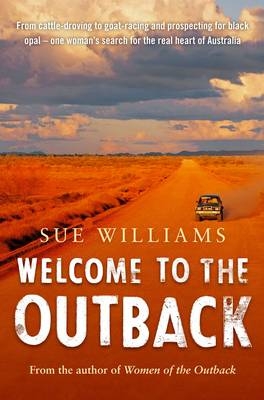

Information about the book

I can't breathe. I'm choking. The more I try to swallow, the more I can feel my throat close up. I gasp and try to gulp in air. But it doesn't work. I just cough and rasp for breath. I'm suffocating . . .

'Get some water!' I can hear someone shout at me. 'Over there! Over there! In the trough!' I spin around to see a trough full of muddy brown water. I dash over and greedily scoop up handfuls, slurping down the water as if my life depends on it. Because it well might. At last, I can breathe again, but I race back to the table, where another square of dry damper is waiting for me. I have to get that down to move onto the next challenge.

When I was first invited to take part in the 'Battle of the Greenhide' Drovers' Cook Ironwoman Competition, I wasn't sure what it would entail. 'But you should do it!' urged Sonya Cullen, events manager at Longreach's Australian Stockman's Hall of Fame. 'It's hard, but it'll be fun.' Fun? This? I've had more fun in a waxing salon.

We begin by lying in a swag, then, when the starting bell sounds, scramble out, roll it up (and I'm surprised to discover how heavy and cumbersome it is) and run to the trough of dirty water. There, we splash the freezing water onto our faces, then race to the table of damper. Coughing and spluttering, we have to chew and swallow it – opening our mouths for the judges' inspection to make sure it has really gone down – before we can move onto the next stage. But it seems if you're prepared to risk your life by swallowing some of the filthy water just to get the damper down, then the rules are the least of your problems.

When finally I manage to swallow enough damper, I have to run off to pick up a hessian bag full of straw, which doubles as a sheep, sling it over my shoulder and then traverse a muddy dam to get it safely to the other side. I fall flat on my face in the mud almost as soon as I step into the dam. It's a struggle to get up again, with my wet 'sheep' now feeling more like it's stuffed with bricks. Then I go back to get another one . . .

But I try to smile as I flounder my way through the race. After all, this is nothing compared to the discomforts the real drovers used to face every day in the Outback. I know that now. I'm here at the 21st anniversary drovers' reunion weekend to learn all about droving from the men who did it over a lifetime, pushing stock throughout the country, swimming them across treacherous, crocodile-infested rivers, and over some of the most desolate land to help make the Outback, and Australia, what it is today.

While I've heard so much about the Outback, its luminous landscapes, the tough characters it breeds and the romance of its wide open spaces – so much a part of our national psyche – I've never really spent much time there. I've met some of its extraordinary people and written about how much they love living in some of the most remote areas of the country. I've been told firsthand how they'd often had to overcome enormous challenges to survive in such incredible isolation, but I could never quite work out what they liked about the Outback and why they stayed. I always wondered what stopped them from just upping sticks at the first sign of trouble and moving to the nearest city – where, let's be honest here, there were far easier jobs available, plenty of transport, good roads, neighbours next door rather than a three-hour drive away, neat quarter-acre blocks (or even pleasant apartment buildings), the choice of thousands of people to socialise with, fresh food, 24-hour medical centres, nice cafés, hairdressers you didn't have to book weeks in advance for a quick trim, cinemas, ice-cream . . . Yet few ever did; they'd shudder at the very thought. Instead, they invariably chose to stay in the Outback, which always looked to me to have pretty much nothing there but dust and dirt and sand and flies and unbearable heat and hardship.

But after having heard from so many people how wondrous the land out back is, I felt it was finally time to see for myself. I had a few months spare from pressing work deadlines so why not spend that time scouring the Outback, battling the elements in search of the real heart of Australia? What is the Outback? Where is it? Is it really worth preserving? And am I really up to the challenge of finding out?

That, perhaps, was my greatest worry. After all, English-born, I've spent my whole life in cities. Even as an enthusiastic new Australian who's been here for over 20 years, I still rarely roam beyond cities' outer suburbs. The ridicule I faced a couple of years ago out in the bush after I excitedly called a newborn lamb a 'sheepling' still burns. So even now as a cityslicker living in a high-rise apartment in Sydney's Kings Cross – the most densely populated area of the country's biggest city – I know I am perhaps not the ideal person to solve the mystery of the Outback's appeal. Wide open spaces scare me. Far horizons just don't look right without skyscrapers. I thrive on noise, crowds, traffic, stress, 24-hour cafés and a supermarket three minutes away that stays open till midnight.

What's more, I'm a vegetarian teetotaller with a slight gluten intolerance and an over-sensitivity to caffeine. I know it's tough getting by in places where the traditional diet is often steak, damper, billy tea and oceans of beer. Turning up at cattle stations and asking for cheese in lieu of meat isn't the best way to guarantee a warm welcome, surprisingly. Refusing alcohol is perhaps even worse. And I'll never forget when I first turned down an offer of tea and produced my own herbal teabag instead. 'What?' the elderly lady barked at me. 'Our tea not good enough for you?'

Then there was the time I tried to drive down the Gibb River Road through the Kimberley. The heavy rain of the approaching wet season had turned the track into a swamp and all I could do was sit on the ground and watch the thunderstorms light up the sky for hundreds of kilometres around – and wonder how on earth I'd get out again. Or the pitch-black night I went for a stroll in the desert near South Australia's Oodnadatta, and couldn't find my way back again. Or that afternoon I went out with an elderly Aboriginal tracker to search for bush food and watched him nimbly leap over a chasm, and felt too embarrassed to tell him that there was no way I could do the same. Sadly, I was right. Although my guide tried gamely to catch me, he couldn't, and my dislocated shoulder took six months of physio to heal. After each trip to the Outback, I'd returned to the city with a huge sigh of relief.

Even so, this trip, I vowed, would be different. I'd work hard to find the true heart of Outback Australia, in all its glory, desolation, laughter, lunacy, romance, passion and spirit of adventure.

So I pulled out the maps and started researching interesting Outback-y things to do and good people to see. One of the first things that jumped out at me was a cattle drive in Aramac, in Outback Queensland. And the second was this drovers' reunion in Longreach, where old-timers would gather and share their stories of life in the saddle. I thought the coincidence was an excellent omen for the start of my Outback travels. The drovers would doubtless be able to offer a wealth of great tips for surviving the cattle drive and I'd be a superb listener – as only a person who can't ride and, to be honest, is just a teensy bit scared of cows, could hope to be.