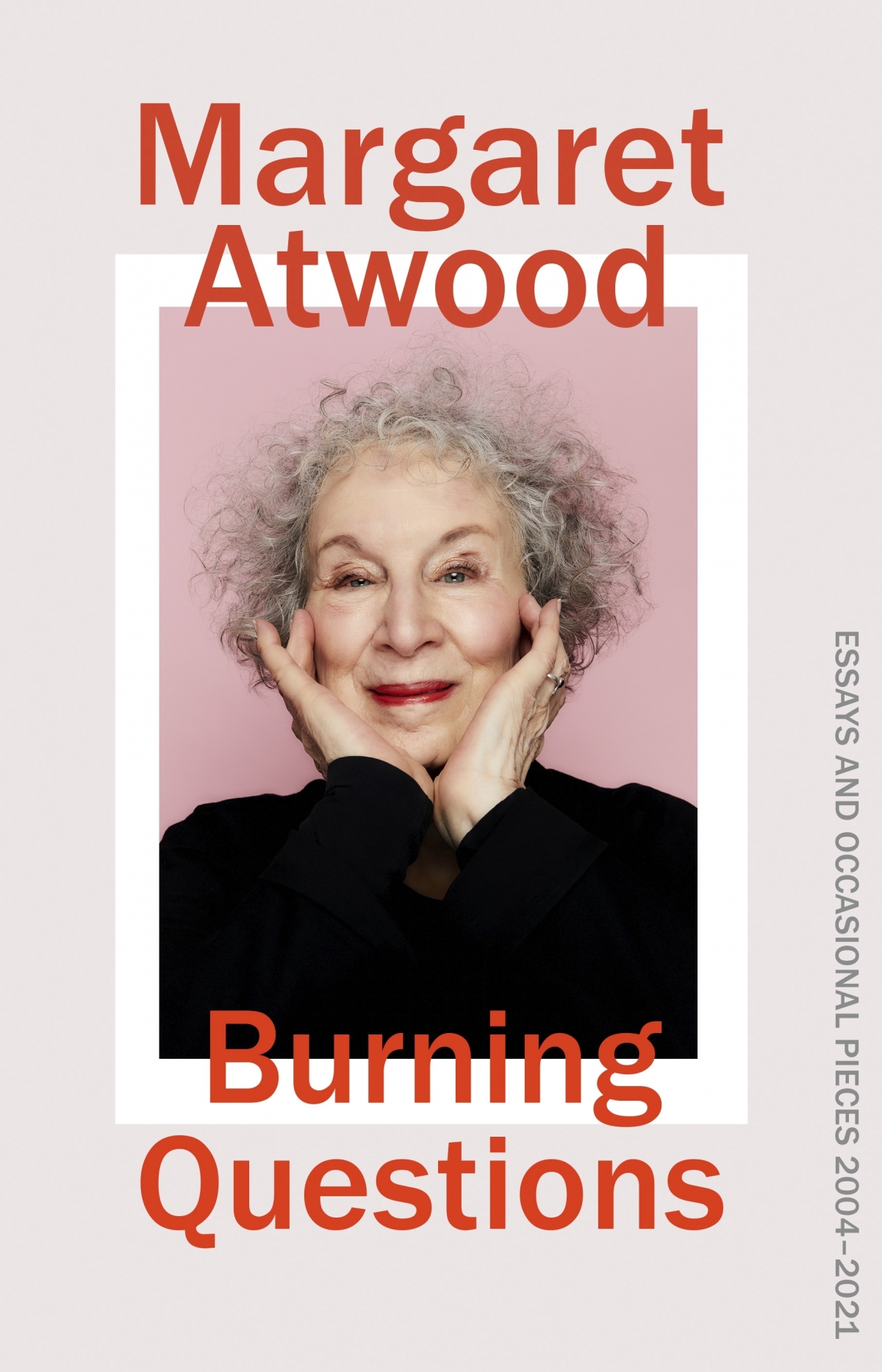

An exhilarating collection of non-fiction from the bestselling, double Booker Prize-winning phenomenon. In over fifty pieces Atwood aims her prodigious intellect and impish humour at the world, and reports back to us on what she finds.

Frozen in Time

INTRODUCTION (2004)

"Frozen in Time by Owen Beattie and John Geiger is one of those

books that, having once entered our imaginations, refuse to go away.

It made a large impact, devoted as it was to the astonishing revelations

made by Dr. Owen Beattie— including the high probability

that lead poisoning had contributed to the annihilation of the ....

Franklin expedition.

I read Frozen in Time when it first came out in 1987. I looked at

the pictures in it. They gave me nightmares. I incorporated story and

pictures as a subtext and extended metaphor in a short story called

“The Age of Lead,” published in a 1991 collection called Wilderness

Tips. Then, some nine years later, during a boat trip in the Arctic,

I met John Geiger, one of the book’s authors. Not only had I read

his book, he had read mine, and it had caused him to give further

thought to lead as a factor in northern exploration and in unlucky

nineteenth-century sea voyages in general.

Franklin, said Geiger, was the canary in the mine, although unrecognized

as such at first: until the last years of the nineteenth century,

crews on long voyages continued to be fatally sickened by the lead

in tinned food. He has included the results of his researches in this

expanded version of Frozen in Time. The nineteenth century, he said,

was truly an “age of lead.” Thus do life and art intertwine.

Back to the foreground. In the fall of 1984, a mesmerizing photograph

grabbed attention in newspapers around the world. It showed

a young man who looked neither fully dead nor entirely alive. He

was dressed in archaic clothing and was surrounded by a casing of

ice. The whites of his half-open eyes were tea-coloured. His forehead

was dark blue. Despite the soothing and respectful adjectives applied

to him by the authors of Frozen in Time, you would never have confused

this man with a lad just drifting off to sleep. Instead, he looked

like a blend of Star Trek extraterrestrial and B-movie victim-of-a-curse:

not someone you’d want as your next-door neighbour, especially

if the moon was full.

Every time we find the well-preserved body of someone who

died long ago—an Egyptian mummy, a freeze-dried Incan sacrifice,

a leathery Scandinavian bog-person, the famous ice-man of the

European Alps—there’s a similar fascination. Here is someone who

has defied the general ashes-to-ashes, dust-to-dust rule, and who

has remained recognizable as an individual human being long after

most have turned to bone and earth. In the Middle Ages, unnatural

results argued unnatural causes, and such a body would have been

either revered as saintly or staked through the heart. In our age, try

for rationality as we may, something of the horror classic lingers:

the mummy walks, the vampire awakes. It’s so difficult to believe

that one who appears to be so nearly alive is not conscious of us.

Surely—we feel—a being like this is a messenger. He has travelled

through time, all the way from his age to our own, in order to tell us

something we long to know.

The man in the sensational photograph was John Torrington, one of

the first three to die during the doomed Franklin expedition of 1845.

Its stated goal was to discover the Northwest Passage to the Orient

and claim it for Britain; its actual result was the obliteration of all

participants. Torrington had been buried in a carefully dug grave,

deep in the permafrost on the shore of Beechey Island, Franklin’s

base during the expedition’s first winter. Two others—John Hartnell

and William Braine—were given adjacent graves. All three had been

painstakingly exhumed by anthropologist Owen Beattie and his

team, in an attempt to solve a long- standing mystery: Why had the

Franklin expedition ended so disastrously?

Beattie’s search for evidence of the rest of the Franklin expedition,

his excavation of the three known graves, and his subsequent

discoveries gave rise to a television documentary, and then—three

years after the photograph first appeared—to Frozen in Time. That

the story should generate such widespread interest 140 years after

Franklin filled his freshwater barrels at Stromness in the Orkney

Islands before sailing off to his mysterious fate was a tribute to the

extraordinary staying powers of the Franklin legend.

“They knew the rules: going to an Otherworld was a great risk. You might be captured by non-human beings. You might be trapped. You might never get out.”

For many years the mysteriousness of that fate was the chief drawing

card. At first, Franklin’s two ships, the ominously named Terror

and Erebus, appeared to have vanished into nothingness. No trace

could be found of them, even after the graves of Torrington, Hartnell,

and Braine had been found. There is something unnerving about

people who can’t be located, dead or alive. They upset our sense of

space—surely the missing ones have to be somewhere, but where?

Among the ancient Greeks, the dead who had not been retrieved

and given proper funeral ceremonies could not reach the Underworld;

they lingered in the world of the living as restless ghosts. And

so it is, still, with the disappeared: they haunt us. The Victorian age

was especially prone to such hauntings, as witness Tennyson’s In

Memoriam, its most exemplary tribute to a man lost at sea.

Adding to the attraction of the Franklin story was the Arctic

landscape that had subsumed leader, ships, and men. In the nineteenth

century, very few Europeans—apart from whalers—had ever

been to the Far North. It was one of those perilous regions attractive

to a public still sensitive to the spirit of literary Romanticism—

a place where a hero might defy the odds, suffer outrageously, and

pit his larger-than-usual soul against overwhelming forces. This Arctic

was dreary and lonesome and empty, like the windswept heaths

and forbidding mountains favoured by afficionados of the Sublime.

But the Arctic was also a potent Otherworld, imagined as a beautiful

and alluring but potentially malign fairyland, a Snow Queen’s

realm complete with otherworldly light effects, glittering ice palaces,

fabulous beasts—narwhals, polar bears, walruses—and gnome-like

inhabitants dressed in exotic fur outfits. There are numerous drawings

of the period that attest to this fascination with the locale. The

Victorians were keen on fairies of all sorts; they painted them, wrote

stories about them, and sometimes went so far as to believe in them.

They knew the rules: going to an Otherworld was a great risk. You

might be captured by non-human beings. You might be trapped.

You might never get out.

Ever since Franklin’s disappearance, each age has created a Franklin

suitable to its needs. Prior to the expedition’s departure there

was someone we might call the “real” Franklin, or even the Ur-

Franklin—a man viewed by his peers as perhaps not the crunchiest

biscuit in the packet, but solid and experienced, even if some

of that experience had been won by bad judgment (as witness the

ill-fated Coppermine River voyage of 1819). This Franklin knew his

own active career was drawing toward an end, and saw in the chance

to discover the Northwest Passage the last possibility for enduring

fame. Aging and plump, he was not exactly a dream vision of the

Romantic hero.

Then there was Interim Franklin, the one that came into being

once the first Franklin failed to return and people in England realized

that something must have gone terribly wrong. This Franklin

was neither dead nor alive, and the possibility that he might be either

caused him to loom large in the minds of the British public. During

this period he acquired the adjective gallant, as if he’d been engaged

in a military exploit. Rewards were offered, search parties were sent

out. Some of these men, too, did not return.

The next Franklin, one we might call Franklin Aloft, emerged

after it became clear that Franklin and all his men had died. They

had not just died, they had perished, and they had not just perished,

they had perished miserably. But many Europeans had survived in

the Arctic under equally dire conditions. Why had this particular

group gone under, especially since the Terror and the Erebus had

been the best-equipped ships of their age, offering the latest in technological

advances?

A defeat of such magnitude called for denial of equal magnitude.

Reports to the effect that several of Franklin’s men had eaten several

others were vigorously squelched; those bringing the reports—such

as the intrepid John Rae, whose story was told in Kevin McGoogan’s

2002 book, Fatal Passage—were lambasted in the press; and the

Inuit who had seen the gruesome evidence were maligned as wicked

savages. The effort to clear Franklin and all who sailed with him of

any such charges was led by Lady Jane Franklin, whose social status

hung in the balance: the widow of a hero is one thing, but the widow

of a cannibal quite another. Due to Lady Jane’s lobbying efforts,

Franklin, in absentia, swelled to blimp-like size. He was credited—

dubiously—with the discovery of the Northwest Passage, and was

given a plaque in Westminster Abbey and an epitaph by Tennyson.

“Beattie’s team found human bones with knife marks and skulls with no faces.”

After such inflation, reaction was sure to follow. For a time in the

second half of the twentieth century we were given Halfwit Franklin,

a cluck so dumb he could barely tie his own shoelaces. Franklin was

a victim of bad weather (the ice that usually melted in the summer

had failed to do so, not in just one year, but in three); however, in the

Halfwit Franklin reading, this counted for little. The expedition was

framed as a pure example of European hubris in the face of Nature:

Sir John was yet another of those Nanoodles of the North who came

to grief because they wouldn’t live by Indigenous rules and follow

Indigenous advice—“Don’t go there” being, on such occasions,

Advice #1.

But the law of reputations is like a bungee cord: you plunge down,

you bounce up, though to diminishing depths and heights each time.

In 1983, Sten Nadolny published The Discovery of Slowness, a novel

that gave us a thoughtful Franklin, not exactly a hero but an unusual

talent, and certainly no villain. Rehabilitation was on the way.

Then came Owen Beattie’s discoveries, and the description of

them in Frozen in Time. It was now clear that Franklin was no arrogant

idiot. Instead, he became a quintessentially twentieth-century

victim: a victim of bad packaging. The tins of food aboard his ships

had poisoned his men, weakening them and clouding their judgment.

Tins were quite new in 1845, and these tins were sloppily

sealed with lead, and the lead had leached into the food. But the

symptoms of lead poisoning were not recognized at the time, being

easily confused with those of scurvy. Franklin can hardly be blamed

for negligence, and Beattie’s revelations constituted exoneration of a

kind for Franklin.

There was exoneration of two other kinds, as well. By going where

Franklin’s men had gone, Beattie’s team was able to experience the

physical conditions faced by the surviving members of Franklin’s

crews. Even in summer, King William Island is one of the most

difficult and desolate places on earth. No one could have done what

these men were attempting—an overland expedition to safety.

Weakened and addled as they were, they didn’t have a hope. They

can’t be blamed for not making it.

The third exoneration was perhaps—from the point of view of

historical justice—the most important. After a painstaking, finger-numbing

search, Beattie’s team found human bones with knife

marks and skulls with no faces. John Rae and his Inuit witnesses, so

unjustly attacked for having said that the last members of the Franklin

crew had been practising cannibalism, had been right after all. A

large part of the Franklin mystery had now been solved.

Another mystery has since arisen: Why has Franklin become such

a Canadian icon? As Geiger and Beattie report, Canadians weren’t

much interested at first: Franklin was British, and the North was

far away, and Canadian audiences preferred oddities such as Tom

Thumb. But over the decades, Franklin has been adopted by Canadians

as one of their own. For example, there were the folk songs, such

as the traditional and often-sung “Ballad of Sir John Franklin”—a

song not much remembered in England—and Stan Rogers’s well-known

“Northwest Passage.” Then there were the contributions of

writers. Gwendolyn MacEwen’s radio drama, Terror and Erebus, was

first broadcast in the early 1960s; the poet Al Purdy was fascinated

by Franklin; the novelist and satirist Mordecai Richler considered

him an icon ripe for iconoclasm, and, in his novel Solomon Gursky

Was Here, added a stash of cross- dresser women’s clothing to the

contents of Franklin’s ships. What accounts for such appropriation?

Is it that we identify with well- meaning non- geniuses who get tragically

messed up by bad weather and evil food suppliers? Perhaps. Or

perhaps it’s because—as they say in china shops—if you break it, you

own it. Canada’s north broke Franklin, a fact that appears to have

conferred an ownership title of sorts.

It’s a pleasure to welcome Frozen in Time back to the bookshelves

in this revised and enlarged edition. I hesitate to call it a groundbreaking

book, as a pun might be suspected, but groundbreaking

it has been. It has contributed greatly to our knowledge of a signal

event in the history of northern journeying. It also stands as a tribute

to the enduring pull of the story—a story that has passed through all

the forms a story may take. The Franklin saga has been mystery, surmise,

rumour, legend, heroic adventure, and national iconography;

and here, in Frozen in Time, it becomes a detective story, all the more

gripping for being true."

Extracted from Burning Questions by Margaret Atwood, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Shot to Save the World by Gregory Zuckerman