Buckle up for a tour of South Africa – your guide the inimitable Sihle Khumalo. Born in South Africa, and having lived here for almost fifty years, Khumalo reflects on the past and ponders the future of this captivating yet complex country. He delves into the history of the names given to our towns and cities (from Graaff-Reinet to Schweizer-Reneke to Zastron) and in the process raises issues we might not have interrogated fully.

Phala Phala, the poem

Phala Phala was on the news.

Phala Phala farm was on Phalaphala fm.

What really happened?

Who would have thought?

Where did the money come from?

Why, oh, why?

How can he really explain this?

Phala Phala was on the news.

Phala Phala was the news.

It was shocking news.

It was good news.

It was great news, for some.

It was awful news, for others.

It was awesome news, for some.

The money was under the mattress.

The money was in the mattress.

The money was on the mattress.

The money was in the cupboard.

The mattress was in the money.

The money was in the mattress in the cupboard.

The money was in the cupboard under the mattress.

The money was in the mattress on a cupboard.

The money was on the cupboard under the mattress.

The money was on the mattress on the cupboard.

Oh, his audacity …

The audacity of the people

who strategised to protect him,

The audacity of the people

who protected him in parliament,

The audacity of South Africans

who keep voting for the same protection scheme.

Kuthi angiphalaze …

I feel like throwing up …

Dedicated to the late Chris van Wyk, who wrote ‘In Detention’.

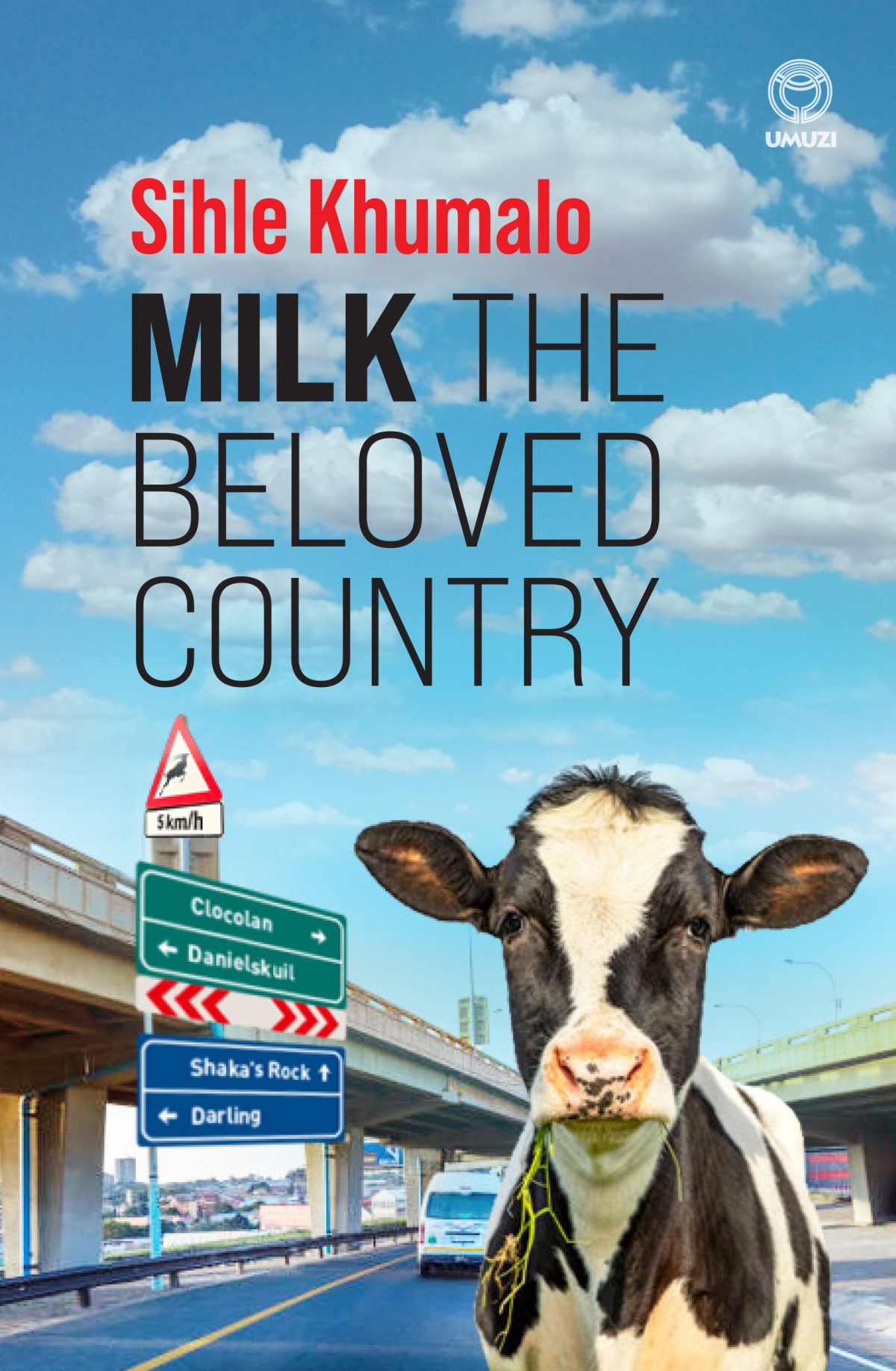

South Africa: the country that keeps giving – without fail – only to a select few. If South Africa was a cow, it would have a humungous udder which – against all thuggery and theft – never runs out of the goodies that keep the greedy coming back for more, and more. Maybe this explains why some politicians call our country a ‘cowntry’. The suckers are milking the country almost dry, but it keeps giving. Until when?

While traversing my own country in 2016, one of the things that struck me was that there is rich history behind the names of certain cities, towns, streets and so on. That 2016 adventure, covering all nine provinces, culminated in my book Rainbow Nation My Zulu Arse (Umuzi, 2018). There was still so much I wanted to say about my homeland, however – so here I am, back again, for another bite at this very rich yet very poor country called the Republic of South Africa – my country, our cowntry.

For starters, as a country we do not even have a name. What we have is a geographic location masquerading as a name. Modern-day Namibia, while colonised, was South West Africa, which is also a geographic location; Kenya was part of so-called British East Africa; and modern-day Burkina Faso was ‘Upper Volta’ (basically, the upper part of the Volta River). We, meanwhile, occupy a piece of land on the southern tip of the African continent, and that coincidentally happens to be, ahem, the name of our country.

Therefore, if you ask me, obsessing about name changes of cities, towns and streets when we as a country have no meaningful name not only entirely misses the bigger picture but also suggests that we lack the context and foundation on which all the other names should be based. And that could explain why, as has been witnessed, whenever the government attempts to change the names of cities, towns or streets, it becomes a highly emotional issue, and at times legal battles ensue.

*

The issue of old and new names is not the only topical issue in Mzansi, of course. In fact, our country is complex and, as such, trying to deal with its challenges means, among other things, that you have to cover a whole lot of themes and subjects. So the various parts of this book might feel totally different from each other, because that is exactly how our country is, in its true sense. You cross the road from Sandton to Alexandra, or vice versa, and it looks and feels as if you are in a different country altogether. Within half an hour of leaving the informal settlements of Khayelitsha, you are in the picturesque multimillion-rand wine farms of Stellenbosch. You read about multibillion-rand deals, and in the same newspaper there is a story about how the substantial part of the population lives below the poverty line.

“Whenever I see a politician, part of me knows that I am looking at an actor or an actress. Otherwise, how do you explain that some of them, if not all, publicly act as if they care about the poor, when they do not only not give a fuck about them, but also exploit them?”

We are a complex country partly because our past is complex and convoluted. We are the only country in sub-Saharan Africa that had two waves of independence: in 1910 we became a self-governing state of the British Empire called the Union of South Africa, and in 1961 we became a fully sovereign state called the Republic of South Africa. In both these instances, the minority of the population continued in power, and this was so for more than eight decades. This, therefore, means there was a third wave of independence: freedom for all, in 1994.

We, as people of this land, are not a product of just one thing or another. We are a product of everything. And more. Even victors are victims, to an extent. You might have your riches but you have no peace of mind. You have to constantly and consistently watch your back. Just in case.

Victims, on the other hand, can claim victories of some sort – that first person in the family to get a university degree or buy a car or buy property in the suburbs, for example. These are often highlighted as a case of the triumph of the human spirit. But, in essence, it is, I strongly feel, victims of the system claiming some sort of victory.

*

This is the story of South Africa. It is a country steeped in a colonial past, and shaped and moulded by the apartheid project. And it is a country in which, besides the rhetoric and cosmetic changes where young black people are being indoctrinated to be tenderpreneurs while the adult black population has internalised playing small in a white economic space through black economic empowerment (bee) deals and ineffective affirmative-action policies, darkies by and large remain in the economic and social darkness.

Of course, all of us have had an electoral voice since 1994. Some of the duly elected leaders have spent so much time, effort and energy enriching themselves (and their friends, families, mistresses, boyfriends and partners) that some among us have started missing certain things that used to work properly during the apartheid years.

You know that the government, which is predominantly black and is predominantly voted into power by black people, has failed when some black people start thinking – and even hoping – that white people will run the country again. Whenever I see a politician, part of me knows that I am looking at an actor or an actress. Otherwise, how do you explain that some of them, if not all, publicly act as if they care about the poor, when they do not only not give a fuck about them, but also exploit them?

*

The final part of this book is about reflection. I am not just reflecting on certain key episodes in our country’s story, I am at the same time questioning things that, to an extent, have not received the contemplation and deliberation they deserved. This lack of comprehensive analysis of our country can be attributed, I think, to the fact that there is so much happening not only politically but also socially, technologically and economically, that we as a people hardly have time to pause and reflect on historic events. And as such we, as some among us often say, ‘just carry on’.

But I am saying, ‘Hang on! Not so fast! Before we carry on …’ I am asking questions that in our busyness and in our quest to make a living we seem to have skimmed over. I am saying, let us have this maybe uncomfortable conversation with the openness and frankness that it deserves. This is a book in which I ask, among other things, is South Africa already a failed state and when was the state captured? It is a book that seeks to make you, dear reader, ponder and pause while not only asking yourself, ‘How did we get here?’ but also thinking what the future might hold. We need to think deeply about our country, and change course before it is too late.

Extracted from Milk the Beloved Country by Sihle Khumalo, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Land Matters by Tembeka Ngcukaitobi