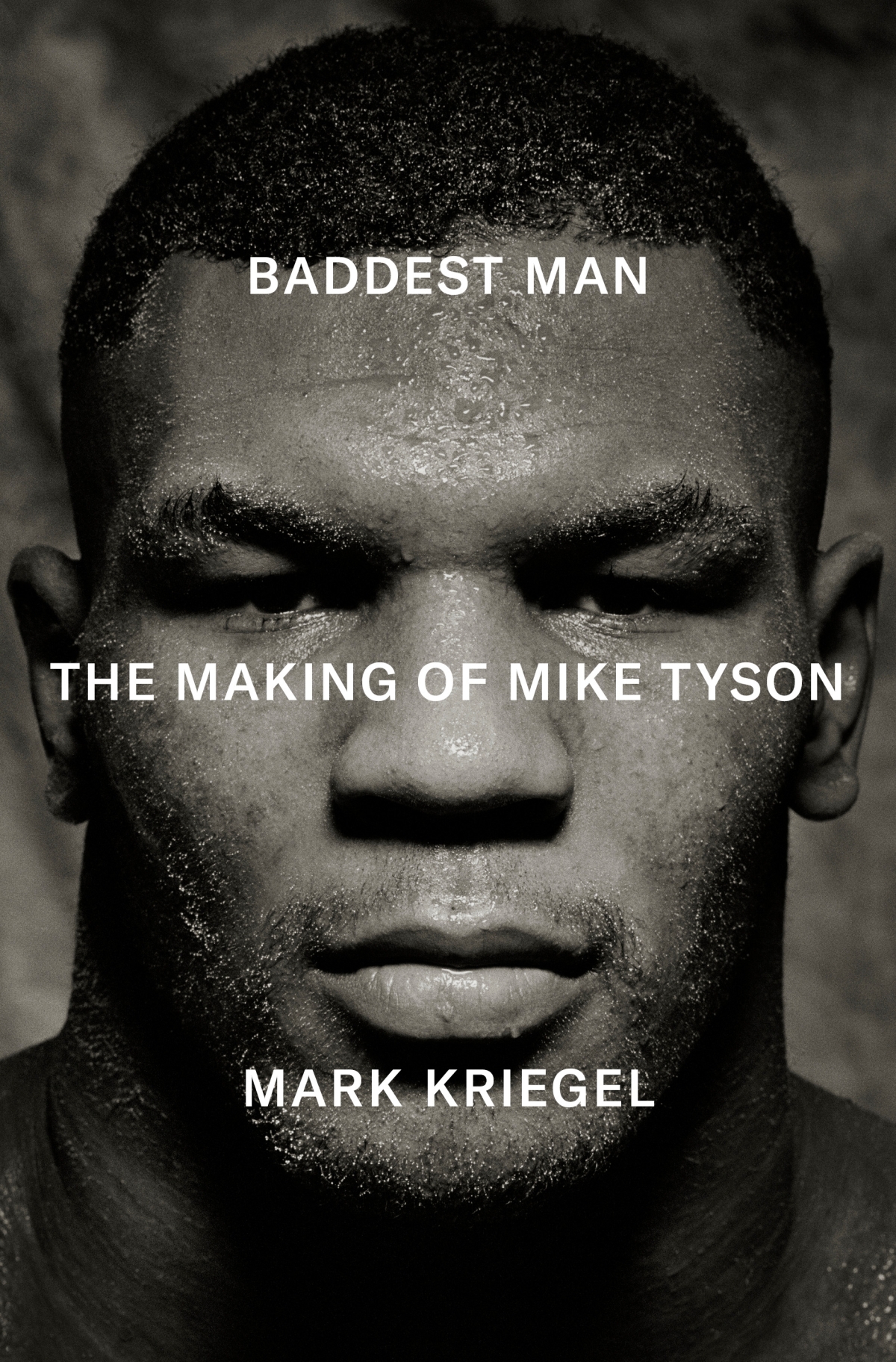

On a legendary 1980s night, 21-year-old Mike Tyson knocked out Michael

Spinks in 91 seconds, earning more than the Lakers and Celtics’ annual

payrolls combined. Just eight years earlier, Tyson was a troubled kid taken

in by boxing legend Cus D’Amato. Their bond became the stuff of movies,

turning Tyson into HBO’s first star. But his story is darker than his victories.

In Baddest Man, acclaimed biographer Mark Kriegel explores Tyson’s life

through what he survived, not who he defeated – capturing his cultural

impact and the deeper truths behind a feared and misunderstood icon.

Prologue

A copper‑skinned girl in tennis whites works diligently on her forehand, a teaching pro feeding her a basket of balls. There’s a beat to their ritual: a happy velvet thump. One’s gaze can’t help but be drawn to the solitary figure in the bleachers. He sits still as a sculpture.

It’s been so long he may have forgotten how his mere presence inevitably distorts the setting, how things rearrange themselves around him. As the scene is related to me by another young pro, an unmistakable aura emanates from the man in the bleachers. A shimmery gasoline haze, I imagine from the description. Or smoke? Maybe he lit a fatty? No, I’m assured. His was the practiced gaze of a tennis dad. It didn’t swivel with the ball but remained fixed on the girl’s determined stroke. She is the sixth of his seven surviving children. His stance – elbows on quads, clasped hands supporting that great Roman urn of a head – suggests a compact Thinker. But the elements apparent on closer inspection – that sad slice above the eye, a nose and mouth from which could be cast a mask of Melpomene, and the tattoo that emerges under the shadow of his baseball cap – might evoke a kind of gargoyle.

Of course. He was a monster, not just ours but his own, too. The tattoo was meant to acknowledge and signify exactly that, a surrender to his supposed fate. But in the years since, his attempt at mocking self‑disfigurement has become, of all things, a logo, the markings of his brand. Mike Tyson has reconstituted himself as an avatar of bro culture.

It’s the greatest comeback I’ve ever seen – not his booming, eponymous marijuana business or the fawning celebs who appear on his podcast, but the idea of him here, so at home in the land of wealth and whiteness, a grand duchy of eternal sunshine and good dentistry, elective surgeries and German cars.

Like most of the locals, he’s become an avid devotee of self‑care. His morning constitutionals take him on a trail overlooking the very edge of America, a vista that soars past equidistant palm trees to the aptly named Pacific. His mental‑hygiene regimen calls for periodic psychedelic trips on the venom of warted frogs. I don’t quite understand what it is that he claims to have seen during these journeys, God or Death. But I do know that psychic distance pales in comparison with the vastness he’s traveled to arrive here from the point of origin, the place that birthed his dirty shadow self, Brownsville, Brooklyn.

In 1988, the year of his first public crack‑up, I was a general‑assignment reporter at the New York Daily News and trying, without much success, to write a novel. It was about a kid – an ambitious thug who makes it big and tries to outrun his fate, which he finally meets with the aforementioned ocean at his back, by the Ferris wheel on the Santa Monica Pier. As my protagonist also hailed from Brownsville, I fancied myself retelling the story of Murder, Inc., as a parable of what would come to be known as the hip‑hop generation. Never mind that I didn’t yet have the skill to write such a book, or that today it would qualify as an act of cultural appropriation. Eventually, my agent broke the news (more gently than some of my colleagues) that the conception itself was a nonstarter. All perps weren’t created equal. Italian gangsters? He could sell that for sure. But Black kids from Brooklyn? They didn’t sell.

There was a name for those kids – that ilk, if you will – all of them inevitably lumped together, as if they constituted an urban phylum. You’d hear it in the police precincts, in the newsroom, and the bars where we’d retire after putting the paper to bed: Piece a shit.

They were chain snatchers, pickpockets, muggers, dope slingers, and vandals. They prowled the subways and Times Square, armed with box cutters or posing as bait for chicken hawks, and were typically alumni of the notorious Spofford Juvenile Detention Center, 1221 Spofford Avenue, Bronx, New York.

They were Tyson.

Before he was Tyson, of course.

“The monster transformed into a tennis dad with a goldendoodle, whose morning walks afford him an ocean view.”

He was a Grandmaster Flash lyric come to life. Tyson was “The Message.”

If Bernie Goetz had capped him on the 2 train, no one would’ve much cared. Actually, more likely there’d have been a smattering of applause.

And don’t let anyone tell you he was saved by the nice old white man. That, too, was a form of commerce, an existential bargain. The old man was a kind of wizard, half sage, half kook. He didn’t merely make the delinquent child his ward but inhabited his innermost thoughts, making the boy believe he was “a scourge from God.” In return, Tyson was to consecrate his reputation, allowing the old man to live forever.

“And did I not?” Tyson tells me. “As long as people know my name, they’re going to know his. My existence is his glory.”

Glory is a long shot in any boxing story. I cover fighters, and all but the rarest of them feel as though they were born to be destroyed. They tend to get used up – physically, neurologically, financially, and spiritually. I don’t know if it’s because they’re typically born into violence or because their craft itself is violence, albeit an artful form. Whatever the case, fighters who end up ruined seem the rule, not the exception.

Even as Tyson became boxing’s greatest‑ever attraction, his doom seemed a lock. In fact, before too long it was the very prospect of impending doom that became the attraction itself. At any juncture in his career, the smart bet on Tyson’s mortality was always the under.

I’ve written more than my share of nasty things about Tyson – many of them justified, some of them not, some of them shameful. But I’ve also learned it’s better to judge fighters not on their record but by what they’ve survived. And by that measure, the image of him watching his daughter smashing forehands, so steadfast in her task, grabs at my throat.

Tyson has withstood most of the urban plagues, those particular perils endemic to a time and a place. But also the death of a mother and the absence of a father.

Incarceration.

Molestation.

Booze.

Coke.

Boxing.

Don King.

The death of a child.

And perhaps most treacherous of all, fame. His wasn’t the kind that got you a good table at Elaine’s. Rather, it was a lethal dose of a peculiarly American disease, a form of insanity whose victims include Elvis, Marilyn, and Tupac.

But Tyson lives, ever defiant of the prophecy that foretold his early demise.

And that brings me, in a roundabout way, back to the kid I tried to invent in 1988. He would make it out of Brownsville (an impossibility, I was assured) only to die at the edge of America.

Compared with my stillborn novel, Tyson’s was the meanest of fairy tales, full of dungeons and wizards, archvillains, wicked witches and fairy godmothers. There would be lion tamers and movie stars, warriors and whores, pimps and spies. And still the erstwhile piece of shit – I mean that with unvarnished admiration – forges ahead. He is at once the victim and the victimizer, a convicted rapist beloved in the age of #MeToo, the monster transformed into a tennis dad with a goldendoodle, whose morning walks afford him an ocean view.

Tyson surpassed my capacity to imagine. Well, not just mine, but ours. His own, too. What follows began as a kind of essay – an attempt to explain the Tyson phenomenon – and became, perhaps inevitably, biography. There’s a distinct anatomy to his fame. For even among those with no recollection of his prime, the sheer idea of him, the planet’s Baddest Man, remains as potent as ever.

Which brings me back to my informant, the twentysomething tennis pro. He finds Tyson in the parking lot with his daughter. She’s almost twelve. At her age, Tyson was locked up. But this girl has the face of an Egyptian princess.

Is she beaming at him? Not sure. Let’s just say she has delighted eyes. “Dude,” says the awestruck pro.

Dude. Jesus.

Beneath the shade of his brimmed cap, Tyson’s squint dissolves into a grin.

“Dude. Much respect.”

Extracted from Baddest Man by Mark Kriegel, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Make Your Bed by William H McRaven