Two famous footballers stand trial for sexual assault, with

incriminating texts as evidence. As the trial progresses, Evan

Keogh reflects on his life since leaving his island home. Living

a lie, he is a talented footballer who aspired to be an artist and

a gay man in a sport intolerant of diversity. His knowledge of

the events of that night threatens more than his freedom or

career. While the jury decides his fate, Evan must determine

if he has become the man he wanted to be.

I dreamed that I dreamed about the musty grey soil of the island and the sweet perfume it emits after rainfall, a double remove from a place I will never visit again. My mother explained to me once that the fragrance comes from a combination of chemicals and bacteria in the earth which form filaments when wet, sending spores of aromatic vapour into the air. We find the scent comforting, she told me, because we want to believe there’ll be a welcoming place for us one day, when we’re buried deep inside it. I’ve been awake for almost an hour when my phone lights up with a message. I ignore it until another arrives a few moments later. Lifting it from its charger, I see that it’s from Robbie, as I knew it would be. I read the first one:

Counting on you today, bro. Don’t let me down.

And then the second:

Delete that, yeah?

I wonder how he can be so stupid as to text me at all. Messages like this have contributed to the trouble we’re in. The WhatsApp group chat where he had to brag about that night, and the replies, all made public, that made us look like a bunch of animals. He thinks that boasting is proof of our innocence, that if we’d actually committed a crime, then the last thing either of us would have done is brag about it. That might be true, but doesn’t he know that deleting them means nothing? Everything is saved in the phone’s internal hardware, or in the cloud, or on some anonymous server in a vast warehouse located under the Mojave Desert.

Nothing disappears. Nothing is forgotten. Everything we say or do these days clings to us for ever.

I climb out of bed and place my feet on the carpet. These feet that can do things that other boys’ feet cannot. Run down a pitch, evading human obstacles, with the grace of Rudolf Nureyev. Pick up a ball and bounce it effortlessly on strong toes. Curve it from the corner spot in a perfect arc, landing on the head of a chosen forward, or send it soaring over the leaping bodies of crotch-guarding defenders into the top-right corner of a net. How many times have they carried me to the side lines, where I drop to my knees before our army of fans, arms outstretched, pretending that I care about the adulation coming my way? They’ve been able to do this from as far back as I can recall, in the same way that some children are able to draw, or sing, or do impressions. Unfortunately, whatever magic I was granted found its way to the wrong limbs, for I did not want to be a footballer. I wanted to be a painter, but my eyes and hands did not have the gifts granted to my feet.

I walk over to the curtains and pull them apart, looking down towards the residents’ parking spaces below. My bright yellow Audi R8 glistens in the sunshine. I spent a fortune on it a year ago, eight weeks’ wages at the time, I calculated, and I only ever drive it to the training ground and back. It would have been cheaper to use taxis.

The fourteen-storey building I live in is located on the outskirts of the city, near the river. Each floor contains only a single apartment of 2,500 square feet and I live on the twelfth. Facing it, on the other side of a perfectly manicured circle of flowerbeds with a fountain at its centre, stands an identical building, where Robbie lives in a penthouse duplex. On the floors below me live two well-known actors, a moderately successful popstar and a former Home Secretary. In Robbie’s, there are three other footballers and a disgraced tennis coach. Our homes have more space than any of us need. There are home pods in every room and, if I want to hear a song, I say its name out loud and it plays. My voice controls the temperature, the water flow, the underfloor heating. There are six televisions, one in the living room, one in each of the three bedrooms, one in the kitchen and one facing the bath. I’d have preferred something simpler, but the club insisted, because they like to send the glossies over occasionally to photograph us relaxing with our girlfriends and this is the kind of place that the fans expect. Not that I have a girlfriend. Although they arranged one for me a few weeks after I moved in, when Hello! came to call. She seemed friendly enough, even suggested going for drinks afterwards, but I said no, blaming the following morning’s training session.

‘I’m not looking for anything,’ she told me. ‘It’s just a drink. I’ve been living with a woman for the last three years.’

I still said no.

‘Then I guess we’re breaking up,’ she said, kissing me on the cheek as she left. ‘It’s been fun, Evan.’

“Maybe if I wear them long enough, I can cause

some permanent damage and be set free.”

As I head towards the en suite, my phone rings and I sigh, assuming it’s Robbie again, but no, when I look at the screen, I see that it’s Dad calling. He and Mam arrived four days ago and are staying in a hotel in the city centre. I wish they hadn’t come over at all, but there was nothing I could do to keep them away. I consider rejecting the call, but I know what he’s like. He’ll keep phoning until I answer.

‘Hi,’ I say, lifting it to my ear.

‘You’re up, then.’

‘Of course I’m up.’

I can hear him breathing heavily. This life, this terrible life that I have, was his dream, not mine. I’ve become everything he wanted me to be since I left the island four years ago, but he’s still controlling me.

‘Watch your tone,’ he says quietly, and my nostrils fill with the smell of the loam, as they always do when I’m frightened or when I remember what I did that made me run away in the first place.

‘Sorry,’ I say.

‘You’re getting a taxi?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did the club organize it?’

‘No. They can’t get involved.’

‘Do you want me to have a word with them?’

I stifle a laugh. He actually thinks the club would listen to him. Its owner, directors and assets are worth somewhere between three and four hundred million pounds.

He might be a big man on the island with his farm and his third share of a grocery store and his fifth share of a boat, but he’s nothing here. He wouldn’t even get through the front door.

‘Best to leave it,’ I say. ‘I’ll use an app, it’s easier.’

‘Right.’ There’s a lengthy pause. I wonder whether I can hang up, but the choice is taken away from me when he does so first. I throw the phone on to the bed and take a long, hot shower, shaving carefully, then use the hairdryer to plump up my blond curls. I know how innocent they make me look, and I might as well take advantage of that. My face has a childlike aspect to it, making me appear younger than my twenty-two years. More innocent. If I wasn’t so well known in the city, I’d have trouble getting served in bars. As it is, the only difficulty I have is paying for my own drinks. When I go out, girls want to get close to me and boys want to be my best friend. When I went out, I mean. I don’t any more, for obvious reasons. The only person I see regularly is Wojciech, and even he seems to be reconsidering our relationship. We go to a local pub sometimes, one where the regulars have no interest in football, and I keep my back to the room and pull a baseball cap down over my forehead. More often than not, though, he just comes here, and we watch a movie together, my head in his lap. I like how he strokes my hair. Mam used to do that when I was a boy, lying on the sofa watching Toy Story over and over. Cormac and I knew every line of that film and, when we were children, we would go to each other’s houses and act out scenes for our parents, who howled with laughter, even Dad, who only allows himself a handful of smiles a year, as if each one costs him something he can’t afford. We were so close, Cormac and I, united as much by having known each other since we were babies as by the fact that I had no siblings, while his only brother, his senior by only a year, had been killed in an accident when we were seven. He’d never quite got over Ronan’s death, traumatized at an age when he would either move past it quickly or not recover at all, and he clung to me in his grief.

I open one of my many wardrobes and stare at the suits within, most of which I don’t recognize, since I don’t buy my own clothes. The club employs a woman, Lucy, who takes care of all that for us. She stores all the players’ measurements – shirt size, shoe size, trouser length – on her laptop and seems to understand instinctively what will look best on each of us. Every month two boxes arrive, one from Nike, because they’re my sponsor – were my sponsor – and the other from one of the big luxury brands. If I’m photographed in them, and those pictures subsequently appear in the papers, my account is credited with 30–50 per cent of their value, depending on the publication. I don’t wash my boxers or socks; they go straight in the bin after a single use. There’s always dozens more waiting in my underwear drawer. I’ve been given clear instructions on how to dress today: relatable but aspirational. It’s important that I look like I care enough about, or at least respect, what’s happening to make an effort, but that I’m too distressed by the injustice of it all to try too hard. In the end, I select a dark blue Armani suit with a white Balenciaga shirt and a navy Tom Ford tie. A pair of dark brown Ted Baker shoes that feel uncomfortable on my precious feet. Maybe if I wear them long enough, I can cause some permanent damage and be set free.

“If it ends badly, they’ll never speak of us again.

We’ll be erased from their records as if we never existed.”

Before I dress, however, I examine my body in the bedroom’s full-length mirror. My left arm is a little stiff this morning, which it occasionally is when I feel stressed. I broke it a few years ago – or rather, I had it broken for me – and it’s never been quite the same since. But I’m still toned, since I use the building’s gym and private pool most days, although the definition of my abdominals has diminished a little. Neither Robbie nor I are allowed anywhere near the club right now, so I can’t eat in the players’ canteen, where the food is carefully prepared and nutritionally balanced, so my diet has slipped. A private trainer shows up three times a week, supplied by the club, and this is something we’re not allowed to tell anyone. Robbie’s worth more than ten million pounds, and I’m valued at just over half that amount, so it needs to protect its assets. When this is over, if it goes our way, we’ll be expected back on the pitch as soon as possible. If it ends badly, they’ll never speak of us again. We’ll be erased from their records as if we never existed and, I imagine, the insurance will kick in.

By nine fifteen, I’m dressed, and I return to the window, waiting for Robbie to leave. I’m only there a few minutes when a taxi pulls up and he emerges from the front entrance. Only when it drives away do I open the app and order one for myself. I could have travelled with him, of course, but Catherine, our barrister, said it would look better if we arrived separately.

When the driver pulls up, I’m standing by the small area of overgrown grass which houses the development’s performative commitment to the environment, a wild sanctuary that allows insects and birds to land or nest without disturbance. It has a rough beauty to it, but it contains a secret in its depths, and I become so lost in thought that the driver has to sound his horn to snap me out of it. I turn away, open the back door and step inside. I’ve entered my destination already, so there should be no need for conversation. I keep my head low, pretending to scroll through my phone, and it’s only when we’re halfway there that I notice how he keeps glancing at me in the rear-view mirror.

‘I know who you are,’ he says.

I don’t reply.

‘It starts today, doesn’t it?’

I nod.

‘I’m a fan,’ he tells me, his face breaking into a wide smile. ‘That goal you scored against—’

‘Thanks,’ I say. I have no interest in reliving the highlights of my brief career.

‘So how long will it go on?’ he asks.

‘A couple of weeks, I’m told.’

‘If you like,’ he says, ‘I could pick you up every morning. And then, when you’re done for the day, I could be waiting outside. Might make life easier for you.’

He’s not wrong. It would be more convenient to use the same taxi and driver throughout this whole ordeal. After a day or two, he’ll grow tired of interrogating me.

‘All right,’ I say.

‘What time should I come back for you today?’

‘Four.’

‘And pick-up tomorrow at nine thirty?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ll bill you when it’s all over.’

‘Fine.’

‘So don’t go to jail.’

My teeth grind against each other.

‘And do I call you Evan or Mr Keogh?’

‘Evan’s fine,’ I tell him.

‘Then I’m Max,’ he says, reaching into a pocket between the two front seats and extracting a pack of business cards before passing one back. ‘All my details are on there. But you don’t need to worry. I’ll be where I’m supposed to be.’

‘Thanks,’ I say.

As he turns a corner, the courthouse appears in sight, and I see the media scrum outside. I realize now that I should have left before Robbie. Then I could have been inside when he pulled up and they would have turned their attention towards him. He’s the bigger star, after all. Now they’ll focus on me.

We pull up and I reach for the door handle.

‘Give ’em hell, lad,’ says Max, turning around and grinning. His teeth are yellow and his lips badly chapped.

Hair springs from beneath the collar of his shirt, his eyebrows, his ears, his nose. He’s an unkempt forest of a man. ‘Remember, any girl who takes on two lads like that is nothing more than a cheap little whore, and the jury will see that. You think I’ve never been there? Some girl saying no when you know they mean yes? More times than I can count.’

I imagine how it would feel to pull his head towards me and smash it into the gap between the seats, to keep pounding it against the cheap interior until I’ve ended him. But I do nothing. Instead, I simply nod, open the door and step outside, the flash of the cameras and the shouting of the reporters overwhelming me, like I’m arriving for a film premiere and not a rape trial. I wonder, as Max drives away, does he notice me crush his business card within my fist and toss it away, flicking it with my index finger so it lands in the dark soil of the bushes outside the building. He can come back at four if he wants, but I won’t be waiting for him.

A policeman approaches. I think he’s going to guide me into the courthouse, but no, he reprimands me for littering, making me pick up the card while the photographers snap away and the journalists roar my name. It’s dirty now, covered with moist earth, and muddies the fingers of my left hand, but I don’t want to wipe them against my suit, so I wait until I enter the building, where the people standing in the lobby turn to look at me, then discard it in the nearest bin and run my hand under a sanitizing tap, a holdover from the days of the pandemic, when we could all stay inside, alone, and avoid the world entirely.

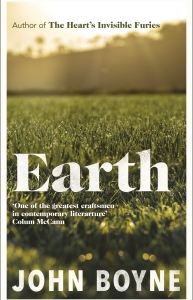

Extracted from Earth by John Boyne, out now.

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

Extract: Argylle by Elly Conway