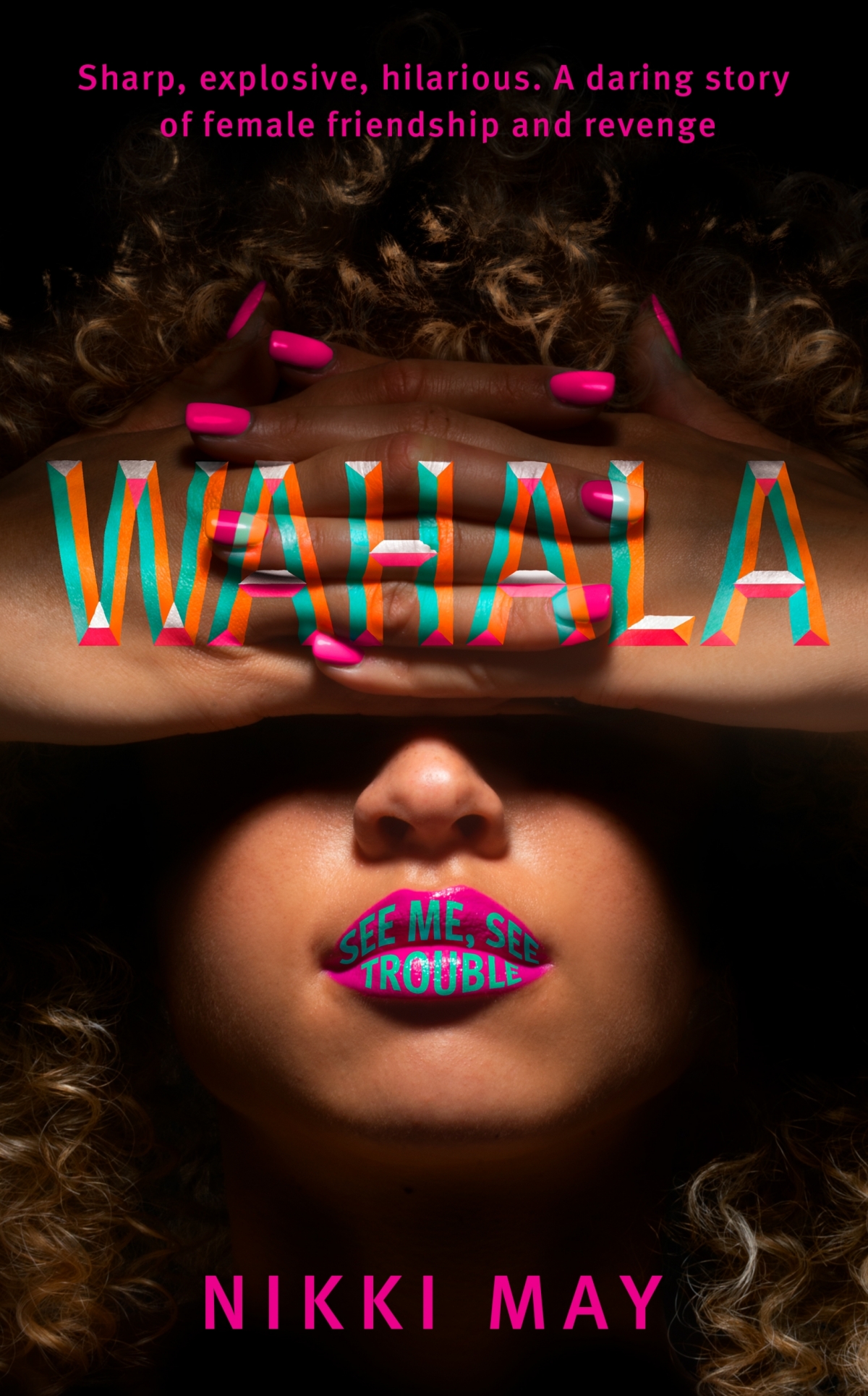

A darkly comic and bitingly subversive take on love, race and family, Wahala will have you laughing, crying and gasping in horror. Boldly political about class, colorism and clothes, here is a truly inclusive tale that will speak to anyone who has ever cherished friendship, in all its form.

Aftermath

Am I strong enough?

The woman sits huddled in the corner of her bedroom.

Her dress is ruined – the button missing, the belt ripped.

One seam has come apart, exposing her bare shoulder.

She’s clutching a sculpture in both hands. It’s a head, a

little under life-size. She stares into its unblinking eyes, willing

it to come to life. She wants it to tell her that this is not

her fault. That there’s nothing she could have done differently.

That she’s the victim here.

But it’s made of leaded brass. It can’t speak.

With trembling hands, she places it gently on the carpet.

Then, holding the split halves of her wrap dress together, she

clambers to her feet.

Am I strong enough?

She knows the answer. Justice must be done.

She picks up the phone.

‘Help me. Please . . .’

Four Months Earlier

1

Ronke

Pounded yam and egusi? Eba with okra? No, it had to be

pounded yam. But maybe with efo riro. Ronke ran through

the menu in her head as she walked up the hill to Buka. She

knew it by heart but that didn’t make choosing any easier. As

usual she wanted it all.

And as usual she was running late. She stopped at the

cashpoint anyway and withdrew a hundred pounds. The girls

teased her, told her it was an urban myth, but ever since

Ronke had heard the story about Simi’s cousin’s friend getting

her card cloned at Buka, she’d paid in cash.

Ronke had been looking forward to their Naija lunch all

week. And not just because of the food. For the first time in

ages, when Simi asked, ‘So what’s new?’, the answer wouldn’t

be, ‘Nothing.’

She hustled past the Sainsbury’s Local, the Turkish grocery

and the Thai nail bar. The Nigerian flag outside Buka

was looking a little tatty, frayed at the edges. The green was

still vibrant but the white was a dirty beige. Ronke studied

her reflection in the shiny mirrored door, yanked at her hair

to fluff up some of the curls, patted to flatten some down. As

good as it gets. At least once a day someone said to her, ‘I

wish I had curly hair,’ but Ronke knew better – curls meant

frizz, knots and chaos. She pushed open the door and stepped

out of suburban London and into downtown Lagos.

The smell hit her first. Smoky burned palm oil, fried peppers

and musty stockfish. Next came the noise: Fela Kuti

blared out of the speakers, struggling to compete with the

group of three men at a corner table, talking over each other.

And because this was effectively Nigeria, their voices were

louder, accents stronger, gesticulations wilder.

The waiter looked up with a scowl. As Ronke turned to

shut the door, she knew his eyes would linger on her arse.

It felt like home.

She spotted Simi deep in conversation with a striking

woman and felt a spike of irritation. ‘Just us two,’ Simi had

said. The stranger had long toned limbs and glossy brown

skin; she looked almost sculpted. Something about her profile

was familiar and for one heartbeat Ronke was sure she

knew her from somewhere. She blinked and the feeling disappeared.

She didn’t know anyone who showed side-boob at lunch. Or

had such an over-the-top blonde weave.

Ronke tried to tamp down her annoyance as she wove

between the tables towards them. The men stopped talking

and turned to watch her and she realized she was holding in

her tummy.

Simi stood and beamed at Ronke. It was easy to love Simi.

When she looked at you she made you believe you were the

only person in the world she wanted to see. Simi had given

Ronke the same grin the first time they met, seventeen years

ago, at freshers’ week in Bristol. Teeth, dimples, sunshine, joy.

‘Ronks! This is Isobel

– you’re going to love her.’ Simi

spread her arms out in welcome.

I wouldn’t bet on it, thought Ronke. She leaned into Simi’s

hug and fixed a smile on her face before turning to say hello

to the interloper. Still, three people meant three starters.

This Isobel had better be a sharer.

Simi poured her a glass of fizz as Ronke unwound her

scarf. ‘Champagne?’ Ronke asked. ‘We always have rosé

atBuka.’ It’s not forty pounds a bottle, she didn’t add.

Simi nudged Ronke with her knee under the table. ‘Iso’s

allergic to cheap wine,’ she said, ‘and we’re celebrating.’

‘Here’s to my divorce,’ said Isobel, holding her glass aloft,

‘and to friends – old and new.’

Ronke thought divorce was a strange thing to celebrate

but she smiled and clinked glasses.

“‘Isobel beat up a boy on our first day. After that we were inseparable.’”

The waiter plonked three massive menus on the table.

Pages and pages of laminated sheets nestled in faux leather

folders. Ronke adored the old-fashioned, over-long menu,

the notable absence of words like seasonal, local and sustainable,

the bad spelling and dodgy typography. She stroked

her menu and a rush of nostalgia flooded through her, echoes

of long family lunches at Apapa Club.

‘Wetin you people want?’ the waiter asked, glowering down

at them.

‘Another bottle of this.’ Isobel gestured at the empty champagne

bottle. The waiter’s frown deepened.

‘Thank you!’ called Ronke to his retreating back. She

tended to overcompensate with waiters. Even rude ones.

‘Isobel is embarrassingly rich,’ said Simi, ‘but she loves

throwing her money around, so I forgive her.’

Ronke laughed in spite of herself. ‘How do you two know

each other?’

‘We met when we were five,’ said Simi. ‘The only half-

Caste kids in our class . . .’

‘Simi! You can’t use that word,’ said Ronke.

‘Oh, come on, this is us. Everybody called us half-caste

In Lagos.’

‘You can’t even think it in LA, unless you want to be sent

on a race awareness course.’ Isobel stroked Simi’s arm. ‘It’s

so good to have my alobam back.’

‘We clocked each other straight away. You know how it is

when you spot another mixed-race person in Lagos.’ Simi

made exaggerated air quotes as she said ‘mixed-race’.

‘Isobel beat up a boy on our first day. After that we were

inseparable.’

‘He deserved it,’ said Isobel. ‘The little shit called you a

mongrel. It was only a little tap.’

‘You knocked two of his teeth out,’ said Simi.

‘He insulted us. Anyway, it worked.’ Isobel smiled. ‘No one

messed with us after that.’

Ronke tried and failed to place her accent. ‘Is your mum

American?’

‘Russian. My dad was working in Moscow, that’s where

they met.’ Isobel placed her hand on Ronke’s arm. Her nails

were electric blue, long and pointy. ‘What about you? I want

to know everything.’

Ronke fiddled with her scarf and glanced around for the

waiter. She hated talking about herself. ‘My mum’s English.

I was born in Lagos, but we moved here when I was eleven.

Have you looked at the menu?’

‘Ronke is the best dentist in London,’ Simi said. ‘And an

amazing cook.’

‘I’m not.’ Ronke wished Simi would stop jabbering like an

overexcited PR. ‘But I do love food. We should order

– they’re so slow here.’

Simi ignored her. ‘She’s practically perfect. Apart from her

dodgy taste in men.’

Ronke clenched her jaw and looked around for the waiter.

Isobel clapped her hands together and beamed. ‘Me too! I

knew we’d get on. I always go for the bad boy.’

‘Kayode isn’t a bad boy.’ Ronke glared at Simi and yanked

at a curl.

‘I love your hair,’ said Isobel. ‘How do you get it to spiral

like that? Is it real?’

Ronke gave Simi one more hard look, then turned to

Isobel. ‘Yes, it’s real.’

‘This isn’t.’ Isobel flicked her blonde mane from side to

side.

No kidding, thought Ronke. She didn’t want to be mollified.

‘Let’s order, I’m starving.’

‘Quick,’ Simi said. ‘If Ronke gets hangry, we’re in for it.

She’ll bitch-slap us with these tacky menus.’

Ronke patted her menu as she swallowed down another

twinge of annoyance. Hanger was a real thing; she’d read an

article about it in the Sunday Times just last week.

‘I’m not doing carbs – well, apart from wine,’ said Simi.

‘Fish pepper soup.’

‘No carbing in a Naija restaurant?’ Isobel’s laugh was high-

pitched and jangly. ‘You’re such a coconut. I’ll have amala

with ogbono and assorted meat.’

‘Jollof rice with chicken for me,’ said Ronke. She couldn’t

bring herself to order pounded yam in front of skinny, glamorous

Isobel. ‘Are we having starters?’ she added hopefully.

Isobel and Simi picked at their food – they were too busy

chatting about the good old days. Their Nigerian childhoods

had been filled with swimming pools, beach clubs, air-

conditioning, drivers and maids. Ronke’s memories were of

noisy family gatherings, power cuts, spicy street food, the car

breaking down and playing clapping games with her cousins

in the dusty courtyard.

Ronke listened as she ate. Simi was wearing a single oversized

earring, which made her look lopsided. Isobel on the

other hand was perfectly balanced – shoulders back, head

held high, blonde fringe perfectly straight.

Isobel pushed her plate away after three tiny bites. Don’t

stare, Ronke told herself, fighting the temptation to spear a

piece of shaki off her plate. Her jollof had been so-so

– she should have ordered the yam. Thank God she was getting a

takeaway.

The waiter dragged himself away from the TV and sauntered

over to clear their table. Ronke watched as he slammed

her empty plate on top of Isobel’s, squishing the black pillow

of amala. What a waste.

“This was the downside of telling your friends everything: it meant they knew everything. Yes, Kayode had left her standing like a saddo at St Pancras, watching the train pull out without them. Yes, she’d been in bits. But if Ronke could get over it, why couldn’t Simi?”

Isobel’s phone buzzed. ‘Got to go,’ she said. ‘My driver’s

here. I’ll get this – my treat.’ She went to the bar to pay the

bill, sashaying past the rowdy men.

One of them, eating eba and egusi with his hands in the

traditional way, paused, licked his fingers and called out to

her, ‘Hello, luscious yellow baby, why don’t you come and

greet us, ehn?’

Ronke froze. Simi tutted. But Isobel was unfazed; she

winked and put even more swagger into her walk as she came

back to the table. She bent to give Simi a hug, air-kissed

Ronke, and then she was gone, the door slamming behind

her.

‘Na wa, o!’ said Ronke.

‘That’s Iso,’ said Simi.

‘She has a driver? In London?’

‘Her dad’s loaded. I mean, proper rich. He was in the government

and in business. Legalized corruption – you know

the type. My dad used to be his lawyer, but they had a big

falling out. She’s been through hell so he’s being ultra-

protective.’

‘What sort of hell?’

‘A dodgy ex-husband. The controlling sort. He told her

what to wear, who to see, how to spend her own money.

Fucked her over. I’m guessing he was violent, but I didn’t

want to pry.’

‘That’s not like you,’ said Ronke.

Simi held her hands up in protest. ‘She was close to tears.

I couldn’t keep pushing her to talk.’

Ronke tried to imagine Isobel crying, but couldn’t. ‘But

she seems so confident, so self-assured, so . . . shiny.’

‘Ronks, you know how it is. We all have faces we put on. I

think her dad came to the rescue – saved her from him.

Hence Boris. The driver-cum-bodyguard.’

‘Boris? You are joking?’

‘OK, I made that up. But Boris suits him – he’s massive

and he’s Russian.’ Simi said the last bit in a terrible Russian

accent and they both burst into giggles.

‘I need to order a takeaway for Boo,’ said Ronke. ‘She’s

having a major strop with Didier. I’m going to hers after.

Come – it’ll be fun.’

‘I’ll pass. I had the oh-poor-me, I-do-everything spiel on

the phone this morning.’

Ronke managed to get the waiter’s attention and reeled off

her order. ‘Jollof rice with chicken stew, no chilli. Jollof rice

with fried beef. Pounded yam with seafood okra, extra hot,

please. Beef suya. Chicken suya. Two portions of dodo. One

moin-moin, please. Oh, and a Buka fish special.’

‘And one espresso.’ Simi gave him one of her high-

watt smiles. He almost smiled back, remembered himself

and went back to surly.

‘So what’s new?’ asked Simi. ‘How’s Kayode?’

‘My dodgy boyfriend?’ Ronke narrowed her eyes. ‘I can’t

believe you said that to someone I don’t know.’

‘Relax. Iso’s one of us. She gets it.’

‘Well, Kayode is fine. Tomorrow we’re going to look at a

flat in Clapham.’ Ronke had been waiting for this. She was

careful to keep her voice level, slipped it in as if it was idle

chit-chat.

Simi took the bait. ‘What? You’re flat-hunting? Together?’

Ronke wanted to stay deadpan but it was too exciting. ‘I

know. And it’s his idea. We spent hours on PrimeLocation

last night and he called the agent to book the viewing. I’m

seeing batik curtains, lots of raffia baskets, wooden floors

just like Boo’s – and a cot.’

‘A cot?’ said Simi.

‘Cat, I meant – cat.’ Ronke blushed. ‘But yes, I want kids.

You and Boo aren’t the only ones allowed happy ever after.’

‘Of course not. But come on, Ronks – we’re talking about

Kayode! He can’t even commit to a weekend in Paris.’

Ronke blinked at the peeling paint on the ceiling. This

was the downside of telling your friends everything: it meant

they knew everything. Yes, Kayode had left her standing like

a saddo at St Pancras, watching the train pull out without

them. Yes, she’d been in bits. But if Ronke could get over it,

why couldn’t Simi?

‘It wasn’t completely his fault,’ she said. ‘I know he didn’t

handle it well, but we’re fine now. Can’t you just pretend to

be pleased for me?’

‘I’m sorry. I just want you to be happy. Let’s start again.

Show me the flat.’ Simi shuffled her chair closer. ‘Please?’

Ronke tapped her phone with a short unpainted nail. ‘It

needs a lot of work, but that’s fine – good even. Like a blank

canvas. I can move into his flat while the builders fix it up. I

thought we could make it more open-plan.’

She jabbed at the phone, scrolling through the images.

‘It has a yard, south-facing; we can have loads of pots. It’s

at the top of our budget and we won’t get it, but . . .’

‘I love it,’ said Simi. ‘You can do a Kirsty, knock all the walls

down and fill it with scatter cushions.’

Ronke laughed. She did have a scatter cushion problem.

There were twenty-six in her little flat. Kayode had counted

once. All in similar shades of cream and silver. With tassels.

With sequins. With pompoms. And one extra special one

with tassels, sequins and pompoms. Kayode called her the

mad cushion lady, but in a nice way. He’d bought her the

extra special cushion. It was the only one that didn’t get

thrown on the floor at bedtime.

Simi chatted with her about houses and builders until

Ronke’s takeaway arrived. ‘Give Martin my love,’ said Ronke

as she wound her scarf round her neck. No lurid comments

from the loud men as they left. Simi hopped into her Uber

and Ronke, weighed down with her takeaway, headed for the

Tube. She hoped Boo would be a bit more positive about her

news.

Extracted from Wahala by Nikki May, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Glass House by Chinenye Emezi