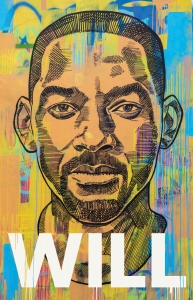

One of the most dynamic and globally recognized entertainment forces

of our time, Will Smith opens up fully about his life, in a brave and inspiring book that traces his learning curve to a place where outer success, inner happiness, and human connection are aligned. Along the way, Will tells

the story in full of one of the most amazing rides through the worlds of

music and film that anyone has ever had.

two

FANTASY

“NOW, I KNOW Y’ALL WERE THINKIN’ I was going to start this book off with, “Iiiiiin West Philadelphia, born and raised . . . ,” not with stories of domestic abuse and violence.

I was tempted, I mean, how could I not be? I’m a make-believer. And not just any ol’ make believer, I’m a Legendary, Bad Boy, Man in Black kind of make-believer: I’m a movie star. My first impulse is always to clean up the truth in my mind. To make it better. To shine it up a little bit so it doesn’t hurt as much. I redesign it and replace it with whatever suits me. Or really, whatever suits you: I’m a crowd-pleaser. It’s my actual job. The “truth” is whatever I decide to make you believe, and I will make you believe it: That’s what I do.

I’m a master storyteller. I thought about showing you the pretty me, a flawless diamond; a swaggy, unbreakable winner. A fantasy image of a successful human being. I’m always tempted to make- believe. I live in an ongoing war with reality.

Of course, there’s the red-carpet-walking, fly-car-driving, tight-fade-wearing, box-office-record-breaking, hot-chick-marrying, I Am Legend–pull-up-doing, jiggy-ass “Will Smith” . . .

And then there’s me. This book is about me.

Iiiiiin West Philadelphia, born and raised

On the playground is where I spent most of my days

Chilling out, maxing, relaxing all cool

I got my ass beat and bullied every day after school . . .

That’s how the song should have gone. OK . . . I can admit I was a weird kid. Kinda skinny, sorta goofy, with a bizarre taste in clothes. I was also the unfortunate owner of a prominent set of ears that made David Brandon once say that I looked like a trophy.

As I think back, I probably would have made fun of me, too. It didn’t help that I liked math and science; they were my favorite subjects in school. I think I like math because it’s exact; I like when things add up. Numbers don’t play games or have moods or opinions.

And I talked a lot — probably too much. But, most important, I had a wild and vivid imagination, a fantasy life that was much broader and lasted way longer than most children. Whereas when most kids just played around with plastic army men, Nerf balls, and toy guns, I would construct elaborate fantasy scenarios and then get lost in them.

When I was about eight or nine, Mom-Mom sent me and Pam to Sayre Morris day camp in Southwest Philadelphia. It was the usual, bargain-basement thing: rec room, swimming pool, arts and crafts. I came home after the first day and ran into the kitchen, where my mom was sitting with our next-door neighbor, Miss Freda.

“Hey, baby, how was camp?” Mom-Mom asked.

“Aw, Mom, I loved it. They had this big jazz band with trumpets and violins and singers and drums, and they had one of those horn things that do like this.” I mimicked the back-and-forth movement of a trombone.

“And then we had a dance battle, and like fifty people were doing choreographed moves together. . . .”

Miss Freda looked at my mom — A full jazz band? Fifty choreographed dancers? At a children’s summer camp?

What Miss Freda didn’t know was that she was caught in the cross fire of a playful game between my mother and me, one that still goes on even to this day. The rules are, I describe the most colorful, vivid, outlandish scene that I can come up with, which I then superimpose over the reality of my actual experience, and Mom-Mom’s job is to determine how much of it is actually true, and in which case, does she need to do something?

My mom paused and came nose to nose with me. Her gaze served as a sort of old-school, mother-wit lie detector, looking for the slightest wobble in my commitment to my story. I didn’t flinch.

She’d seen enough.

“Willard, stop playing. There was no jazz band at Sayre day camp.”

“No, Mom, I’m telling you — it was crazy.”

Miss Freda, confused, said, “But, Carolyn, he didn’t even know the word for a trombone — he had to have seen it, right?”

“No. He does this mess all the time.”

Just then, Pam walked into the kitchen, and my mother said, “Pam, was there a full jazz band, a dance contest, and a trombone at camp today?”

Pam rolled her eyes.

“What? No. It was a jukebox, Mom. Will stood there and listened to the jukebox all day — he didn’t even get in the pool.”

Mom-Mom looked to Miss Freda. “I told you.”

I burst into laughter — Mom-Mom won this round, but at least I beat Miss Freda.

“When I say silly stuff, it makes the world lighter for her. But she needs me to say smart stuff, too. That makes her feel safe.”

“My imagination is my gift, and when it merges with my work ethic, I can make money rain from the heavens.

My imagination has always been the part of me that Mom-Mom loved the most. (Well, that and when I got good grades.) It’s a weird mix of love that she has for me. She loves my silly side, but she needs me to be smart.

At some point in her life, she decided that she was only allowed to talk about important stuff: educational reform, generational wealth, the new misleading national health guidelines. She doesn’t “entertain foolishness.” Her and Daddio debated everything.

“Integration is the worst thing that ever happened to Black folks,” Daddio said emphatically.

“You don’t believe that, Will — you’re just sayin’ it to pluck my nerves,” Mom-Mom said dismissively.

“Listen to me, Car’lyn! Before integration, we had our own. Black businesses were thriving because niggas had to patronize niggas. The cleaners, the restaurant, the hardware store — everybody needed everybody. As soon as Black folks was allowed to eat at McDonald’s, our entire economic infrastructure collapsed.”

“So are you suggesting that you’d prefer to be raising these children in slavery, or in Jim Crow?” Mom-Mom said.

“I’m suggestin’ that if there was a nigga water fountain, niggas would be gettin’ hired to fix it.”

Mom-Mom would never say it to Daddio, but she would repeat all the time, “Never argue with a fool, because from a distance, people can’t tell who’s who.” So when she would stop arguing with you, you knew what she thought of your position.

When I say silly stuff, it makes the world lighter for her. But she needs me to say smart stuff, too. That makes her feel safe. She thinks that the only way I’ll be able to survive is if I’m intelligent. She likes about a sixty-forty ratio of smart to silly. She’s the best audience I’ve ever had. It’s like there’s some hidden part of her that even she’s not aware of that’s always egging me on.

Come on, Will, sillier, smarter, sillier, smarter . . .

I like to hit her with stuff that, on the surface, is super silly, and I hide the smart under it to see if she can find it. I like the look on her face when she thinks something is just stupid, and then the smart part sneaks up on her. (That’s my favorite, too.)

Comedy is an extension of intelligence. It’s hard to be really funny if you’re not really smart. And laughter is Mom-Mom’s medicine. In a way, I’m her little doctor, and the more she laughs, the more silly, smart, spectacular shit I make up.

“For me, the border between fantasy and reality has always been thin and transparent, and I’ve been able to step in and out of each effortlessly.”

“As a child, I would disappear into my imagination. I could daydream Endlessly — there was nothing more entertaining to me than my fantasy worlds. There was a jazz band at camp; I heard the trumpets; I saw the trombone, the zoot suits, the big dance scene. The worlds that my mind created and inhabited were as real to me as “real life,” sometimes even more so.

This constant stream of images and colors and ideas and silliness became my safe place. And then, to be able to share that space, to be able to transport someone, became the ultimate bliss. I love the ecstasy of a person’s rapt attention, taking them on a roller-coaster ride of their emotions locked in harmony with my fantasy creation.

For me, the border between fantasy and reality has always been thin and transparent, and I’ve been able to step in and out of each effortlessly.

The problem is one man’s fantasy is another man’s lie. I developed a reputation in the neighborhood as a compulsive liar. My friends felt like they could never trust what I said.

This is a strange quirk about me and even continues to this day. It’s a running joke among my friends and family that you have to dial back my stories two or three notches to know what actually happened. Sometimes I’ll tell a story and then a friend will look at Jada and say, “OK, so what really happened?”

But as a child, what the other kids didn’t understand was that I didn’t lie about my perceptions, my perceptions lied to me. I would get lost; sometimes I would lose track of what was real and what I had made up. It became a defense mechanism — my mind wouldn’t even contemplate what was true. I would think, What do they need to hear to be OK?

But Mom-Mom got me — she delighted in my peculiarities. She made space for me to be as silly and creative as I could be.

For instance, for much of my childhood I had an imaginary friend named Magicker. A lot of kids go through the imaginary-friend phase — usually between four and six years old. Those imaginary friends are amorphous identities that don’t really have any shape or personality. The imaginary friend wants whatever the child wants, hates what the child hates, and so on. It’s made up to affirm the child’s thoughts and feelings.

But Magicker was different; even as I write this book, the memory of Magicker is as vivid and resonant as any of the actual experiences of my childhood. He was a full-blown person.

Magicker was a little white boy with red hair, fair skin, and freckles. He always wore a little powder-blue polyester suit, with a fire-engine-red bow tie. His pants rode just a little bit too high, exposing poorly chosen white socks.

Whereas most other children’s imaginary friends served as projections and affirmations, Magicker had distinct preferences and opinions about what games we should play and where we should go and what we should do. Sometimes, he would disagree with me; other times, he’d make me go outside when I didn’t want to. He had strong ideas about certain types of foods and the character of people in my life. Even as I’m sitting here recalling our relationship, I’m thinking, Damn it, Magicker, this is my imagination!

Magicker was such a significant presence in my childhood that my mom would sometimes set out a separate plate for him at the dinner table. And if she wasn’t making any headway with me, she’d talk to Magicker instead.

“OK, Magicker, are you ready to go to bed?”

Fortunately, this was the one thing that Magicker and I always agreed on — we were never ready to go to bed.

“I was always a bit of an oddball. Things that felt normal to me could seem strange to others, and things that other people celebrated sometimes didn’t inspire me in the least.”

“A side effect of being lost in a fantasy life was that I had a lot of eccentric ideas about what was fly, fashionable, or funny. For example, I’m not sure how it developed, but I stumbled into an unfortunate but passionate cowboy-boot phase. Man, I loved cowboy boots; in fact, I refused to wear anything else on my feet. I’d wear them with sweatsuits; I’d wear them with jeans.

Hell, I even wore them with shorts.

Now, a Black kid in West Philly in cowboy boots might as well just put a bull’s- eye on his back. Kids would make fun of me and tease me mercilessly, but I didn’t understand why. “These boots are dope!” And the more they laughed, the deeper my commitment to cowboy boots grew.

I was always a bit of an oddball. Things that felt normal to me could seem strange to others, and things that other people celebrated sometimes didn’t inspire me in the least.

Back in the day, Huffy mountain bikes were on fire; every kid wanted one. And one Christmas, all my friends on my block got together and we agreed to ask our parents for Huffy bikes that year. The plan was we would all ride our matching bikes to Merion Park, a small park just far enough outside our neighborhood to feel like we were on an adventure.

Well, Christmas came, and Santa made good on ten brand-new, matching Huffys. Noon rolled around, and everybody was out front.

Everybody, that is, except me.

See, I didn’t ask for a Huffy. Huffys were for suckaz! And they were about to witness what a real bike looked like. Because while they had all asked for stock, standard, run-of-the-mill Huffy mountain bikes, I ain’t no sheep. I had asked for . . . a bright red Raleigh Chopper. Choppers were those low-rider bikes with a big wheel in the back and a tiny one up front, with the handlebars that stuck way up in the air, with the three-speed gear shift and an L-bucket dragster saddle, a.k.a. the banana seat. They were like the Harley-Davidson of kid’s bikes. You felt like you were on a motorcycle on that thing. It was the undisputed coolest bike on earth.

I couldn’t sleep the night before imagining my entrance. I had worked out my big reveal: I would wait for everybody to line up out front, ready to go, but I would come out from the back driveway, maintaining the element of surprise. I even planned and practiced what I was gonna say when they saw me on my Chopper. “Whaddup, suckaz, what y’all waiting for? Let’s go!” and then I’d just ride past them so they would have to catch up with me: Will Smith, the leader of the pack, the king of the neighborhood.

The moment arrived. I had been watching them from behind the curtains in my living room; I could tell they were all waiting and wondering, Where’s Will at? And just then I rolled out from the driveway, handlebars scraping the heavens, peddling smoothly in my cowboy boots — that Raleigh Chopper first gear was butter.

I was the man.

I float on by, all eyes on me. I throw the nod, then hit them with the line: “Whaddup, suckaz, what y’all waitin’ for? Let’s go!”

It was quiet for a few seconds. I figured I had ’em shook.

Then I was nearly knocked off my Chopper by the roar of laughter that emerged behind me. Teddy Allison literally laid on the ground laughing.

Through his tears he managed to say, “What the fuck is that jawn?”

I hit the brakes and turned to scan the rest of the crowd to see if Teddy was just bussin’, or if he was speaking for everybody.

“Nigga, are you in a biker gang?” said Danny Brandon. “You can’t even see over them handlebars!”

Michael Barr said quietly, “This what happens when you go to white schools.”

But it didn’t matter what they thought, because to me, I was hot. That’s one of the things about having an overactive imagination: I could make my mind believe anything. I was able to cultivate an almost delusional level of confidence.

And while this somewhat skewed perception of myself would often end in ridicule or getting my ass kicked when I was young, on many occasions throughout my life it served as a superpower. When you are unaware that you shouldn’t be able to do something, then you just do it. When my parents told me I couldn’t be a rapper because there were no careers in hip-h op, it didn’t deter me, because I knew parents just don’t understand. When television producers asked me if I could act, I said, “Of course,” even though I had never acted a day in my life — I thought, How hard can it be? When movie studios said they couldn’t cast me because African American leads don’t sell to international audiences, I wasn’t necessarily offended, I just couldn’t understand how a motherfucker that wrong could have this job. It wasn’t just the racism that bothered me, it was the stupidity. People would tell me how I was supposed to be, and it just didn’t make any sense. I felt like their rules didn’t apply to me.

Living in your own little world with your own rules can be an advantage sometimes, but you have to be careful. You can’t get too detached from reality. Because there are consequences.”

Extracted from Will by Will Smith, out now.

|

|

|

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Damon Galgut wins the 2021 Booker Prize for The Promise