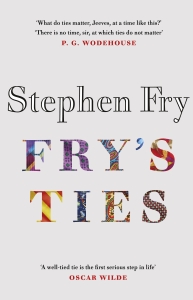

By the time he was fifteen, Stephen Fry owned more than forty ties. Inherited initially from a grandfather, matters turned more serious when he could afford to buy them brand spanking new. Inspired by Stephen's hugely popular Instagram posts, this book will feature beautiful, hand-drawn illustrations and photographs to celebrate his expansive collection of man's greatest asset: the Tie, in all its sophisticated glory.

Of Ties and Me

“Anyone can wear a tie. All you need is a neck, a shirt and a feel for colour.

Anyone can wear a tie, but few do. I am old enough to remember the time when the pavements of the City of London were populated by formidably formal figures perfectly arrayed in suit, collar and tie. Not just a collar and a tie, but a separate collar and a tie. Most of you will be too young to remember that men of all classes wore shirts with separate collars right up and into the 1960s. These were called ‘grandad shirts’ by the girls and boys two generations below, who wore them without collars as amusing hand-me-downs. They made a good nightshirt too. Grandads themselves would only have been seen like that in their most relaxed moments. For work and Sunday best they would have affixed a collar (often heavily starched). This required a front and a back stud to anchor it all in place.

Both of my deceased grandfathers and a great-uncle had left collar boxes amongst the possessions which had come to us during my boyhood. These very adult and exotic objects intrigued and excited me, with their beautifully stamped monograms and their masculine aroma of camphor, bay rum, sandalwood, tobacco and leather. The collars inside were in various styles: the usual pointed turndown collar; a variant with rounded ends; the wing (as worn by Neville Chamberlain); and the imperial, which went straight up but, unlike the wing collar, was not folded down into triangles at the ends – when properly worn, it forced the chin up high and gave one the air of a besashed and bemedalled European archduke.

As soon as I could, I took possession of these boxes (two circular and the other in a horseshoe shape) along with the collection of collarless shirts, silk and satin ties, starched collars and metal and ivory collar studs [2] that accompanied them. I worked out, by tiresome trial and irksome error, the difference between a back stud and a front, and after many tears and curses became proficient in the art of dressing myself in the manner of two generations back. Rear stud first – grunt – then slip the tie in and round – poke the tongue out to aid concentration – fold the collar down – don’t crease it – and finally, and most fiendishly, coordinate the thumb and fingers of both hands in such a way as to be able to insert the front stud without trapping the tie – fierce stamping, sweating, and foul, foul language.

Oh, it’s a fiendish and fretful business I assure you. That front stud has to be slipped through four different buttonholes – two at the collar ends, and two on the shirt where today there would be a top button – before getting a thumb or fingernail to close up the pivoting little disc at the rear. Vaguely similar to the business of doing up cufflinks, but twice as fiddly. If you managed it successfully, the tie would still be inside the collar, untwisted, and running free enough to be adjusted and tied. It was important to close the knot in such a way as to cover the stud.

I still shake my head sorrowfully at period dramas on film and television today where the knot isn’t done up fully and the stud (or worse still a button) is fully visible. Shoddy, I think to myself. Not done. Scarcely the ticket at all.

Which brings us on to the subject of me. What kind of teenager – in the fab and groovy 1960s as they whirled psychedelically into the 70s – would dress up in his grandfather’s old togs and go into town sporting a shiny stiff collar and a silk or satin tie? A teenage Lord Snooty yearning to be beaten up by the Bash Street Kids, you might think. I suppose it did take a bit of courage on my part to dress quite so oddly, though I don’t recall feeling especially brave. Perhaps I didn’t care what people thought, an indifference to opinion that I have never since been able to recapture.

Here’s the weird circle of youth and fashion. ‘Suits and ties are so yesterday,’ we declare. We have freed ourselves from convention and formality and now run about in jeans and tee shirts. But then this itself becomes a convention of its own, as parents so love to point out to their long-suffering children. ‘If you think that you’re being more individual by dressing just like the rest of your generation . . .’ And this leaves a space for the few who go backwards rather than forwards.

I am as certain as I can be that, had I been born forty years later than 1957, I would, as I grew into school age, have stood in the playground and sneered contemptuously at all those losers busy at their little screens sharing content from Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok. How lame, I would have thought – probably out loud. I like to believe that I would have been most ostentatiously

Off The Grid. ‘Sorry, sir, knowing your email address is no help. I don’t have email. I can’t deliver my homework that way. I don’t have a printer. Or a laptop. Or a mobile phone. I can produce the essay on a typewriter, or using a fountain pen? I can slip it into your actual mailbox, in the sense of the slit in your front door. Any good to you?’ My friends and I would have listened to our music on vinyl records and tape cassettes, communicated by landline telephones with dialling mechanisms and Bakelite brackets for cradles, exchanged messages by way of John le Carré one-time pads and dead letter drops, and probably produced a weird and provocative magazine using an old duplicator or mimeograph.

“My style then, if style it can be called, was a mixture of the bandstand, boater and blazer nostalgia that slowly permeated Norfolk from London, and the world of aunts, valets, cads, loungers and eccentric lords and ladies that I absorbed from my reading.”

In fuzzy type and on blue paper that would be hard for some digital doofus to scan or photocopy. And we would have thought ourselves the most excellently stylish kids in the world.

Well, born when I was, without ever perfecting stylishness I did mostly reject the fashions of my contemporaries and, where possible, exhibited myself in clothes of my grandfather’s era, as described. I played 78 discs on a wind-up record player, listened to radio and music-hall comedians rather than prog-rock titans, and read Wodehouse, Waugh, Wilde, Chesterton, Dornford Yates, Dorothy Sayers, Henty, Kipling, Mary Renault and Conan Doyle, and almost nothing by contemporary writers.

I may have been a lone weirdo as far as rural Norfolk and the medieval lanes of Norwich were concerned, but actually the Sgt. Pepper look, Chelsea bric-a-brac boutiques, and art-college groups like the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band all told of the current retro fad for big-horned gramophones, bowler hats, the hussar and dragoon military swagger, ruched parasols, Kitchener moustaches and all kinds of jumbled-up Edwardiana. My style then, if style it can be called, was a mixture of the bandstand, boater and blazer nostalgia that slowly permeated Norfolk from London, and the world of aunts, valets, cads, loungers and eccentric lords and ladies that I absorbed from my reading.

A big moment came in 1974 when the cinemas showed Jack Clayton’s production of The Great Gatsby, with Robert Redford in the title role and Mia Farrow as a shimmeringly translucent Daisy Buchanan. I went nuts for Oxford-bag trousers, high v-neck sweaters and piped blazers. As for those two-tone co-respondent shoes – mwah! My feet were already moving from size twelve to thirteen, but I squeezed myself into a pair of elevens and to hell with the pain and the pinching. By this time I was smoking ten or fifteen cigarettes a day. The everyday cheap British smokes – Embassy Regal, Player’s No. 6 and Gold Sovereign – were nothing like good enough for me. It had to be Balkan Sobranie, Sobranie Cocktail, Sullivan Powell Private Stock, Fribourg & Treyer or – if available – Passing Cloud. [3] These last, in their exquisite pink box lined with crisp tissue paper, were oval, which struck me as random and ridiculous at first, but I discovered that this flattened shape allowed them to fit into the slimmest of cigarette cases. Slim cigarette cases do not ruin the cut of a fellow’s jacket. Or coat, one should say. To whip out a case, open it, and offer it to someone while murmuring ‘Turkish this side, Virginia that’ – life could afford no greater joy.

Yes, what a pretentious tosser, what a Grade A tit. A lankhaired, lanky-limbed lovelorn adolescent with stiff collar and bagged trouserings, parading with a cane [4] up Gentleman’s Walk (Norwich’s main shopping thoroughfare) and smoking unfiltered cigarettes from a silver case – even sometimes through a telescopic holder, like some 20s flapper. At least I resisted wearing a monocle. I did happen upon one in a junk shop, but it kept falling out. Just wouldn’t hold fast in the eye-socket. I did affect a signet ring, though. And of course my desk drawer revealed even more evidence of an incipient young fogey. For my correspondence I used thick cream-coloured ‘hand-laid’ paper. [5] Scented, violet ink. Sealing wax for the signet ring.

Oh Jesus, what a wanker.

It is a mercy that I wasn’t beaten up. But Norwich-ites [6] are a tolerant bunch for the most part, and aside from a few mocking shouts in highfalutin toff tones – ‘Oh, I say, I say, I say. It’s Lord Claude, don’t you know!’ – and assorted catcalls and raspberries, I was allowed to parade unmolested.

Now, I wouldn’t want you to think that I was so assured, audacious or authentic as to dress like this all the time. This was what you might call ‘a weak pose’. A pose I could adopt and discard according to mood. There were many braver young people in the ranks of the goth, the proto-emo and the punk, not to mention the pioneering outriders in the trans arena, inspired very often by Bowie, Bolan and the so-called ‘gender benders’ of the glam rock era. I was much more cowardly. An amateur without the guts to live the look through. I suppose I was what Pinter somewhere calls ‘a weekend wanker’. [7] A paddler in the shallow end of self-exhibition. Some mornings I would dress like my brother and others of my age and class in straight-down-the-line jeans or cords, under one of those brass-buttoned RAF greatcoats that were all the rage. But on other mornings I would call for my invisible valet and desire him to lay out my finest pre-war apparel.

I forbore to top these confections off with headgear of any kind. It was ties to which I gave my greatest attention. It had begun with the grand silk examples inherited from my grandfather, but even though I wasn’t flush, I managed to find handfuls of affordable second- and third-hand neckties, bow ties and cravats at jumble sales and village fetes, [8] while strange rayon and Terylene specimens could be run to earth in charity shops and the grubbier kind of curiosity shop. By the time I was fifteen, I reckon I must have had more than forty ties. Nothing to what fills my drawers and cupboards today, but a good start.”

Footnotes

2 I’d like to think they were bone not ivory, but these were different times, for good and bad.

3 Fribourg & Treyer’s elegant shop window in the Haymarket still stands, but the displays of exquisite cartons of gold-banded cigarettes and jars of snuff have long gone. On my rare trips to London as a teenager, I would go from Fribourg’s to Sullivan Powell’s in the Burlington Arcade, then over the road to St James’s, where Davidoff’s, Dunhill’s and Astley’s could be relied upon for fine pipe-smokers’ requisites, and other arcane tobacco-related appurtenances, appliances and accessories (reamers and cleaners, for example). Thence to the gloriously Dickensian Inderwick’s on Carnaby Street and on to Smith’s snuff shop on the Charing Cross Road. All of them, alas, now alive only in the memory and a few photographic archives.

4 I loved my silver-topped stick. But I soon lost it, and had to make do with an umbrella from then on. Although, if you swing a brolly with the correct amount of restrained grace, it can still lend you the suave elan and debonair diablerie that are essential for a stylish promenade.

5 So it boasted. I was never quite sure what ‘hand-laid’ meant, but it sounded pukka.

6 Should be ‘Norvicensians’, I suppose.

7 The play Old Times, I think it is.

8 Forerunners of the car boot and yard sales that are now so popular.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles