A heart-wrenching yet laugh-out-loud celebration of friendship at its imperfect and radiant best.

Prologue

“Edi. Are you sleeping?”

I’m whispering, even though the point is to wake her up. Her eyelids look bruised, and her lips are pale and peeling, but still she’s so gorgeous I could bite her face. Her dark hair is growing back in. “Wake up, my little chickadee,” I whisper, but she doesn’t stir. I look at Jude, her husband, who shrugs, runs an open palm over his handsome, exhausted face.

“Edichka,” I say a little louder, Slavically. She opens her eyes, squinches them shut again, then snaps them back open, focuses on my face, and smiles. “Hey, sweetheart,” she says. “What’s up?”

I smile back. “Oh, nothing,” I say. A lie! “Jude and I were just making some plans for you.”

“Plans like banh mi from that good banh mi place?” she says. “I’m starving.” She rubs her stomach over her johnny. “No. Not starving. Not even hungry, actually. I just want to taste something tasty, I guess.” She tries to sit up a little and then remembers the remote, and the top of her bed rises with the mechanical whirring that would be on my Sloan Kettering soundtrack mixtape, if I made one. Also the didgeridoo groaning of the guy in the room next door. The sunny lunch-tray person saying, “Just what the doctor ordered!” even when it’s weirdly unwholesome “clear liquids” like black coffee and sugar-free Jell-O.

“Banh mi can definitely be arranged,” I say. I’m stalling, and Jude sighs. He pulls a chair over by her head, sits in it.

“Awesome,” Edi says. She fishes a menu from the stack crammed into her bedside drawer. “Extra spicy mayo. No daikon.”

“Edi,” I say. “I have been madly in love with you for forty-two years. Am I going to suddenly forget your abiding hatred of radishes?”

She smiles dotingly at me, flutters her eyelashes.

“Wait,” I say. “Extra spicy mayo? Or extra-spicy mayo?”

She says, “What?” and Jude says, “Edi.” She hears it in his voice, turns to him and says, “What?” again, but I’m already starting to cry a little bit.

“Shit,” she says. “No, no. You guys.” She wrings her hands. “I’m not ready for this. Whatever this is. What is this?”

“‘A wait list?’ Jude had said. ‘Do they understand the premise of hospice?’”

Here’s what this is: Out in the hallway, Jude had asked about Edi’s treatment. “Isn’t she supposed to get her infusion today?” he’d said, and the nurse had said cheerfully, “Nope! We’re all done with that.” And so, it seemed, we were. Nobody exactly talked to us about this decision. It was like it had already happened, in some other time and place. You order a burger and the kitchen makes an executive decision in the back. “We’re out of burgers,” your server says. “There’s just this plate of nothing with a side of morphine and grief.”

Ellen, the social worker, had taken Jude and me into her office to give us a make the most of her remaining days talk—while simultaneously clarifying that this most-making would need to happen not there. We were confused. “I’m confused,” I said, and Ellen had nodded slowly, crinkled her eyes into a pitying smile, and handed us a pamphlet called “Next Steps, Best Steps.” It was about palliative care. Hospice. “But these are the worst steps,” I said, because apparently nothing is too obvious for me to mention, and Ellen passed me a box of tissues. “I feel like I’m mad at you, but also like this might not be your fault,” I said, truthfully, and she laughed and said, “I promise you I understand.” I liked her after that.

Ellen tried to help us figure out what to do. Edi and Jude’s son, Dashiell, is seven and has already spent three of those years living with his mom’s illness. Ellen wondered if bringing her home for hospice care might simply be too traumatizing, and suggested that inpatient care might be a better option, given the likelihood of a swift and harrowing end-of-life scenario. This seemed not unsensible. Dash’s last visit had been a disaster: when Edi bent to kiss him good-bye, blood had poured out of her nose and terrified him. It had just been a garden-variety nosebleed, it turned out, but Dash, already fragile, was stained. Literally stained. Figuratively scarred. “You might even have him say good-bye to her sooner than later,” Ellen offered. “So that he isn’t worrying about when it’s coming.”

“When what’s coming?” I said. The inevitability of Edi’s death was like a crumpled dollar bill my brain kept spitting back out. “Sorry,” I said a second later. “I understand.”

We called the recommended hospices from the hospital lobby, but they all had a wait list. “A wait list?” Jude had said. “Do they understand the premise of hospice?” We pictured an intake coordinator making endless calls, crossing name after name off her list. “Yes, yes. I see. Maybe next time!”

“Sloan says she’s got to be out by tomorrow midday,” Jude said, and passed me the cigarette we were splitting. We were not the only people huddled in our puff y jackets outside the famous cancer hospital, exhaling our stupidly robust good health away into the January cold, where clouds of smoke should have been gathering to form the words We’re so fucked.

“There’s a hospice up by us,” I said, and Jude looked at me unblinkingly for a few beats. I live in Western Massachusetts. He ground the butt under his heel, picked it up, and tossed it into a trash can. “It’s nice,” I said. “I’ve visited people there. It’s an actual house.”

“And?” he said.

I didn’t know. “I don’t know,” I said. “Would that be crazy? To bring her up there? I mean, they’re saying a week or two, maybe even less.”

“What would we do?” Jude said. “I really don’t want to take Dash out of school.”

“Yeah, no,” I said. “Don’t do that.”

“But I can’t leave him. Not now.”

“I know.” My hair was stuck in the zipper of my jacket, but I didn’t bother trying to get it out. My eyes were watering from smoke and cold and also from the crying I seemed to be doing.

“I don’t understand what you’re saying, Ash.”

“I know. I guess I’m not sure what I’m saying,” I said.

“Would Dash and I say good-bye to her here?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Could you?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I mean, you were at our wedding, Ash. ’Til death do us part. I can’t really imagine leaving her now—who I’d even be if I did that.”

“Jude.” I leaned forward to touch my forehead to his. “You wouldn’t be leaving her. You’d be sparing your child. Edi’s child. You’ve done ‘in sickness and health’ truly magnificently. We’d just be”—What? What would we be?—“seeing her off in stages. Tag-teaming it.”

“It’s kind of your dream,” Jude teased. “Getting her all to yourself.”

“I know!” I said. “I mean, finally!”

“You can be her knight in shining armor like you’ve always wanted.” He laughed, not unkindly. Does he love me? Yes. Do I drive him crazy? Also yes. But it was true that I’d felt stuck away up in New England, happy enough in my life there but wishing I were still in New York with everybody I’d grown up with, guiltily wishing I were closer to Edi. Now my daughters were mostly grown, and also my husband seemed to have left me. I was in the perfect place in my life at the perfect time of Edi’s. Not perfect in the normal sense, obviously.

“You’ve always accused me of being an opportunist,” I said to Jude, and he said, “True.”

We cried a little more, our puffy arms wrapped around each other’s necks and heads. Then Jude retrieved a bottle of lavender hand sanitizer from his coat pocket, gestured at me to hold out my hands, sprayed them, sprayed his own, misted his hair for good measure. I shook a couple of Tic- Tacs into his palm and mine, and we went fragrantly back in through the revolving door to wake Edi up and ask her something we hadn’t even finished figuring out. The worst question in the whole entire world, as it turned out.

“‘What on earth would happen to you?’ and she laughs and says, ‘I know, right? But just on the off chance.’”

Chapter 1

At least I’m not sleeping with the hospice music therapist.

Cedar. He’s twenty years old, twenty-five tops, and he has a voice like an angel who maybe swallowed a bag of gravel. His guitar case is covered in stickers: a smiley face, a skull, Drake, Joni Mitchell. “When you’re famous, I’m going to say I knew you when!” I said once, and it was a mistake. He shook his head, his baby forehead suddenly crosshatched with distress. I’d gotten him so wrong. “No, no,” he said. “This is it. I’m already doing the thing I want to do.”

“Of course!” I said quickly. “It’s such a perfect job for you.” And he said, “Yeah, though sometimes I dream that somebody requests something, and I’m like, ‘Hang on a sec, I don’t know that one. Let me just look it up on my phone.’ But while I’m googling ‘Luck Be a Lady’ or whatever, they die. And that’s the last thing anyone ever said to them. ‘Hang on a sec.’ ”

“Shit, Cedar,” I said, and he said, “Right?”

Now he’s sitting on the end of the bed, strumming the beginning of something. The Beatles, “Across the Universe.” Edi’s eyes are closed, but she smiles. She’s awake in there somewhere. “Cedar,” she says, and he says, “Hey, Edi,” lays a palm on her shin, then returns to his song, strumming some and singing, humming the parts he can’t remember. My heart fills with, and releases, grief in time to my breathing.

We’ve been—Edi’s been—at the Graceful Shepherd Hospice for three weeks now. Three weeks is a long time at hospice, but also, because of what hospice means, it kind of flies by. But it flies by crawlingly, like a funhouse time warp. Like life with a newborn: It’s breakfast, all milk and sunshine, and then it’s feeding and changing that recur forever, on a loop, like some weird soiled nighties circle of hell. And then somehow it’s the next day again, and you’re like, “Who’s hungry for their breakfast?” Only nobody is hungry for their breakfast. Except Edi. “Oooh. Make me French toast?” she said this morning to Olga, the Ukrainian nurse we love, who responded, “Af khorse.”

The hospice had estimated, when we checked her in, that Edi would be their guest for just a week or two. “We don’t think of this as a place where people come to die,” the gravely cheerful intake counselor had said to us. “We think of it as a place where people come to live!” “To live dyingly,” Edi had whispered to me, and I’d laughed. We all refer to the hospice as Shapely as in, “I’ll meet you over at Shapely”—because Edi, only half-awake when we were first talking about it, thought it was called the Shapely Shepherd. “Like a milkmaid in one of those lace-up outfits?” she’d said, and I’d said, “Wait. What?” And then, when I pictured what she was picturing, “Yes. Exactly like that.”

Hospice is a complicated place to pass the time because you are kind of officially dying. “Am I, though?” Edi says sometimes, when dying comes up, as it is wont to come up in hospice, and I pull my eyebrows up and shrug, like Who knows? “If anything happens to me . . .” she likes to start some sentences—about Dash or Jude or her journals or her jewelry. And I say, “What on earth would happen to you?” and she laughs and says, “I know, right? But just on the off chance.”

Sometimes the hospice physician comes through—the enormous, handsome man we call Dr. Soprano because he looks like James Gandolfini—and she says, “When do you think I can get out of here?” You can tell that he can’t tell if she’s kidding or not, probably because she’s not really kidding. “Good question,” he says, pokerfaced, rummaging through her box of edibles and breaking off a tiny nibble of the chocolate kind he likes. “Do you mind?” he says, after the fact, and then, “If anyone’s getting out of here, Edi, it is definitely you.”

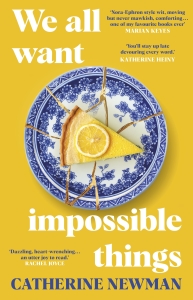

Extracted from We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

An Unforgettable and Stirring Novel for Fans of Bighearted Stories with Meaning