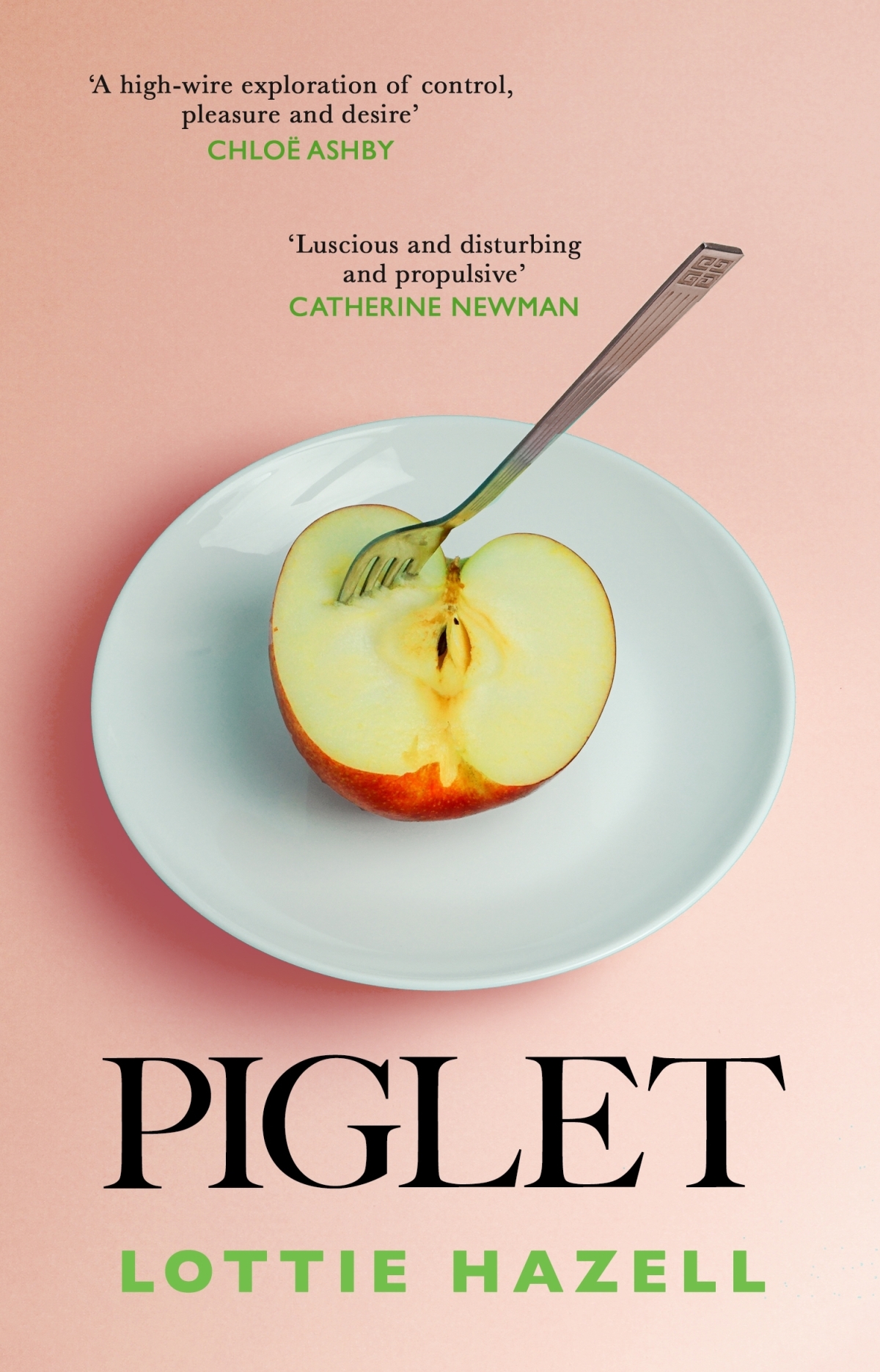

In this gripping debut, Piglet faces a façade-shattering revelation from her fiancé, Kit, just days before their wedding. As Piglet grapples with the dilemma, the narrative delves into themes of reinvention, domestic bliss, and the looming consequences of confronting uncomfortable truths. The story explores the dissonance between self-perception and societal expectations, questioning the cost of maintaining appearances. A stylish, uncommonly clever novel about the things we want and the things we think we want, Piglet is both an examination of women’s often complicated relationship with food and a celebration of the messes life sometimes makes for us. A captivating read.

98 Days

Piglet was sweating, and the supermarket chill was welcome on her breastbone, her back. Waitrose was full: shiny four-by-fours filling the car park, Saturday-morning shoppers with reusable bags jostling in the aisles.

Oxford was at the end of a heat wave, the novelty of sun-warmed skin worn, and the city was coated in the kind of grime that accumulated in weeks without rain. Outside, Piglet had watched from behind her sunglasses as a man and woman screamed at each other through their open car windows about a parking space.

Even in the cool sanctuary of the supermarket, the mood was irascible. A woman wearing Birkenstocks and ecru-coloured linen pushed past Piglet, reaching for a pecorino.

But guests would be arriving at six, and she didn’t have time to seethe among the cheeses. As she shopped, her fiancé, Kit, would be unpacking their house. Those words—still a novelty, like the stairs, the garden, the mortgage. Piglet stooped to pick up a block of feta and added it to her basket.

It had been her idea—a small housewarming supper for six—and he had been as excited as she was to show off their empty rooms, their white walls, their space. “We can invite Seb and Sophie,” he had said. “And Margot and Sasha,” she added. He had shrugged.

Texts had gone out, and boxes of saucepans, serving platters, and spices had been located, opened, and unpacked. Margot had replied immediately—“You’ve just moved in, shall we get pizza?”—but Piglet had insisted: “I’ll cook.”

She picked up salted butter, thick Greek yoghurt, and cream.

The menu was not modest. Her basket was already heavy with Charlotte potatoes, fresh herbs, and a Duchy chicken.

“There would be cold wine and open windows, patio doors thrown wide. It would all look and taste exquisite.”

It was too hot for a roast chicken, but Piglet had once heard Nigella say something about a house only being home once a chicken was in the oven. And anyway, there would be salads: one chopped and scattered with feta and sumac, another leafy with soft herbs. New potatoes, boiled and dotted with a bright salsa verde. Bread and two types of butter: confit garlic, and Parmesan and black pepper. There would be cold wine and open windows, patio doors thrown wide. It would all look and taste exquisite.

There had been roast chickens back in Derby, but her mother’s were always anaemic, trussed at the legs and moistened only by a gravy that had started life as a spoonful of granules. For dessert—or afters, as her father would say—there would be an apple pie from the Morrisons bakery or a roulade from the frozen aisle, depending on the season, eaten on the sofa in front of the television. Between bites, Piglet’s family—her parents, her sister, herself—would call out the answers to quiz shows, spoons scraping in their bowls. Piglet knew her parents still ate her mother’s roast chicken every Sunday. On Saturday it was a takeaway—Chinese, from the shop in town—and on Friday it was fish. No matter the weather, no matter the time of year. These routines, which had once cradled their familial bonds, their Sunday traditions, now made Piglet feel a crawling embarrassment, a creeping pity. She had learned since she left Derby, left her parents, that the only way to serve a dessert from the frozen aisle was ironically.

Extracted from Piglet by Lottie Hazell, out now.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK FROM THE AUTHOR >>

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY