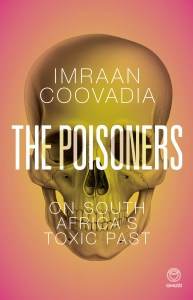

The Poisoners is a history of four devastating chapters in the making of the region, seen through the disturbing use of toxins and accusations of poisoning circulated by soldiers, spies, and politicians in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Author Imraan Coovadia chatted to The Penguin Post about the book, reality versus fiction and the evil that men do.

PP. Do you think the use of poison in South African/Zimbabwean politics is unique compared to other countries?

IC. Other societies have traditions of using poison for political killing: Russia comes to everybody's mind, but the United States has used chemicals on a very large scale for various military reasons. Then there are ancient uses of poison within religious and judicial practices. I think South Africa and Zimbabwe share a particular kind of distrustful, suspicious, and vigilant culture which is only intensified when you believe your neighbour, your party rival, or your wife or husband is likely to poison you.

PP. What interesting (albeit perhaps a bit bone chilling) facts about poison have you learnt in your research?

IC. When you have some idea of how many of the figures in this book have hidden or have even been celebrated by various structures and communities in our country – Wouter Basson appearing at the Kelvin Grove club or teaching Stellenbosch University students or working for Netcare as a cardiologist is only the best example – and you hear the paper-thin rationalisations given by these institutions, you realise that there is no kind of evil that South Africans won't embrace if it suits their prejudices. Also, for the most part, poisoners, given what they work with every day, get poisoned. Finally, the stories told about poisoning, especially by senior members of the government from Thabo Mbeki to Jacob Zuma and Ace Magashule, are in many ways more destructive than the individual killings.

PP. Are you not afraid to be on the receiving end, publishing a book like this?

IC. This is a very good question. In this book I tell the story of how Wouter Basson once made a dinner of prawns (a gift from Graça Machel) for Nelson Mandela and his guests. I say the guests might have been more nervous if they knew something about the cook.

PP. What is your personal poison?

IC. Dilmah Tea. It's very good.

PP. How did you find writing non-fiction, versus fiction?

IC. I wrote this book to understand for myself something about evil – what it is, what stories we tell about it, how it shapes our history. In fiction I would have my own imagination get in the way. In non-fiction, I could see what the facts were instead. In general, I find reality more convincing than fiction as I get older. It used to be the other way around.

The Poisoners is out now.

ALSO BY THIS AUTHOR

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY