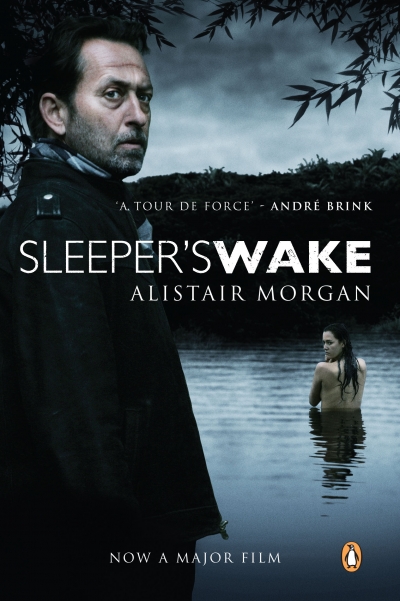

Information about the book

If there is no dignity in death, then there is even less dignity in deciding who should be apportioned the most amount of mourning: my wife or my child. I cannot decide, or rather, I do not want to decide. Often there is more sorrow expressed for a child’s lost life because of all the unrealised potential. For an adult there may still be some potential, but there is also a trail of failures, of half completed goals and the uncomfortable recognition of personal limits. But to die in your prime before reaping anything of your labours is somehow, to me, crueller than dying long before your adult life has even started. Right now that is my feeling on it. No doubt my mind will change.

When I close my eyes I can see Deborah’s face in front of mine. Her expression is calm. I can see all her features clearly, particularly her dark eyes, with slight bags starting to form beneath them from the many late nights she spent working at her laptop. Even on holiday she would sometimes spend several hours a day working on insurance policies for her corporate clients or phoning various brokers. But I could hardly complain: it was always her salary that paid for our holidays, including our final holiday in Mozambique.

Even though I try to resist, my mind salvages other images of Deborah’s body: her breasts, still well shaped and heavy even after having suckled a child; her legs, muscled and slightly pocked at the tops of the thighs with cellulite (how many times had I sworn to her that I couldn’t see it?); her hair: short, black, business-like. And then, between her legs, that soft hairy slope that I’d learnt to locate and identify under all descriptions of bedclothes and underwear. I literally have to slap myself to stop these flashes, these violent burglaries of my memory banks.

Although Deborah was compact in build her body gave off more heat than mine. In bed she would want the duvet off when I still wanted to be covered by it. Eventually we decided to sleep under separate duvets, happy to be independent of one another’s bodies. (This was just one of the many compromises that crept into our marital bed over the years.) But now Deborah’s physical absence is like a ghost pain to my body. I am frequently stirred from shallow pools of sleep, convinced that I felt her leg or arm brushing against me. And even though I have taken to sleeping on the sofa in the lounge since my return from hospital, I still put my arm out towards my left to search the emptiness that now lies beside me.

Sometimes I get up in the middle of the night and creep around the house to see if, by some loophole in the laws of death, any of the flowers have returned to life. Maybe it’s just a recurrent dream, fuelled by the last embers of my hope. When I was a boy I used to catch flies and imprison them in the freezer. After an hour I’d take their frozen bodies out into the sun, and then watch in fascination as they gradually thawed and flew away. Or was that a myth someone told me a long time ago?

I have spoken to Kaashiefa about my nocturnal checks on the flowers. Not that I feel the need to have my behaviour analysed by her – I know myself well enough – but I thought I’d throw her a crumb anyway. Something for her to chew on after all the silence I’ve offered up in the past week. Although I don’t know why I encourage her. Like a stray cat she’ll only keep on turning up at my doorstep for more titbits. I allow her into my home because I’ve been told to by people who supposedly know what’s good for me, just as I have been told to take certain pills. But I don’t need her here. And I don’t need the pills anymore either. I want to feel whatever it is I have to feel.

It is an insult to Deborah and Isabelle not to allow myself to feel, with every particle in my body, the pain of their deaths. It hasn’t arrived yet. But it is coming. I can see it nearing the coastline, like a tropical cyclone on a television weather report. Common sense says that I should get out of town, that I should hammer planks of wood over the windows and flee with whatever possessions I can carry in my arms. But what’s the point? I cannot hide from this storm. The only shelter I can take will be that provided by the drugs. But their use has passed. Last night I flushed the lot down the toilet. Already I can feel my senses gradually beginning to thaw.