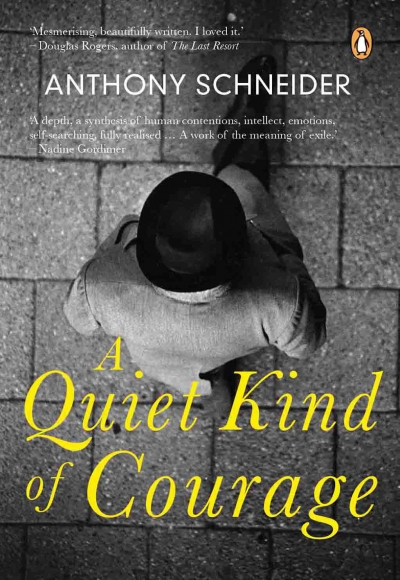

Information about the book

An afternoon meeting with Colin Beswick. Afterwards Henry walked with Nellie in the garden. At the back of the property, half hidden by trees, near the neighbour’s wall, stood an empty fountain shrouded in vines. A blue semi-circular pool ringed with shiny silver-green tiles, like fish scales. Henry and Nellie sat on the low fountain wall, facing the garden, their backs to the overgrown wall and dry spout. At the far side of the garden, pink pincushions dotted the green shrubs.

‘We never grew flowers when I was a girl, only vegetables,’ Nellie said.

‘Where was that?’

‘Breyton. Do you know it?’

‘No.’

‘You wouldn’t. I was three before I saw a white man.’ She looked around. ‘Where are we now? We’re in no man’s land.’

‘A very pretty no man’s land,’ Henry replied.

Some days later, Henry took two Lion Lagers to the cottage. Nellie opened the door, wearing a black skirt and a white cotton shirt.

‘Sanibonani, Henry.’

‘Sanibonani.’ He held out the beers. ‘Can I buy the lady a drink?’

‘I think you already did.’

Long slender face, dark eyes, skin the colour of dark chocolate, her short Afro soft and sheeny. Henry had never seen a black woman this beautiful up close before. In meetings, at Ezekiel’s side, she’d always been a comrade, someone else’s wife, and maybe, yes, he wasn’t accustomed to looking at black women that way. What way? Beautiful, desirable.

They walked in the garden, then sat on the fountain wall and drank their beers. She told him she spent most of her days reading. Dickens, Harold Robbins, Fugard’s new play, Blood Knot. Colin had a good library and she availed herself of it.

They sat in the dappled shade looking across the lawn at the jacarandas, shrubs and pincushions, the lilac sky. An old wheelbarrow stood beside the garage wall.

‘So peaceful here,’ she said. ‘It’s hard not to want everything to stay like this. Don’t you think?’

‘Do you mean that rich whites don’t want things to change?’

‘I meant here, this house. But I can understand their fears, their feelings, can’t you?’

‘I think equal rights are more important than pretty gardens.’

She laughed, low and warm, covering her mouth with her hand.

‘The land shall be shared among those who work it,’ he said.

‘These freedoms we will fight for. Side by side.’

Side by side. A promise, a prayer.

She leaned back, tilted her face to the sky. Henry could see the silky brown skin of her neck and her clavicles and shoulders.

‘Where are you from, Henry?’

He told her what he remembered about Lithuania and Liverpool, and she described her village near the Swaziland border. Her brothers had been herd boys. Her father had worked for the Roads Department. Henry could smell the minty scent of her hair as they talked about their children. Nellie’s daughter, Thandi, was two years older than Glenn, and Simon was in high school. They’d grown up in Breyton with Nellie’s parents. After Nellie moved to Johannesburg, she saw them once every two or three months at most. She took them presents – books or clothes for Simon, a doll for Thandi – and they all helped her father with his small parcel of land, planting seeds or harvesting the mealies. But they were older now, living in Alexandra township with Zeke’s sister so that they could attend a proper school. Recently, she’d been able to see them more often. That is, until Zeke went into exile and she ‘disappeared’.

They showed each other photos, Glenn bare-kneed in his school uniform, sitting on a stone wall at St John’s, Simon in his black glasses, little Thandi in a white dress a size too big. Henry said maybe the children would meet soon. Nellie smiled and said yes, maybe.

‘How much have you seen them, since moving here?’

‘Once.’

‘That’s not a lot.’

‘No, it’s not. But I’m used to not seeing them very often. It’s how blacks must live in this country. We are robbed of our families – not just our land, liberty and human rights.’

‘You’d better amend the Freedom Charter.’

She laughed.

They watched the sun sink into the trees. The last of the jacaranda blooms were drooping, dark as grapes, and every time the wind blew a few more tumbled earthward.

‘You can’t risk seeing your children because you might get caught,’ Henry said.

‘It would be dangerous for them, but also for the cause. We can’t think only of ourselves.’

‘So you wouldn’t be seen with me.’

‘If I was seen with you, everyone who saw us would be suspicious.’

‘I know. But it might be nice to go somewhere else with you, other than this house, this garden.’

‘What’s wrong with this garden?’

He didn’t answer.

‘We can’t,’ she said. ‘You know we can’t.’

He told her about his years at university, the law firm, trips he’d taken, places he wanted to go. She told him about her decision to leave Breyton, taking the bus to Johannesburg with all that was important to her in a second-hand suitcase. He watched as she spoke – the movement of her mouth, the tiny striations in her lips – mesmerised by the sound of her voice. The thrill of looking at her fingers or the splash of freckles on her cheeks. Watching her, he felt a brightness bursting inside him.

He touched her hand then. Just three fingers on top of hers. Felt a tingle as her fingers stroked his.

‘Beautiful hands,’ he said.

‘Izandla ezinhle.’

‘Izandla ezinhle,’ he repeated.

‘Ngiyabonga.’