Ninety-one-year-old Gretel Fernsby has lived in the same mansion block in London for decades. She leads a comfortable, quiet life, despite her dark and disturbing past. She doesn't talk about her escape from Germany over seventy years before. She doesn't talk about the post-war years in France with her mother. Most of all, she doesn't talk about her father, the commandant of one of the most notorious Nazi concentration camps.

PART 1

The Devil’s Daughter

LONDON 2022 / PARIS 1946

1

If every man is guilty of all the good he did not do, as Voltaire suggested,

then I have spent a lifetime convincing myself that I am

innocent of all the bad. It has been a convenient way to endure decades

of self-imposed exile from the past, to see myself as a victim of

historical amnesia, acquitted from complicity, and exonerated from

blame.

My final story begins and ends, however, with something as trivial

as a box cutter. Mine had broken a few days earlier and, finding it a

useful tool to keep in a kitchen drawer, I paid a visit to my local hardware

shop to purchase a new one. Upon my return, a letter was

waiting for me from an estate agent, a similar one delivered to every

resident of Winterville Court, politely informing each of us that the

flat below my own was being put up for sale. The previous occupant,

Mr Richardson, had lived in Flat One for some thirty years but

died shortly before Christmas, leaving the dwelling empty. His

daughter, a speech therapist, resided in New York and, to the best of

my knowledge, had no plans to return to London, so I had made my

peace with the fact that it would not be long before I was forced to

interact with a stranger in the lobby, perhaps even having to feign an

interest in his or her life or be required to divulge small details about

my own.

Mr Richardson and I had enjoyed the perfect neighbourly relationship

in that we had not exchanged a single word since 2008. In

the early years of his residence, we’d been on good terms and he had

occasionally come upstairs for a game of chess with my late husband,

Edgar, but somehow, he and I had never moved past the

formalities. He always addressed me as ‘Mrs Fernsby’ while I referred

to him as ‘Mr Richardson’. The last time I set foot in his flat had been

four months after Edgar’s death, when he invited me for supper and,

having accepted the invitation, I found myself on the receiving end

of an amorous advance, which I declined. He took the rejection

badly and we became as near to strangers as two people who coexist

within a single building can be.

My Mayfair residence is listed as a flat but that is a little like

describing Windsor Castle as the Queen’s weekend bolthole. Each

apartment in our building – there are five in total, one on the ground

floor, then two on both floors above – is spread across fifteen hundred

square feet of prime London real estate, each with three

bedrooms, two and a half bathrooms, and views over Hyde Park

that value them, I am reliably informed, at somewhere between

L2 million and L3 million pounds apiece. Edgar came into a substantial

amount of money a few years after we married, an unexpected

bequest from a spinster aunt, and while he would have preferred to

move to a more peaceful area outside Central London, I had done

some research of my own and was determined not only to live in

Mayfair but to reside in this particular building, should it ever prove

possible. Financially, this had seemed unlikely but then, one day,

like a deus ex machina, Aunt Belinda passed away and everything

changed. I’d always planned on explaining to Edgar the reason why

I was so desperate to live here, but somehow never did, and I rather

regret that now.

My husband was very fond of children but I agreed only to one,

giving birth to our son, Caden, in 1961. In recent years, as the property

has increased in value, Caden has encouraged me to sell and

purchase something smaller in a less expensive part of town, but I

suspect this is because he worries that I might live to be a hundred

and he is keen to receive a portion of his inheritance while he is still

young enough to enjoy it. He is thrice married and now engaged for

a fourth time; I have given up on acquainting myself with the women

in his life. I find that as soon as one gets to know them, they are despatched,

a new model is installed, and one has to take the time to

learn their idiosyncrasies, as one might with a new washing machine

or television set. As a child, he treated his friends with similar ruthlessness.

We speak regularly on the telephone, and he visits me for

supper every two weeks, but we have a complicated relationship,

damaged in part by my year-long absence from his life when he was

nine years old. The truth is, I am simply not comfortable around

children and I find small boys particularly difficult.

My concern about my new neighbour was not that he or she

might cause unnecessary noise – these flats are very well insulated

and, even with a few weak spots here and there, I had grown accustomed

over the years to the various peculiar sounds that rose up

through Mr Richardson’s ceiling – but I resented the fact that my

ordered world might be upset. I hoped for someone who had no

interest in knowing anything about the woman who lived above

them. An elderly invalid, perhaps, who rarely left the house and was

visited each morning by a home-help.

A young professional who disappeared on Friday afternoons to her weekend home and returned

late on Sundays, spending the rest of her time at the office or the

gym. A rumour spread through the building that a well-known pop

musician whose career had peaked in the 1980s had looked at it as a

potential retirement home but, happily, nothing came of that.

My curtains twitched whenever the estate agent pulled up outside,

escorting a client in to inspect the flat, and I made notes about

each potential neighbour. There was a very promising husband and

wife in their early seventies, softly spoken, who held each other’s

hands and asked whether pets were permitted in the building

– I was listening on the stairwell – and seemed disappointed when told they

were not. A homosexual couple in their thirties who, judging by the

distressed condition of their clothing and their general unkempt air,

must have been fabulously wealthy, but who declared that the ‘space’

was probably a little small for them and they couldn’t relate to its

‘narrative’. A young woman with plain features who gave no clue as

to her intentions, other than to remark that someone named Steven

would adore the high ceilings. Naturally, I hoped for the gays – they

make good neighbours and there’s little chance of them procreating

but they proved to be the least interested.

And then, after a few weeks, the estate agent no longer brought

anyone to visit, the listing vanished from the Internet and I guessed

that a deal had been struck. Whether I liked it or not, I would one

day wake to find a removals van parked outside and someone, or a

collection of someones, inserting a key into the front door and taking

up residence beneath me.

Oh, how I dreaded it!

“Father had spoken with such confidence of the genetic superiority of our race and of the Führer’s incomparable skills as a military strategist that victory had always seemed assured.”

2

Mother and I escaped Germany in early 1946, only a few months

after the war ended, travelling by train from what was left of Berlin

to what was left of Paris. Fifteen years old and knowing little of life,

I was still coming to terms with the fact that the Axis had been

defeated. Father had spoken with such confidence of the genetic

superiority of our race and of the Führer’s incomparable skills as a

military strategist that victory had always seemed assured. And yet,

somehow, we had lost.

The journey of almost seven hundred miles across the continent

did little to encourage optimism for the future. The cities we passed

through were marked by the destruction of recent years while the

faces of the people I saw in the stations and carriages were not

cheered by the end of the war but scarred by its effects. There was a

sense of exhaustion everywhere, a growing realization that Europe

could not return to how it had been in 1938 but needed to be rebuilt

entirely, as did the spirits of its inhabitants.

The city of my birth had been almost entirely reduced to rubble

now, its spoils divided between four of our conquerors. For our protection,

we remained hidden in the basements of those few true

believers whose homes were still standing until we could be provided

with the false papers that would ensure our safe removal

from Germany. Our passports now bore the surname of Guéymard,

the pronunciation of which I practised repeatedly in order

to ensure that I sounded as authentic as possible, but while Mother

was now to be called Nathalie – my grandmother’s name – I

remained Gretel.

Every day, fresh details of what had taken place at the camps came

to light and Father’s name was becoming a byword for criminality of

the most heinous nature. While no one suggested that we were as

culpable as him, Mother believed that it would spell disaster for us to

reveal ourselves to the authorities. I agreed for, like her, I was frightened,

although it shocked me to think that anyone could consider

me complicit in the atrocities. It’s true that, since my tenth birthday,

I had been a member of the Jungmädelbund, but so had every other

young girl in Germany. It was mandatory, after all, just like being

part of the Deutsches Jungvolk was compulsory for ten-year-old

boys. But I had been far less interested in studying the ideology of

the Party than in taking part in the regular sporting activities with

my friends. And when we arrived at that other place, I had only gone

beyond the fence once, on that single day that Father had brought

me into the camp to observe his work. I tried to tell myself that I had

been a bystander, nothing more, and that my conscience was clear,

but already I was beginning to question my own involvement in the

events I had witnessed.

As our train entered France, however, I grew worried that our

accents might give us away. Surely, I reasoned, the recently liberated

citizens of Paris, shamed by their prompt capitulation in 1940, would

react aggressively towards anyone who spoke as we did? My concern

was proven correct when, despite demonstrating that we had more

than enough money for a lengthy stay, we were refused rooms at five

separate boarding houses; it was only when a woman in Place

Vendôme took pity on us and shared the address of a nearby lodging

where, she said, the landlady asked no questions that we found

somewhere to live. Had it not been for her, we might have ended up

the wealthiest indigents on the streets.

The room we rented was on the eastern part of Île de la Cité and

in those early days I preferred to remain close to home, confining

myself to walking the short distance from Pont de Sully to Pont

Neuf and back again in endless loops, anxious about venturing

across bridges into unknown terrain. Sometimes I thought of my

brother, who had longed to be an explorer, and of how much he

would have enjoyed deciphering those unfamiliar streets, but, at

such moments, I was always quick to dismiss his memory.

Mother and I had been living on the Île for two months before I

summoned the courage to make my way to le Jardin du Luxembourg,

where an abundance of greenery made me feel as if I had

stumbled upon Paradise. Such a contrast, I thought, to when we had

arrived at that other place and been struck by its barren, desolate

nature. Here, one inhaled the perfume of life; there, one choked on

the stench of death. I wandered as if in a daze from the Palais to the

Medici fountain, and from there towards the pool, only turning

away when I saw a coterie of small boys placing wooden boats in the

water, the light breeze taking their vessels across to their playmates

on the other side. Their laughter and excited conversation provided

an upsetting music after the muted distress with which I had become

familiar and I struggled to understand how a single continent could

play host to such extremes of beauty and ugliness.

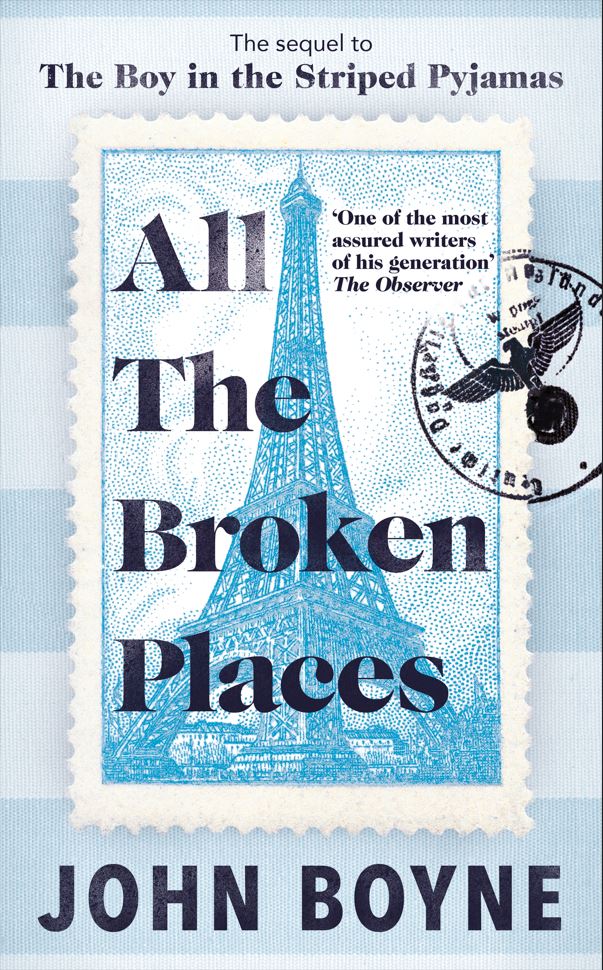

Extracted from All the Broken Places by John Boyne, out now.