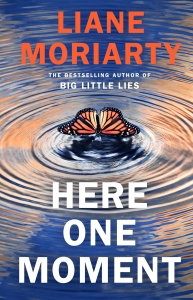

In this anticipated new novel from the bestselling author behind

Big Little Lies, a diverse group of strangers are each absorbed

in their own lives – a flight attendant working on her birthday, a

young man returning from a funeral, an ER nurse contemplating

retirement. But when an elderly woman crosses their paths with

a cryptic prediction, their carefully planned lives begin to unravel

in unexpected ways. Thought-provoking and gripping, this novel

explores how a single encounter can change everything.

1

Later, not a single person will recall seeing the lady board the flight at Hobart Airport.

Nothing about her appearance or demeanour raises a red flag or even an eyebrow.

She is not drunk or belligerent or famous.

She is not injured, like the bespectacled hipster with his arm scaffolded in white gauze so that one hand is permanently pressed to his heart, as if he’s professing his love or honesty.

She is not frazzled, like the sweaty young mother trying to keep a grip on a slippery baby, a furious toddler and far too much carry-on.

She is not frail, like the stooped elderly couple wearing multiple heavy layers as if they’re off to join Captain Scott’s Antarctic expedition.

She is not grumpy, like the various middle-aged people with various middle-aged things on their minds, or the flight’s only unaccompanied minor: a six-year-old forced to miss his friend’s laser-tag party because his parents’ shared custody agreement requires him to be on this flight to Sydney every Friday afternoon.

She is not chatty, like the couple so eager to share details of their holiday you can’t help but wonder if they’re working undercover for a Tasmanian state government tourism initiative.

She is not extremely pregnant like the extremely pregnant woman.

She is not extremely tall like the extremely tall guy.

She is not quivery from fear of flying or espresso or amphetamines (let’s hope not) like the jittery teen wearing an oversized hoodie over very short shorts which makes it look like she’s not wearing any pants, and someone says she’s that singer dating that actor, but someone else says no, that’s not her, I know who you mean, but that’s not her.

She is not shiny-eyed like the shiny-eyed honeymooners flying to Sydney still in their lavish bridal clothes, those crazy kids, leaving ripples of goodwill in their wake, and even eliciting a reckless offer from a couple to give up their business class seats, which the bride and groom politely but firmly refuse, much to the couple’s relief.

The lady is not anything that anyone will later recall.

The flight is delayed. Only by half an hour. There are scowls and sighs, but for the most part passengers are willing to accept this inconvenience. That’s flying these days.

At least it’s not cancelled. ‘Yet,’ say the pessimists.

The PA crackles an announcement: passengers requiring special assistance are invited to board.

‘Told you so!’ The optimists jump to their feet and sling bags over their shoulders.

While boarding, the lady does not stop to tap the side of the plane once, twice, three times for luck, or to flirt with a flight attendant, or to swipe frantically at her phone screen because her boarding pass has mysteriously vanished, it was there just a minute ago, why does it always do that?

The lady is not useful, like the passengers who help parents and spouses find vanished boarding passes, or the square-shouldered, square-jawed man with a grey buzz cut who effortlessly helps hoist bags into overhead lockers as he walks down the aisle of the plane without breaking his stride.

Once all passengers are boarded, seated and buckled, the pilot introduces himself and explains there is a ‘minor mechanical issue we need to resolve’ and ‘passengers will appreciate that safety is paramount’. The cabin crew, he points out, with just the hint of a smile in his deep, trustworthy voice, is also only hearing about this now. (So leave them be.) He thanks ‘folks’ for their patience and asks them to sit back and relax, they should be on their way in the next fifteen minutes.

They are not on their way in fifteen minutes.

The plane sits on the tarmac without moving for ninety-two horrendous minutes. This is just a little longer than the expected flight time.

Eventually the optimists stop saying, ‘I’m sure we’ll still make it!’

Everyone is displeased: optimists and pessimists alike.

During this time, the lady does not press her call button to tell a flight attendant about her connection or dinner reservation or migraine or dislike of confined spaces or her very busy adult daughter with three children who is already on her way to the airport in Sydney to pick her up, and what is she meant to do now?

She does not throw back her head and howl for twenty excruciating minutes, like the baby, who is really just manifesting everyone’s feelings.

She does not request the baby be made to stop crying, like the three passengers who all seem to have reached middle age with the belief that babies stop crying on request.

She does not politely ask if she may please get off the plane now, like the unaccompanied minor, who reaches his limit forty minutes into the delay and thinks that maybe the laser-tag party is a possibility after all.

She does not demand she be allowed to disembark, along with her checked baggage, like the woman in a leopard-print jumpsuit who has places she needs to be, who is never flying this airline again, but who finally allows herself to be placated, and then self-medicates so effectively she falls deeply asleep.

“No-one will remember hearing the lady speak a single word during the delay.”

She does not abruptly cry out in despair, ‘Oh, can’t someone do something?’ like the red-faced, frizzy-haired woman sitting two rows behind the crying baby. It isn’t clear if she wants something done about the delay or the crying baby or the state of the planet, but it is at this point that the square-jawed man leaves his seat to present the baby with an enormous set of jangly keys. The man first demonstrates how pressing a particular button on one key will cause a red light to flash and the baby is stunned into delighted silence, to the teary-eyed relief of the mother, and everyone else.

At no stage does the lady make a bitter-voiced performative phone call to tell someone that she is ‘stuck on a plane’ ‘still here’ ‘no way we’ll make our connection’ ‘just go ahead without me’ ‘we’ll need to reschedule’ ‘I’ll have to cancel’ ‘nothing I can do’ ‘I know! It’s unbelievable.’

No-one will remember hearing the lady speak a single word during the delay.

Not like the elegantly dressed man who says, ‘No, no, sweetheart, it will be tight, but I’m sure I’ll still make it,’ but you can tell by the anguished way he taps his phone against his forehead that he’s not going to make it, there’s no way.

Not like the two twenty-something friends who had been drinking prosecco at the airport bar on empty stomachs, and as a result multiple passengers in their vicinity learn the intimate details of their complex feelings about ‘Poppy’: a mutual friend who is not as nice as she would have everyone believe.

Not like the two thirty-something men who are strangers to each other but strike up a remarkably audible and extraordinarily dull conversation about protein shakes.

The lady is travelling alone.

She has no family members to aggravate her with their very existence, like the family of four who sit in gendered pairs: mother and young daughter, father and young son, all smouldering with rage over a fraught issue involving a phone charger.

The lady has an aisle seat, 4D. She is lucky: it is a relatively full flight but she has scored an empty middle seat between her and the man in the window seat. A number of passengers in economy will later recall noting that empty middle seat with envy, but they will not remember noting the lady. When they are finally cleared for take-off, the lady does not need to be asked to please place her seat in the upright position or to please push her bag under the seat in front of her.

She does not applaud with slow sarcastic claps when the plane finally begins to taxi towards the runway.

During the flight, the lady does not cut her toenails or floss her teeth.

She does not slap a flight attendant.

She does not shout racist abuse.

She does not sing, babble or slur her words.

She does not casually light up a cigarette as if it were 1974.

She does not perform a sex act on another passenger.

She does not strip.

She does not weep.

She does not vomit.

She does not attempt to open the emergency door midway through the flight.

She does not lose consciousness.

She does not die.

(The airline industry has discovered from painful experience that all these things are possible.)

One thing is clear: the lady is a lady. Not a single person will later describe her as a ‘woman’ or a ‘female’. Obviously no-one will describe her as a ‘girl’.

There is uncertainty about her age. Possibly early sixties? Maybe in her fifties. Definitely in her seventies. Early eighties? As old as your mother. As old as your daughter. As old as your auntie. Your boss. Your university lecturer. The unaccompanied minor will describe her as a ‘very old lady’. The elderly couple will describe her as a ‘middle-aged lady’.

Maybe it’s her grey hair that places her so squarely in the category of ‘lady’. It is the soft silver of an expensive kitten. Shoulder-length. Nicely styled. Good hair. ‘Good grey.’ The sort of grey that makes you consider going grey yourself! One day. Not yet.

The lady is small and petite but not so small and petite as to require solicitousness. She does not attract benevolent smiles or offers of assistance. Looking at her does not make you think of how much you miss your grandmother. Looking at her does not make you think anything at all. You could not guess her profession, personality or star sign. You could not be bothered.

You wouldn’t say she was invisible, as such.

Maybe semi-transparent.

The lady is not strikingly beautiful or unfortunately ugly. She wears a pretty green and white patterned collared blouse tucked in at the waistband of slim-fitting grey pants. Her shoes are flat and sensible. She is not unusually pierced or bejewelled or tattooed. She has small silver studs in her ears and a silver brooch pinned to the collar of her shirt, which she often touches, as if to check that it is still there.

Which is all to say, the lady who will later become known as ‘the Death Lady’ on the delayed 3.20 pm flight from Hobart to Sydney is not worthy of a second glance, not by anyone, not a single crew member, not a single passenger, not until she does what she does.

Even then it takes longer than you might expect for the first person to shout, for someone to begin filming, for call buttons to start lighting up and dinging all over the cabin like a pinball machine.

Extracted from Here One Moment by Liane Moriarty, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: By Any Other Name by Jodi Picoult