail. An appraiser checks on the quality of the work,” he said.

“What kind of things do you have to check?” I asked, spotting—a moment too late—a pile of freshly deposited horse manure on the cobblestones. It was rare for me to accompany Vater on a business outing. In my excitement, I’d forgotten my mother’s rule that we should always walk on the pavement. I’d have to clean my shoes before she noticed the evidence of my carelessness.

Vater removed his hat and used it to fan his rosy cheeks. At almost sixty and burdened by a belly that seemed to expand by the day, my father was not as agile or fit as he had been.

“I’ll explain when we arrive,” he said.

We walked on without talking, crossing the small bridge toward the town square, where the pavements bustled with afternoon shoppers and the roads rattled with carriages and carts. Finally, down a quieter side street, we rounded a corner to our destination. Vater stopped in an open doorway, stomach rising and falling as he filled and emptied his lungs. The building, a jewelry workshop that was being extended, was made up of two large rooms. There was a strong smell of brick dust and wood but, aside from a few tools propped up against a wall and a low pile of planks on the floor, the rooms were bare.

“Physical activities be damned,” muttered Vater. “I will take the carriage next time.”

Finally, breathing restored, he lifted his cane and pointed to the floor. “The first thing I examine is the foundation. Without solid groundwork, a building is doomed.”

“I would be important too. I’d do something useful.”

From there on, my father described his duties as an inspector. He explained how the weight that the walls needed to support was calculated and how builders fortified them accordingly. Vater told me how window frames were fitted, edges squared, and floors sealed. He gestured at the beams and described how poles and planks were selected and treated.

I followed him into the second room, staying close so as not to miss a word. He continued talking until he was distracted by two men who—wearing glossy shoes, hats, and dark suits so tailored and neat they might’ve been painted on their bodies—entered the room.

“Stay here,” said Vater.

The three men shook hands and exchanged a few words before my father led the way around the first room. I followed, this time at a distance. The younger of the two carried a ledger and, as my father spoke, made notes with a pencil. It pleased me to see how the men—though more polished than Vater in their expensive-looking outfits, complete with gold watch chains swaying against their hips—listened and nodded attentively as he spoke. My father’s words carried weight.

The younger man seemed particularly engaged, leaning toward Vater as he spoke and then recording his words in the book. What is he writing? I wondered. Whatever his role, it appeared important. I pictured myself following my father around his construction sites, making notes about what he saw and asking questions when I was unsure. I would be important too. I’d do something useful. The only time I’d ever seen my father writing was shortly after my mother gave birth to Erwin four years ago. As I’d passed the study door, I saw Vater, quill in hand, bent over his desk. What role did writing play in his work? I was curious and decided that, at the first opportunity, I’d sneak into the study—we were not allowed to go in there alone—and see if I could find his notes. If I was going to help Vater with his work, I’d need to know what writing he required.

An hour or so later, my father heaved a sigh of gratitude when the older of the two men offered us a lift home in his carriage. As we climbed in, I examined the coach with new interest. How was it made? I wondered. Did its construction require the same deliberation as was necessary for the workshop we’d just examined? It made sense since the carriage had to be strong to carry passengers over roads, many of which would be rutted and rocky. I peered at the latch that held the door closed, marveling that someone had come up with the idea and had made and fitted it to the carriage. Would it have been a metalworker or a carpenter? As we returned along Karl-Friedrich Street, I stared out at the buildings, seeing them afresh. That so much consideration, knowledge, and skill had gone into creating each one intrigued me. How interesting life was. How much there was to learn and do.

“You took your favorite to work with you?” said Mutter, glancing up from her needlework as I followed Vater into the drawing room a short while later.

He sat down heavily in one of his favorite plushily upholstered chairs near the door and rested his cane against his knee. “Just a quick inspection close by.” He looked up. “She was the only one who chose to come.”

My older sisters, Emilie and Elise, sat on either side of Mutter, their heads bent over large sections of white cloth, through which they dipped their needles and threads in silent industry. At fifteen and thirteen respectively, my sisters were, Mutter insisted, running out of time to complete their trousseaux.

“She should begin preparing for her future like her sisters are,” said Mutter, her eyes on her needle.

Karl, who was little over a year younger than me, sat at Emilie’s feet, untangling a ball of cotton. The three little ones—Herbert, Erwin, and Amelia—were upstairs with the nurse.

Mutter glanced at Karl. “Did you not want to accompany your father, my son?”

“I was busy,” he replied, holding up the cluster of cotton. “I shall go with you next time, Vater.”

“You should,” I said as I pulled up a stool and sat near my siblings. “It’s so interesting. Vater can show you how he digs and fills foundations, and how carpenters shape wood so that the beams slide into each other and are held together.”

“What is that on your shoe, Bertha?” asked my mother.

I crossed my feet, placing the clean shoe over the soiled one, and slid them beneath the stool.

“It’s too late for that,” she said with a small scowl. “Go and clean it.”

Emilie caught my eye and shook her head.

As I walked toward the scullery, I noticed that the door to Vater’s study was ajar. I thought again about the man with the ledger. With everyone in the drawing room, it was a good time for me to slip into the office, have a look at my father’s records, and see what I might be called upon to write one day when I worked alongside him.

The study—with a large, dark desk and matching chair on a burgundy rug—was sparsely decorated. A gold clock, encased in the same dark wood as the other furniture, hung behind the desk. Rather than the rows of books and records I’d expected to find, there were a few neat piles of letters on a small bureau against the wall. The only things on Vater’s desk were a quill, a pot of ink, and the big leather-bound Bible, from which he sometimes read aloud to us after dinner.

I went to the desk and lifted the book’s heavy cover without real purpose. My thoughts were elsewhere. The clues I’d hoped to find in the study did not exist. I’d have to ask Vater about the note-taker’s role. I absent-mindedly turned a page. There, on one of the first blank pages of the Bible, my father had written his name, Karl Friedrich Ringer, in blue ink. When I turned the page, I saw that he had listed the birth of each of his children in order of our arrival. I read, running a finger beneath his spidery cursive.

“The record of my birth had an addendum. Cäcilie Bertha Ringer, born 3 May 1849. Unfortunately, only a girl again.”

Emilie Auguste Louise Ringer, born 11 December 1845.

Elise Mathilde Miethe, born 3 June 1847.

I stopped reading, my breathing suspended when I came to the third entry. The record of my birth had an addendum.

Cäcilie Bertha Ringer, born 3 May 1849. Unfortunately, only a girl again.

I stared at the words. My heart seemed to beat in time with the clock but louder. I closed my eyes for a moment, hoping that when I opened them, I’d see that I’d imagined the addition. It didn’t help; it was still there.

Unfortunately, only a girl again.

I leaned against the desk. The wood was hard and cold. The happy curiosity that had carried me into the room had vanished along with the strength in my legs. My thoughts swam in several different directions but arrived at the same conclusion: my arrival had disappointed my father. Our bond was a sham. There was no special connection.

Unfortunately, only a girl again.

Even the ink for those five words was heavier, as if my father’s misery had flowed through him, out of the quill and onto the page, thick and fast.

Only a girl.

What did Vater mean by that? I was not only anything: I was Bertha. I was the girl who listened when he reminded us—as he did frequently—how he’d been raised a parson’s son, poor and uneducated, and how he had built his business from nothing. He would describe how he’d not allowed himself to become distracted from his goal until he amassed the wealth, reputation, and enough future projects to add find a young wife and start a family to his list of tasks. Hard work and patience, he said, rewarded him—and even if he was well into his forties before he had time to attend to matters familial, look how well we lived. Vater could not have built this home for us, have us attended to by servants, and send us to school if not for his resolve. How I admired him for that. How I wanted to be like him. It had never occurred to me before that it would not be possible. Now, though, having read that I was only a girl, I saw how foolish I had been.

Instead of going to the scullery to clean my shoe, I went to the backyard to look for Affie. Acquired by Vater about a year ago to help keep the rats out of the stables and granary, Affie was an affenpinscher—or, as some preferred to say, a “monkey terrier”. Certainly, with her short, mustached muzzle; fluffy, round head; and bright eyes, she had the face and playful, curious attitude that one might associate with a monkey.

When Vater had arrived with the tiny black bundle of fur, he was stern about the fact that the puppy had a practical purpose and insisted we were not to pamper her or turn her into a pet.

However, with Vater gone so much and Mutter as enchanted by Affie as her children were, there was little chance of the dog not becoming a pet. Indeed, before long, Affie had the run of the house while our father was at work. The instant her keen ears heard the tapping of his cane on the front path, the dog jumped up, trotted down the passage, and disappeared into the scullery or yard. Even if she was stretched out in front of the fireplace in cozy slumber, Affie’s hearing never let her down. We were confident that Vater was oblivious to the dog’s indoor indulgences.

Now, as I stepped into the yard and called her name, Affie ran to me. I picked her up and crept upstairs to the bedroom I shared with Elise. The dog looked pointedly at the door as I placed her on my bed.

“I know he’s here, but he’s tired and won’t come upstairs now,” I said, shutting the door.

Affie pressed her flat nose against the bed covers, sniffed about for a bit, turned around three times, and lay down. I stretched out alongside her, running my hand over her curved spine.

“You are not only a dog, Affie,” I whispered, my father’s words still vivid in my mind. “I would never think, say, or write that. And yet I am only a girl. I might go to school, know more than Karl, and want to help Vater with his work, but I am only a girl and there is nothing I can do about it.”

The dog sighed.

“I might as well begin working on my trousseau. At least Mutter will be pleased with me.”

Affie lifted her head, ears raised. There was a light tap at the door.

“Bertha, it’s almost suppertime. Mutter says to wash and come downstairs,” said Elise.

“I’m not feeling well. I’m already in bed,” I called out, drawing a small blanket over Affie and myself.

Elise opened the door. “Shall I ask Mutter to come to you?”

“No. It’s only a small headache. I just want to sleep. It’ll be gone in the morning.”

Although Vater had not written only a girl alongside Emilie’s and Elise’s names, it applied to them, too, did it not? Did they know our lesser status? If they did, did they care? Or had Vater still been so buoyed by the novelty of becoming a parent when they were born that he didn’t experience the same disappointment that he did when I arrived?

“I see Affie, Bertha,” said my sister, her tone light.

“She’s keeping me warm. Please don’t say anything to Vater.”

Elise approached, placed her fingers on my forehead, and squinted at me. I gave her a small smile. Mutter said Elise and I were friends the moment she helped one-year-old me toddle from my crib to the nursery window. Now she patted the dog through the blanket. Affie’s tail wagged slowly against my leg.

“Why would I?” asked Elise as she left and closed the door quietly behind her.

Extracted from The Woman at the Wheel by Penny Haw, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: The Fraud by Zadie Smith