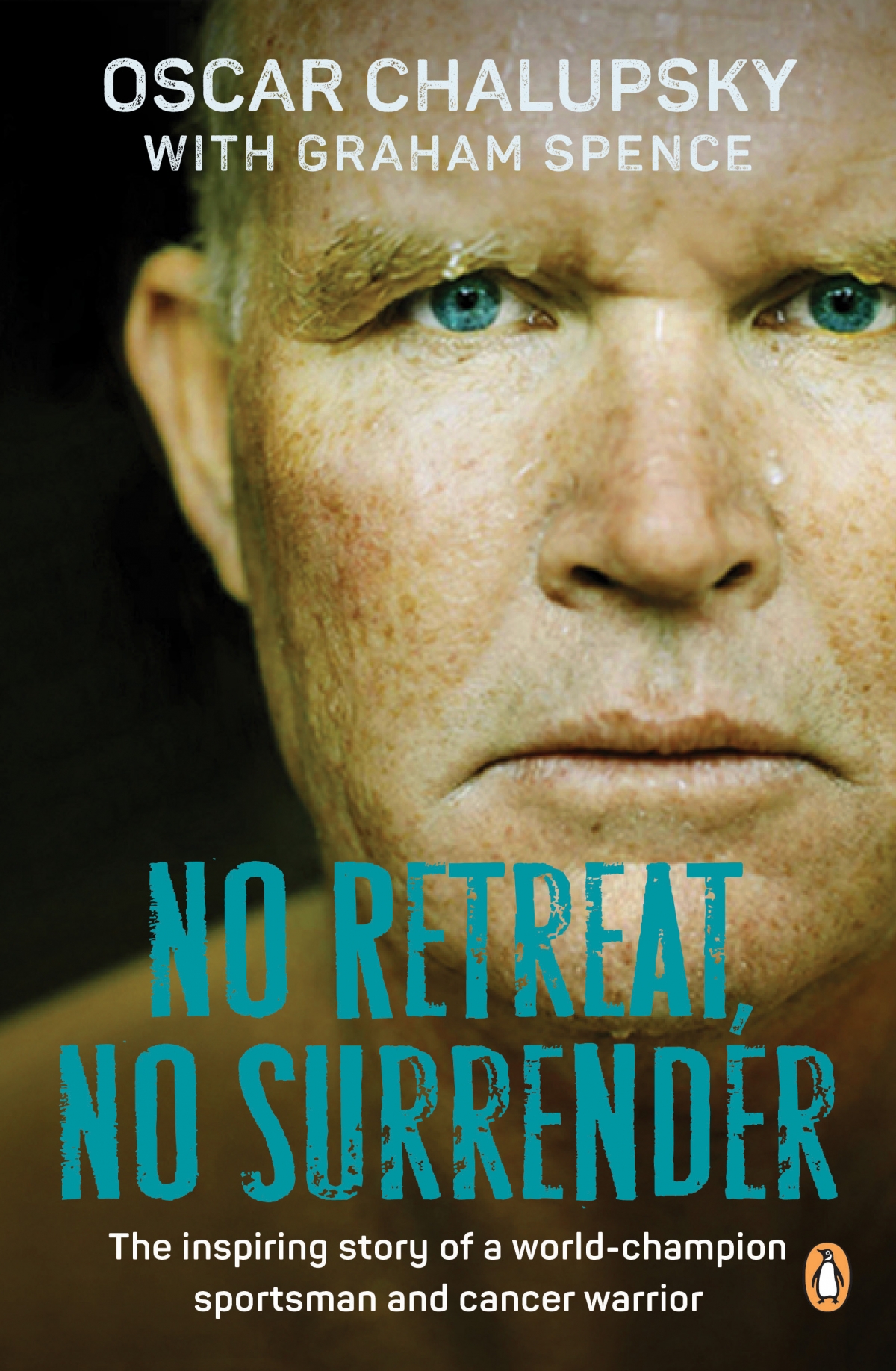

In this book, Oscar Chalupsky relives some of his most exhilarating and nail-biting races, and shares the lessons he has learnt from winning on the international surf lifesaving, kayak and surfski circuits as well as running several successful businesses. The final chapters recount his courageous battle against cancer, the vital support of his family and friends, and his refusal to let the deadly disease dictate his life.

“A shaft of agony shot down my back, like a spear being plunged into my upper spine.

It was excruciating. I had never experienced anything like it, even though my whole life as an endurance athlete had been dedicated to pushing the extremities of physical pain.

It happened while I was limbering up in the ocean for the start of the Shaw and Partners Doctor (previously called the Perth Doctor), a twenty-seven-kilometre race from Rottnest Island to Sorrento Beach in Western Australia. It’s a highlight on the global surfski calendar, attracting many of the world’s top paddlers. That year, 2019, there were 437 of us. I race it regularly and have been first across the line three times in a row.

The intensity of the spasm, rather than the pain itself, is what shocked me. I’d been nursing niggling injuries for the past two years, but this time the torment was so severe it was off the charts. I dared not admit it, even to myself, but I instinctively knew it was serious.

The race is named after the famed Fremantle Doctor, a refreshingly brisk onshore wind that brings relief to Perth residents on sweltering summer days. The irony of the name did not escape me – a doctor was exactly what I needed, but it wasn’t the wind.

I decided not to compete. That fact alone shocked me to the core. It would have been the first time in my life that I retired before the starting gun fired.

I was about to drag my surfski back onto the beach when I looked at the sky. Despite the brilliant sunshine, clouds were scudding on the horizon. The wind was gusting up to twenty knots from the south-west – a solid Force 5 on the Beaufort Scale, and perhaps later peaking to a near gale in the fresher blasts. Perfect for a fast race, which was just how I liked it.

I am known as a big downwind paddler: the stronger the blow, the better. Even though I was fifty-six years old, in squalls I believed I was unbeatable not only in my age category but in the overall race itself. The wind is nearly always strong on hot Perth afternoons, which makes The Doctor one of the fastest paddling contests in the world. It’s also, in my opinion, one of the most fun. This year could be an epic race.

Instinctively, my competitive character kicked in. I threw my flip-flops into the seconding boat that would be following the race.

‘See you guys at the end,’ I said.

The gun fired and we were off, the ocean churning to whipped cream as more than four hundred skis turbo-charged towards the Australian mainland.

I limped off the line in agony. It was one of my slowest starts ever. I needed my back to loosen up, then, hopefully, I would step on the gas. It may sound a contradiction, but the aches semi-crippling me for the past two years always lessened with exercise. That’s why I considered strenuous workouts to be the best medicine.

Not this time. The pain intensified.

I am used to beating up my body. Weekend athletes call it ‘hitting the wall’, but it’s far more profound than that. In fact, it’s the secret of extreme sports. I discovered as a teenager that we all have a mother lode of innate mental and physical steel, but to find that secret source we have to burrow into the darkest depths of our inner selves. It’s something few people wish to do, as it demands peaks of pain and exhaustion infinitely more intense than mere fatigue. The human body and mind can perform at far higher levels than most people believe. Once someone grasps that, they can do anything if they are willing to pay the price.

I certainly am not exceptional in discovering this. It’s the same almost mystical yin–yang that Special Forces soldiers, the SAS or Navy SEALs nurture when going through superhuman selection courses specifically designed to destroy even the toughest warriors.

It’s also what every world-class athlete knows. It’s the Holy Grail of endurance sport. It’s what makes us win. Coming second is just a blip, a rescheduling for next time.

But out there that day racing The Doctor with my back seized in agony, the price tag suddenly seemed too high. I decided to quit. All I needed was to signal the rescue boat to come and fetch me. I started making excuses, telling myself that I had nothing to prove. I had won the race twice, been ‘robbed’ of the title once, and invariably finished in the top ten. So why carry on?

“Wave after wave of agony exploded along my spine, and I could only get some brief respite if I stood.”

I was about to raise my hand in defeat, but something stopped me. Despite the distress, I was still in my natural element. I am happiest when surfing down fast-running swells with spray in my face and a howling wind at my back. The siren of the sea beckoned the day I got my first surfski as a young boy, and it’s a call I can never resist. Now, after close on half a century of racing to extremes, I realised I could not give up.

I instinctively found myself starting to dig deep, getting into the easy rhythm of power and flow, milking the elemental energy of every surging swell. I started reeling other racers in, but then, as I didn’t know how much harm the pain was doing to my body, I decided to throttle back and cruised to the finish.

I came fourth in the Over-50 group and thirty-fourth overall. My time was marginally over one hour and forty-five minutes, two minutes behind the category winner and ten minutes behind the overall winner. So, I wasn’t far off the pace by any means.

Once beached, I was so sore I could barely get off my ski. I had seen an expert sports physiotherapist earlier that week who said the pain was merely a pinched nerve shrinking as I cooled down after extreme exercise, so I tried to shrug it off.

However, that evening on the flight back to Portugal, the pain intensified further. I could not sit still for a minute. Wave after wave of agony exploded along my spine, and I could only get some brief respite if I stood. An Emirates flight attendant, who took customer service to new heights, filled a plastic two-litre Coke bottle with boiling water, wrapped it in complimentary airline socks, and told me to wedge that against my back.

It worked – better than any of the legion of painkillers that I had been gulping down like sweets. The rest of the fourteen-hour flight was at least bearable.

Back in Portugal, I phoned my physiotherapist, Vitor Pimenta, and asked him to book me in for an MRI the following day.

As the radiographer wheeled me into the capsule, my body started writhing uncontrollably. I frantically pushed the emergency button to be pulled out of the tube and stood for a few minutes. This happened three times before I was eventually able to lie still long enough for the machine to finish scanning.

I could tell by the startled expression on the radiographer’s face as she looked at the readings that something serious was going on.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked.

Somewhat hesitantly, she allowed me to have a look at the machine printout. ‘I’m not a radiologist, so I can’t say anything,’ she said.

She didn’t have to. Even I could see what looked to be a two-centimetre tumour on my upper spine.

‘Vitor will give you a full analysis,’ she said.

However, Vitor, who was now a close friend, was too distraught to give me and Clare the news himself. Instead he asked my business partner and former Portuguese kayak champion Manuel ‘Nelo’ Ramos to tell us the awful news. The spinal tumour was malignant. Ironically, it had been Nelo who first suggested when I returned from Australia that my problem could be cancer, but I had not taken it seriously.

I then sent the MRI images to Dr Erik Borgnes, an American radiologist who had diagnosed my long-time friend, writer and paddling enthusiast Joe Glickman a few years prior with pancreatic cancer.

Erik’s diagnosis was even more frightening. ‘The tumour is secondary cancer,’ he said. ‘Stage 3, going into Stage 4.’

In other words, it was most likely terminal. I looked at Clare, who was sitting beside me, stunned. I had been expecting bad news but not this bad.

It got worse.

‘We have no idea where or what the primary cancer is. So we cannot effectively treat the secondary cancer stage until we know what we are dealing with.’

Erik also said that the cancer had been eating away at the vertebrae, and the punishing exercise I had been doing could have snapped the bone at any moment. That would have caused instant paralysis, and he remarked that it was a miracle the spine was still intact.

‘How much longer have I got?’ I asked.

He was silent for a moment. But he knew me, and he knew that there was no point in beating about the bush. There was no easy way to answer the question.

‘Perhaps six months.’

As the shock subsided, I realised with cold clarity that everything in my life had crystalised to this point. I had a family that I loved more than anything else and a lifestyle that has no equal. I had everything to lose.

I am used to challenges. Contests are the essence of being an athlete. But this challenge was like no other I had faced.

At stake was my life.”

Extracted from No Retreat, No Surrender by Oscar Chalupsky, with Graham Spence, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Shackleton by Ranulph Fiennes