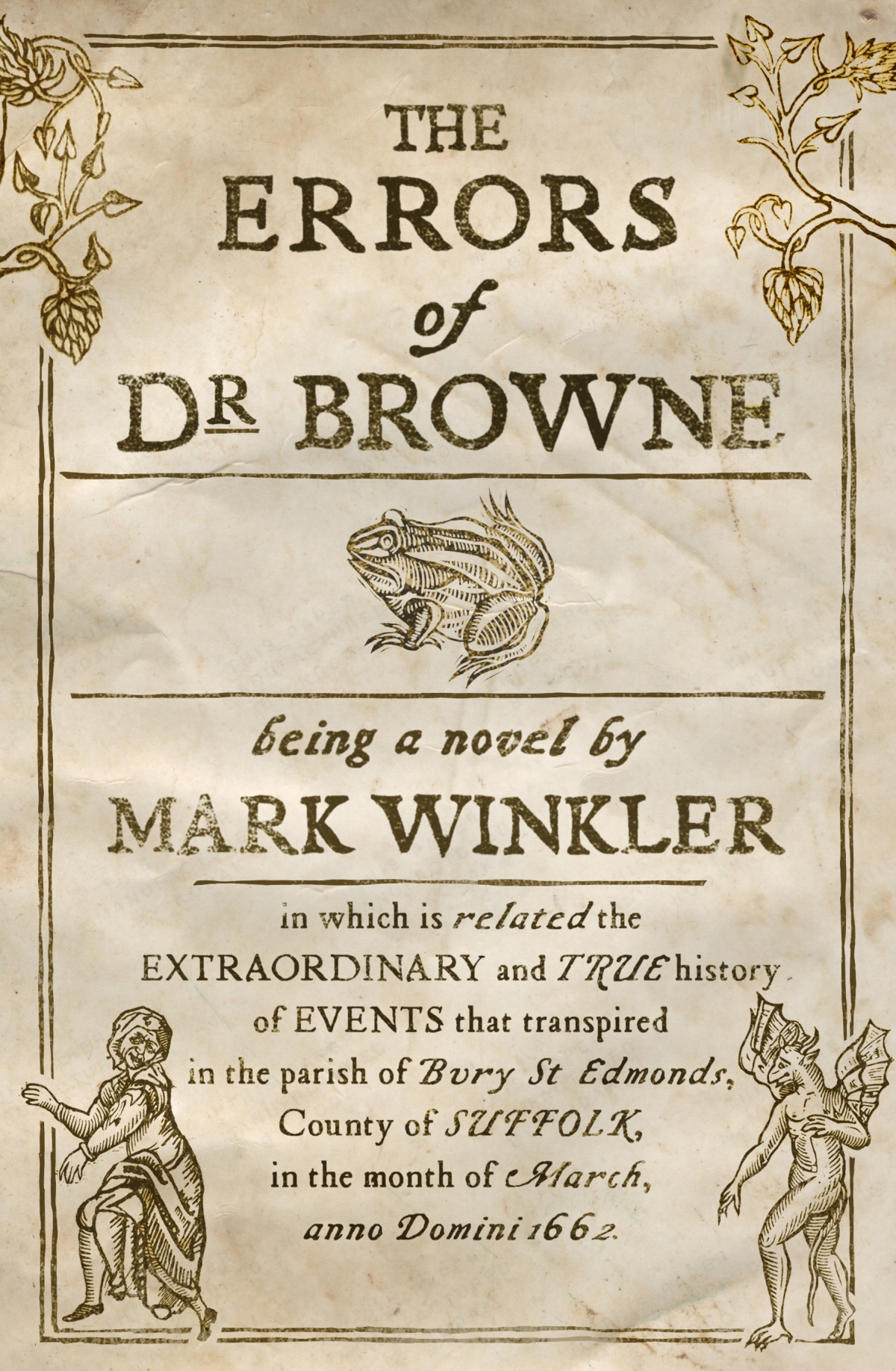

Mark Winkler’s novel is a wry and insightful glimpse into the limits of reason, the patriarchal need to control every aspect of womanhood, and our ongoing preoccupation with reputation.

‘Are you come to fetch me home, John? I am so very cold,’ Amy Denny replied, looking upon me as if for the first time, and I knew my commission of seeking a confession had come to naught, whereupon I left her and called Rose Cullender’s name into the dark.

‘A gentleman would introduce himself,’ a voice came. I sought out its source with my light, slipping in some foul and viscid substance on the way, and by my lantern I discovered a handsome, if begrimed, face of a woman around fifty, with pale eyes and hair as dark and heavy as any Gypsy’s.

‘Doctor Thomas Browne,’ I said, ‘and his clerk, Mr Charles Clark.’

‘Well, Doctor Browne and his clerk – are you going to ask me whether I am a witch?’ I brought the lantern nearer to her, the better to discern the face of such impudence, and saw upon the prominence of her cheek an angry protrusion, an ulcer or canker perhaps, though whether she had brought it to prison with her or had grown it here, I could not know.

‘I’ll begin by asking you if you understand the charges brought against you.’

‘I comprehend them, as much as one may comprehend the substance of a dream,’ Rose Cullender replied.

‘And what say you to them?’

‘That they are spiteful, but more so, foolish.’

‘How so, madam?’

‘How indeed not, Doctor? Think upon it – would I be here if I were a witch, so bitter cold in this hole with no food or drink? Surely I would simply enchant that gaoler so that he set me free, and once released, anoint a staff with belladonna and fly away on it; or indeed this very moment call upon Lucifer himself to cast aside my chains and take me from this place?’

‘There are limits, even, to the powers of a witch, thanks be to God.’

Rose Cullender snorted. ‘People like you ascribe powers when it suits you, and deny them equally.’

Such boldness, I will admit, left me silenced, and well relieved by Clark’s timely announcement.

‘Doctor Browne,’ the boy said behind me. ‘The gaoler has returned.’

I took the bread and beer from the malodorous fellow before sending him on his way. To Amy Denny, I gave a loaf and a tankard, and she fell upon it as an animal might, tearing at the bread with her gums while beer ran down her chops. Rose Cullender, for all her airs, behaved hardly better.

‘Do you know Amy Denny?’ I asked her, and with her tongue she shifted her bread to the pouch of her cheek as a squirrel would an acorn.

‘Now I do, better than I would ever wish to know anyone.’

‘You had no acquaintance with her before your arrest?’

‘None.’

‘I fear she is not of the soundest mind. Do you know what she meant about being denied the purchase of herring?’

Here, Rose Cullender laughed, although with no humour, her mouth wide and the bread white upon her tongue. ‘Such ado about seeing to one’s dinner, Doctor Browne, that it would make witches of old women for being hungry.’

‘What mean you, madam?’

“I have not eaten in some days, nor have I slept for the cold and the filth; I am quite in the mood to hurt any number of people for putting me in this situation.”

‘I mean, Doctor Browne, that, like Amy Denny, I am a widow. After my Francis died, of a worm that ate at his heart, the doctor said, I, too, was forced into solitude. Old women living on their own bear the brunt of suspicion and malice, and we have to fight harder than most men would think us capable of, simply to survive.’

‘Is that why you own a mastiff? A black-faced mastiff?’

‘I no longer have a husband to protect me. And Lucy is a fine sentry, and a trustworthy companion and confidante.’

‘You speak to your dog?’

‘And you do not? Then how does your dog come when you call her, or understand when to sit? How do you praise or reprimand her? Do you never murmur idle nonsense to her when she curls up at your feet, or when she wags her tail to see you?’

‘Nevertheless. Now, once more – do you understand the charges that have been brought against you?’

‘I comprehend them, as I said – but I do not understand them.’

‘Now I neither understand nor comprehend,’ I said.

‘Doctor Browne, if you could show me the means by which I could bring about the affliction of others, or give me the reasons to do it, this would be the time. I have not eaten in some days, nor have I slept for the cold and the filth; I am quite in the mood to hurt any number of people for putting me in this situation, but just as I am unable to call on the demons or the angels or anyone else to get me out of this place, so am I unable to entreat them to avenge me, were I chained to this wall or not. Therefore, while I comprehend the charges as they have been written down and stated to me, I do not understand why I am accused of being a witch, when it is plain to all who have eyes that I have not the craft.’

Rose Cullender looked at what remained of the crust in her hand, and less than a quarter of the loaf it was, which she carefully wrapped in her apron.

‘Yet you say you would hurt people?’ I said.

‘I would, if I could, for doing this to me, but I cannot.’

‘Are you making threats of some sort, Mrs Cullender?’

‘Most certainly – but empty ones, as they can only be.’

‘At this time, that may so. But would you seek to cause hurt in the event you are released?’

‘No, I would not, for what benefit would there be to me, other than to find myself in this corner of Hell once more? Rather, I would return to my house and my dog, and revel in my innocence and freedom, and the small pension left me by my husband, and seek to leave others to their business as I would wish them to leave me to mine.’

‘Is there something you want to say that may mitigate in your favour, come the trial?’

‘Mitigate, Doctor Browne? I have my letters, but not much learning with them.’

‘Something that may reduce the severity of the charges, I mean to say.’

‘What else, other than I am no witch, and that I have as much hope of fetching cheese from the Moon as I have of proving it to the Court?’

Extracted from The Errors of Dr. Browne by Mark Winkler, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Notes on Falling by Bronwyn Law-Viljoen