A reluctant friendship develops between two people in an apartment block in Shanghai. Each has a secret, a hidden past that must not intrude upon the present. How To Be a Revolutionary is a bold, daring and poignant exploration of what we owe our countries, ourselves and those we love.

“The repetitive beat of typewriter keys always amplified at around one a.m., because this was the time when life on the street below stilled. Shanghai never became truly quiet. Only in the slip of time between midnight and four a.m. did the traffic recede and the noise temporarily wane. All day long the din of construction filled the air as cranes and gantries, as common to the sky as birds and planes to other cities, crisscrossed the grey. Bamboo scaffolding woven intricately as fine cotton gave shape to the vertical city, while beneath, shift workers arrived all day long, the hum and thrust of metal always in the distance.

In those months when I was new to the city and its unfathomable sounds, I knew this was the time, if any, that I would hear him typing.

The procession of taps and clicks was followed by a quick ring, a slow zip; familiar sounds that had echoed throughout my childhood when my mother brought home extra work. It kept time to my weakening eyelids until, as always, I lost the battle. There was no music now in the beat that seeped through the skin of cement, and I knew my neighbour from above used only one finger. Ayi said he was a man; she’d seen him smoking on the balcony one morning. At least I think she said this. She didn’t speak a word of English and I’d learned only the most perfunctory Mandarin: hello, goodbye, thank you, excuse me, how much for that … no, that, and so on. A combination of signs, gestures, and incomprehensible words stitched together my and Ayi’s communication about the work she had to do when she came to clean. We never said much more, and I only gleaned the bit of information about my neighbour when something crashed one morning in the apartment above, surprising us both. Ayi responded in a stream of furious indignation, gesturing my neighbour’s chain smoking and, I guessed, his goatee.

Anyway, I was certain he was a man from the way his pee hit the bowl in a steady hard stream at four a.m.

The typing kept me awake but also strangely comforted. It made up in some small way for the empty space beside me.

I had just unpacked the few groceries that I’d bought at the international store: bread, coffee, a bottle of South African wine that I’d already opened, and imported milk (the scandal where melamine had been added to dairy products to increase their weight had only just passed, people had died and everyone was still on edge).

The knocking startled me. No one besides Ayi came to my door, and the roaring bronze lion head above the polished knocker was unused.

“Good evening.”

Words emerged from the draughty passageway that sounded studied, wooden: “… I would appreciate your assistance.”

I didn’t open the door fully, even though I felt safe in the apartment, in the city.

“Sometimes it felt as if I were speaking into a body of water here: words spoken but the meaning distorted, warped in translation, even with people who had a strong command of English, so I was learning to adapt.”

“You speak English? I am looking for a word please.” I opened the door a fraction more so I could see him properly. He must have been in his early sixties I decided from the skein of silver hair that hung around his ears, while his hands, delicate and careful, were cupped before him in a question.

“I’m not sure I understand.”

“I am looking for a word … something like ‘sad,’ but not ‘sad,’” he said, shaking this idea from his head. “Something more rich.”

“You are writing something in English?” I asked. He nodded. “… Then it depends how you will use the word. What’s the context?” I said, smiling now but maintaining the door at 45 degrees. I was equally perplexed and intrigued by the stranger and wondered why, of all the doors he might have approached, he’d come to mine.

“No …” his face broke into a bemused smile, “I am sorry cannot give.”

Sometimes it felt as if I were speaking into a body of water here: words spoken but the meaning distorted, warped in translation, even with people who had a strong command of English, so I was learning to adapt.

“I mean to say I need to understand how you will use the word, so I can give you the best one.” I tilted my head. He followed suit.

“I understand,” he said, “but cannot give.”

“Well … maybe you should come inside,” I swung the door fully open, and for months after couldn’t say why I’d invited the stranger into my home. I’d made no friends in the city; hadn’t even gone to the welcome for new consular staff a few weeks earlier, and I was coming to think of my solitariness as a choice, as a decision.

He made his way into the living room and towards the windows that held the Huangpu River and its smoky vista, a filament of pink dragged right across the sky.

“It’s a good view,” I said.

“Mine the same,” he replied.

“Oh, really, you’re in the same block?” I asked, at which he pointed up. “On a higher floor?”

“One up. My view same, but better,” he smiled again.

Maybe I’d misunderstood.

“You live above me?” “Yes, right above. One up,” he said, his pointer nudging the air.

My grasp about the man began to solidify: It was him—my inconsiderate neighbour, my pertinacious typist—coming over to ask for a word? I wasn’t angry … perhaps mildly annoyed but curious; after all, hadn’t his life become part of mine, leaking into my sleep, establishing some sense of routine?

I said, “I hear you sometimes.”

“What?”

“Typing … the typing in the middle of the night.” He watched my fingers pounding invisible letters and hitting a nonexistent type bar.

“You can hear … no, you are mistaken …” he stammered. “This is not me. I do not possess.”

“Really? But I was certain the sounds were coming from above,” I said, bewilderment and, I suppose, an involuntary challenge rising in my voice.

We stared at each other.”

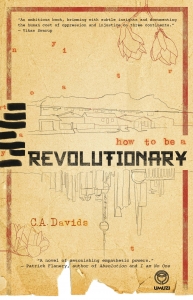

Extracted from How to be a Revolutionary by C.A. Davids, out now.