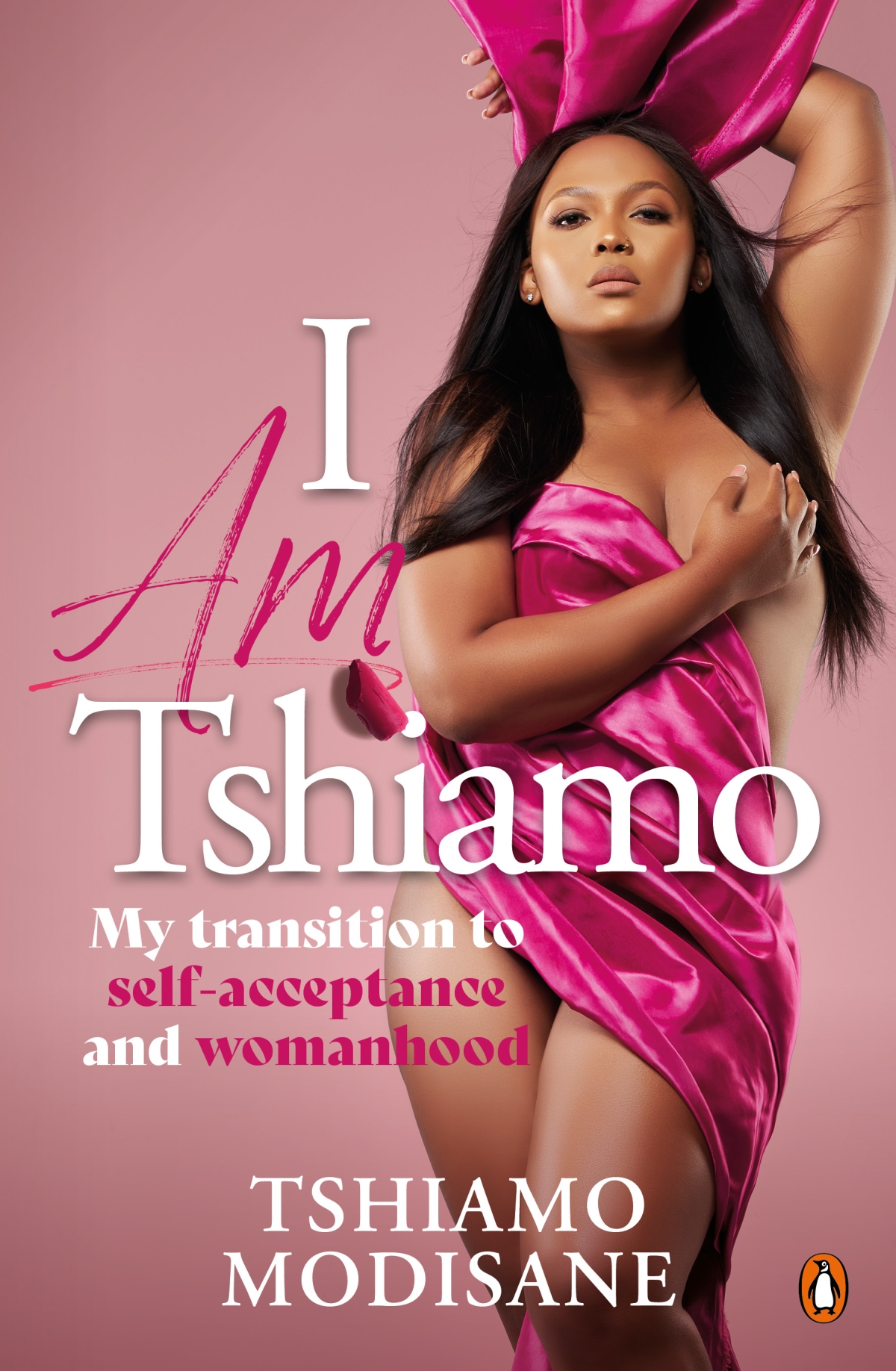

Growing up as Kgositsile, meaning “king,” Tshiamo Modisane always

knew she was a girl despite her assigned gender. Raised in conservative

black culture, she faced censure and abuse but made courageous choices

from age five. Her journey, marked by self-doubt and resilience, led to

gender-affirmation surgery in her thirties. With faith, confidence, and ties

to entertainment, she became an actress, stylist, and Lux’s first gender-

nonconforming ambassador. As admirable as it is affirming, this poignant

memoir examines past hurts and present truths, and opens up a sorely

needed discussion about unconditional acceptance.

My beginnings

‘So, tell me about yourself.’

Heck.

We’ve all heard this conversational opener at some point, perhaps during a job interview or on a date. For single women like me, the line usually rears its head on dating sites. While it shouldn’t be that big a deal or require an intellectual response – how hard can talking about yourself be? – it does make most of us stop and think about how we want to be known to the world.

For someone with as intricate a label as the one I’ve been given, it is the hardest request to answer. The tug-of-war between my true self and society has been my enduring reality. Before you start thinking, ‘What in the sociology of Deepak Chopra have I got myself into with this book?’, rest assured that mine is a very simple story, but told with a lot of questions.

From the age of five, I knew that the biological and chemical maths of my DNA were not adding up. Why was I not thinking about building a mud house after an afternoon storm or whiling away time watching the cartoons Timon & Pumbaa, Pepper Ann and Recess? My physical appearance was the opposite of how I felt emotionally and otherwise. I vividly remember being overly insecure about showing my body or simulating gender-stereotypical roles, even at a young age. I could never understand why I was always on the wrong side of the two lines that led to the communal toilets or why I couldn’t sit down when using them. To complicate matters, I was given a boldly masculine first name at birth: Kgosietsile – a common Setswana name declaring ‘The king has arrived’. Though meaningful to my dad’s sister, who had taken the liberty of christening me, my name later felt like a slap in the face.

The story behind the name goes as follows: I was the very first ‘acknowledged’ grandson in the Modisane family; my father had had a son before me but denied fathering him until much later in our lives. Therefore, my entrance into the world was heralded as the arrival of a king. I was the family’s heir and the one who would proudly carry the Modisane name forward. There’s a level of (unhealthy) red-carpet treatment afforded a woman whose first child is a boy – as though those whose first offspring are girls have done a lesser job. Most African cultures are rooted in boy children being the be-all and end-all of life – the superheroes ordained to carry the family name forward. What a cross to bear!

“I wouldn’t wish my childhood experience on my worst enemy.”

True to the many African beliefs purporting that children inherit the meaning and characteristics of their names, I guess it was long written in the stars that I would live like a king – or queen, in my case. Strong leadership skills and the ability to be empathetic yet very decisive are some of the traits that have always come naturally to me. Because I’d been named the king of the family and assumed that position, my younger brother was named Tau, a Tswana name meaning lion. I love my first name, together with its inherent meaning. But it wasn’t until age six that I learnt of my second name, Tshiamo, meaning ‘God’s complete plan’. What made it special was that it was my mother who had given me this name.

I’ve always wondered how the brain discerns between what it chooses to remember and what it refuses to acknowledge. Though I still don’t fully understand the psychology behind the staying power of memories, what I do know is that those memories linked to our internal battles often attach themselves to the innermost part of our brain. That part where they can’t be easily erased. I still remember the day my mother received a call from my teacher, ‘Auntie Kim’. I was six or seven years old, and she’d phoned to share how conflicted she was because her star pupil refused to be addressed by his first name and surname. As though that wasn’t enough, he was also showing signs of serious identity issues. During this chapter of my life, I was convinced that I shared a surname with my two elder cousins. Why? The younger of the two girl cousins resembled everything I felt and wanted to be deep down.

It killed me that I couldn’t publicly admit my appreciation for the colour yellow without immediately getting mocked for it. Or that I had to answer ridiculous questions about why I slanted my knees far back when I stood. Everything in me wanted to reply, ‘My knee reflexes are involuntary, you dummies!’ I hadn’t chosen the body I ended up with or the fact that I identified more with girls than with boys, and I wished they would understand that.

I also recall the time, when I was four or five, when my uncle took time out of his precious schedule to train me in how to walk like a man. This was to discourage me from walking as if I was a model strutting down a catwalk, something that came naturally to me. The idea of waking up daily to swim against rigid, gender-specific societal tides made every day a living nightmare. In fact, it’s recently dawned on me that I battled anxiety from as early as my nursery-school days. My anxiety and discomfort grew at each sunrise and seemed to settle at sunset, when I knew I’d have a few hours to myself. I dreaded opening my eyes in the morning because it meant facing the reality that things were just as they were when I went to sleep the previous night. To this day, I wouldn’t wish my childhood experience on my worst enemy.

Extracted from I Am Tshiamo by Tshaimo Modisane, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Blessing by Chukwuebuka Ibeh