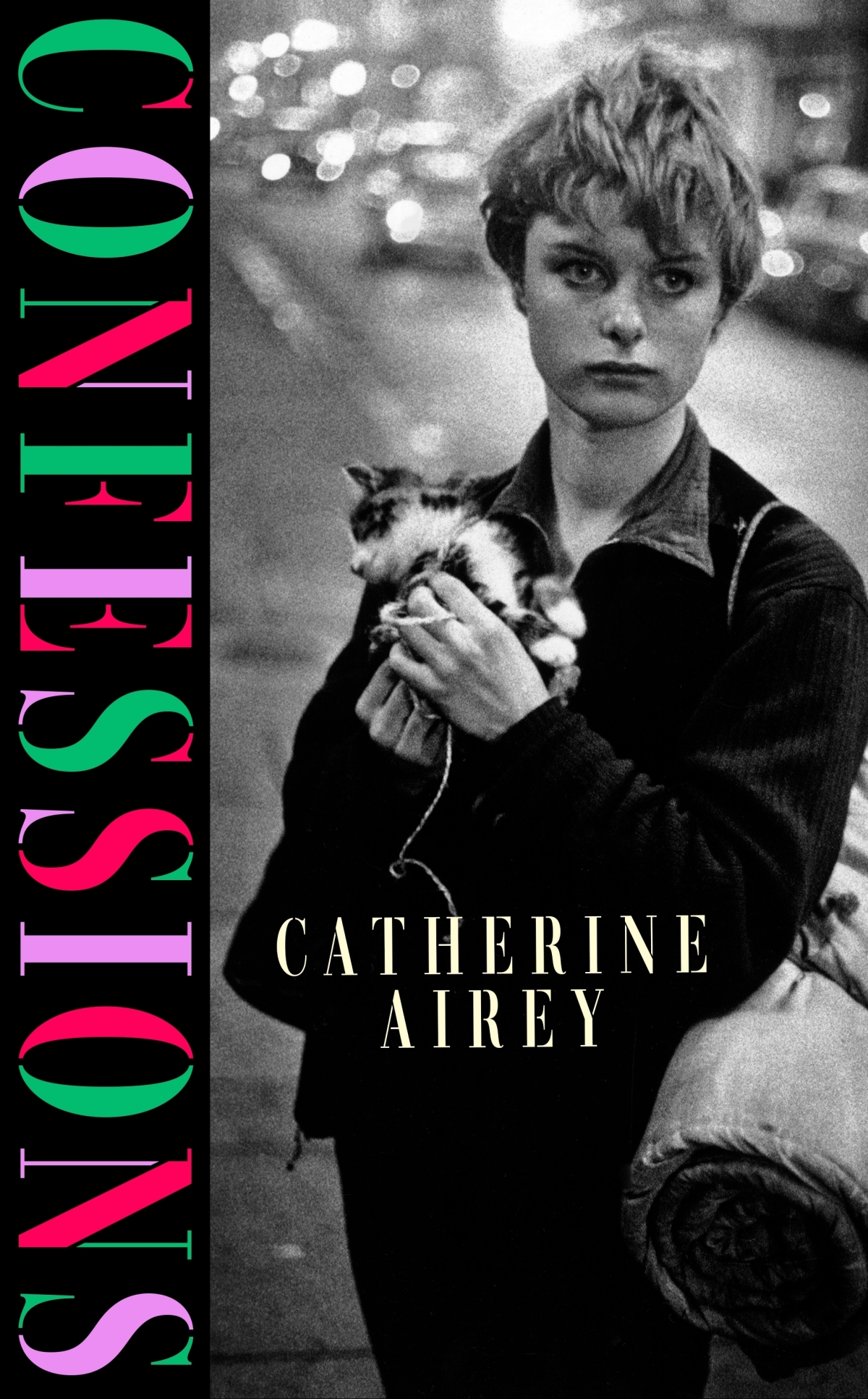

It's September 2001, and New York’s walls are covered in photos of the

missing, including Cora Brady’s father. Orphaned and alone, she is lost

– until a letter arrives offering a new life. In a remote Irish town, an

estranged aunt awaits, ready to fulfil an old promise. As Cora settles in,

her family’s buried story begins to surface. Confessions, an immersive

debut, follows three generations of women bound by love, tragedy, and

the pull of the past. In mystery and redemption, intention and accident,

it explores the beauty and shadows of the choices we make and the

histories we inherit.

Cora Brady

New York

2001

1

Two days after she disappeared, most of my mother’s body washed up in Flushing Creek. The morgue had comfy armchairs in the lobby, and I can remember being annoyed that it didn’t take longer for my father to identify the body. I was reading Little Women and would have quite happily sat there all day. I was nine.

Almost exactly seven years later, my father jumped from the 104th floor of the World Trade Center, North Tower. I don’t know that he jumped for sure, but it’s the story I’ve told myself.

I saw the photo of the Falling Man the next morning in the New York Times, along with everyone else left in the world. As well as that famous one, the photographer captured eleven others of the same man falling. Years later, when it became possible for a person to do such a thing, I inspected each photo, then pieced them together like a kineograph to see the man in motion, tumbling over and over.

For a while it was accepted that the man had been a pastry chef working in the Windows on the World restaurant. Later they said he was a sound engineer, brother to a singer who had been in Village People. They never said it was my father. I never told anyone that I thought it could be him – not just because the chances of it being true were next to none, but because I knew I wouldn’t have been able to handle being proved wrong.

If someone were to somehow not know what had happened that day, and simply seen that photo, they’d be forgiven for thinking it must be showing some kind of stunt.

In 1974, a man had walked between the tops of the two towers on a wire tightrope. The following year, a different man dressed up as a construction worker made his way to the roof of the North Tower and jumped off, attached to a parachute. Two years after that, a third man scaled the side of the South Tower. It took him less than four hours to reach the top. None of these men were harmed.

I knew all about these stunts because I’d done a homeroom presentation on the towers once in elementary school. I remember asking my parents (my mother was still alive at the time) if they remembered any of this happening, but they told me that they weren’t even living in New York at that point. The main thing they seemed to recall about coming to the city was the garbage strikes – piles of trash, eight feet high along the sidewalks. But what did I care about trash?

***

When the first plane hit, I was waiting for Kyle to come over. We’d spent the summer taking drugs and having sex in my apartment while my father was at work. I was sup- posed to be going into Junior Year, but in the week since Labour Day I’d stayed at home deleting voicemails left by the school.

Mr Brady, this is Principal Green calling from Our Lady of Perpetual Help. Cora wasn’t in roll call today, again. Could you please call back.

By the time I got up, my father had already left for work. I showered, brushed my teeth and put on a dress I didn’t think Kyle had seen yet. It was navy with little ladybug dots on it. The weather was perfect, the sky such a fearless blue. I was going to try to persuade Kyle to walk as far as Coney Island. But I could already imagine him calling it ‘Phoney Island’. I liked it there – the playground of the world. My favourite film at the time was Annie Hall and they’d recently taken down the roller coaster that had been featured in it. I wanted to see what kind of presence its absence had created. I liked the fact that Coney Island was always changing and yet somehow felt the same. I wanted to walk along Surf Avenue and for Kyle to see me sparkling in the sunlight. I wanted summer to never end. I wanted to pretend.

I checked the time on the microwave. Kyle was late. I hated waiting for things, because I was always on time or early. So was my father. He said it was an incurable illness I’d inherited from him.

There was a bowl of dry oatmeal on the kitchen island. My father prepared it each morning to encourage me to eat breakfast, as if the effort of pouring out the oats from the packet was the thing stopping me from eating. I added what was left of the milk to the bowl and put it in the microwave, set the timer for two minutes and stared at the bowl spinning round and round through the darkened glass.

I was pissed at Kyle. He didn’t have a cell phone and used this as an excuse to show up well after we’d agreed.

I would remind him that people did manage to be on time before they were invented and that, actually, if he did have one he’d at least be able to let me know how late he was going to be. But he thought cell phones were going to rot everyone’s brains and make them impotent, that they were invented to control the world’s population which was getting out of control. The anticlimax that had been Y2K was still a sore point for him.

“Witnesses at the scene said they heard an explosion. We are still waiting to confirm exactly what the cause of that explosion was.”

The timer on the microwave went off. I stirred the oatmeal and put it on for another minute, then looked around for the remote so I could watch TV while I waited. Kyle had been four hours late once, with some excuse about the subway being down and after that being searched by the cops. He said I didn’t live in the real world. Sometimes he called me ‘princess’ and I didn’t know if he was saying it because he cared about me or because he didn’t. He liked the fact that I had money and an apartment that was empty most of the time, the fact that the refrigerator was usually full and that I had my own room. He said he liked my body and the way that I smiled and the smell of my hair. But if I asked him how many girls he’d slept with before me or if he saw any of them still, he would get mad and say I was such a kid and I wouldn’t see him for a while. He’d show up in the end pretending nothing had happened and I’d pretend like nothing had happened too because I’d been going crazy for three days wondering if I’d ever see him again.

Once he yelled that nothing bad had ever happened to me and that made me cry. He told me to ‘turn off the waterworks’ and I realized I could play my mother like a trump card, my get-out-of-jail-free, the ace up my sleeve. It worked.

I knew that I had used her death for my advantage, and wondered if doing so would come back to bite me. I suppose it did.

Call it fate, call it karma, call it cosmic justice keeping the universe in balance. Belief in whatever it was would leave me making stupid bargains in my head. If I could just do X then maybe Y would happen. If I went out and walked for an hour and didn’t step on any of the cracks then maybe Kyle would be waiting outside when I got back. If I fasted for a day then I’d hear from him the next morning. Often these bargains didn’t work out, or I wouldn’t stick to my end of them, but I’d still make them with myself – with God or whatever.

My mother had been a Catholic and took me to mass when I was growing up. I found it hard to breathe there. Perhaps it was the incense. When I told her this she started crying so I didn’t mention it again. When I got older, I assumed she’d been upset because she thought I had asthma or something, but she never took me to a doctor to get my lungs checked out. I still get the same breathlessness whenever I am feeling anxious. I know now that it’s just my body reacting to feeling out of control, but at the time I took it as a sign that God was there, sitting on my chest. Those were the moments when He might be bargained with, I thought.

As I got older, the nature of these bargains began to change. Instead of promising to do a good thing in exchange for something I wanted, I would do a bad thing on purpose. I don’t know what the rationale behind this was. Perhaps I wanted to prove that God wasn’t real rather than to trust in His existence. How many bad things could a person do, I wondered, before the universe would seek them out in some way? I suppose I just wanted to be seen – for something, or someone, to intervene.

The remote was between the cushions on the couch, where Kyle had taken my virginity and I’d had to soak the cushion cover in the sink to try and get the bloodstain out after. I forgot you were supposed to use cold water, not hot. When my father got home that evening I told him it was tomato sauce. He probably thought I was on my period, so he didn’t question it. Sometimes when I lied to him I’d hope that he would question it, but he never did.

The timer had gone off on the microwave again. I wasn’t hungry. I was angry. There was still time for me to go to school, to cut Kyle off and turn my life around. I know now that it was too late for my father to survive, that it had already happened. But I still blame myself for what I did next, still believe that if I’d made a different decision it might have changed everything, stopped everything.

I did it because I wanted to feel different to how I felt then, waiting. I went to where I’d stashed the acid tabs, between pages 100 and 101 in my copy of Beloved. I took one out and put it in my mouth. I held it underneath my tongue like Kyle had told me to the first time I had taken it.

‘Hold it there for ten minutes, princess,’ he had said.

I shut the book and put it down on the coffee table. I turned on the TV and went to get my oatmeal from the microwave, even though I knew I wasn’t going to eat it. I heard the news reporter before I saw the footage.

Witnesses at the scene said they heard an explosion. We are still waiting to confirm exactly what the cause of that explosion was. As you can see, there is currently a lot of smoke coming out of the World Trade Center, North Tower.

“I knew I couldn’t stay in hell for ever. I wasn’t strong enough.”

2

Worrying about my father is one of my clearest childhood memories. Well, actually, witnessing my mother worrying about my father after the World Trade Center bombings in 1993. He was fine, obviously, but my mother was frantic waiting for him to call. The memory is specific not because I really understood what was going on, but because it was the first time I was fully conscious of trying to stay calm for the sake of my mother, as she paced up and down beside the phone in our apartment. I stood, still as a statue, out of her way, staring at the hour hand on the clock in the kitchen, trying to catch it moving.

My mother suffered from agoraphobia, hypochondria, paranoia – and many other ia’s. Because she didn’t like to leave the apartment much, my father and I would go off on trips – just the two of us, walking. She’d fret that it wasn’t safe. He’d insist it was important that I didn’t become one of those city kids with no experience of surviving in the open. We’d sleep up in mountains in a tent and cook canned food on a Primus stove. I wasn’t afraid of bears or cougars. I knew what I should do if I came across a rattlesnake: stay calm, don’t panic. There’s a photo of me with my arms wide trying to stretch around a giant tree trunk during Redwood Summer. Another of me lying on my front at the edge of the Grand Canyon, looking down, a New York Giants cap backwards on my head.

***

As I turned to face the TV, a line I’d rehearsed from that homeroom presentation, about the Twin Towers stunts, started playing in my head.

The Twin Towers are taller than the highest redwood, but no way near as deep as the Grand Canyon.

I thought that if I didn’t move the phone might ring. Or perhaps if I didn’t breathe? As I watched the second plane slice into the South Tower, I remembered what I’d done, put my finger under my tongue. The yin-yang symbol had blurred into a black hole on my fingertip. The paper had pretty much dissolved.

I figured I had about an hour before I’d really feel the acid – an hour for my father to call, for Kyle to show up. I grabbed my cell phone, left the door on the latch and headed for the stairs. When I got out on to the roof I could see smoke trailing from the towers, seemingly straight over the East River to Brooklyn. It smelt like burning wire. There were other people up there too, all of us staring at the same thing, like we’d been hypnotized.

I tried calling my father’s office number. Then his cell. Both played back arpeggios that sounded like the end of the world.

Dum di dah. Dum di dah.

I waited. Tried again.

Dum di dah.

I closed my eyes and counted. I made all kinds of promises. But I knew they wouldn’t work this time, that I couldn’t undo what I had done, unsee what I had seen.

‘There must be hundreds dead,’ someone said. ‘Thousands,’ said someone else.

‘Do you reckon anyone can get out from above where the planes went in?’

‘Man, I wouldn’t even believe a movie where this happened.’

I began to panic like my mother did on the day of the bombing. My breath caught in my chest. I was burning up. Even my arms began to bead with sweat. When the South Tower collapsed I thought I must finally be hallucinating. The cloud of dust and debris was alive, breathing, colour streaming from what I could see of the North Tower like a rainbow, then all the colours turning red, the red spreading, filling up the sky, closing in on me. I turned and ran back through the fire door, hoping I could shut the red out behind me. But I was too late. It followed me down the stairs and into the apartment. I was gasping for breath. I held my hands over my face but I could feel it entering my mouth through the gaps between my fingers, possessing me. My ears began to ring. My vision was static, like bad-quality video. The grains of red were shuddering and each had its own high-frequency voice, like they were all whispering, laughing. The picture on the TV had turned red too and when I closed my eyes the insides were like fireballs.

The voices became screams when the North Tower fell too. I turned off the TV and closed my eyes, covered my ears with my hands and thought about how ostriches bury their heads in the sand.

I crawled over to the answering machine, on my hands and knees. Nothing. I unplugged the phone and sat in the corner of the room, knees pulled into my chest. I pleaded with the Devil for some kind of grim trade. But I knew I couldn’t stay in hell for ever. I wasn’t strong enough.

I remembered the pills Kyle had given me to look after, how he’d said people would pay a fortune for just one to help them sleep after festivals and raves.

‘Sweet, dreamless, sleep,’ he would say when people asked him what they did.

We’d never taken them together because I didn’t want to sleep when I was around Kyle. What I liked about getting high together was that it would keep us both awake. I wanted to stay up with Kyle for ever.

I was hiding the bottles behind where I kept my sanitary pads, which I never used and knew my father would never touch. I found the pills, poured three into my hand and swallowed them at the sink, being careful not to look in the mirror.

I thought about the way my father helped me fall asleep when I was little. We would play what he called the alphabet game. First, we would come up with a category, then take turns going through the alphabet, thinking of something in that category that began with each letter.

American Cities, I thought. Anchorage, Boston, Chicago ...

I went to my room.

Denver, El Paso, Fargo ...

I hardly made it any further.

Extracted from Confessions by Catherine Airey, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: We All Live Here by Jojo Moyes