Sometime in early May 1982, Mike Fuller called me. “Listen, we’ve been invited to perform in Soweto at the Jabulani Amphitheatre,” he said.

Taken aback, I asked, “How come?”

“Well, ‘You’re So Good to Me’ is a big hit on the Radio Zulu charts,” he offered.

“Radio Zulu?” I shot back, astonished.

“So, do you want to do it?”

“Ja, cool, I’ll do it,” I agreed.

I grew increasingly excited about the gig and spoke to the guys in the band. We had only been performing in clubs to white audiences and this would offer something different. By then Bones had replaced Geoff Sedgwick on keyboards and he, too, was keen, as was Alistair. George van Dyk, our bass player, was from a working-class Afrikaans background and much more cautious about playing in Soweto.

George, who came from a conservative family, had been subjected to much more pressure about the fact that he played in a rock band and had been viewed as an “outcast” when he first joined Hotline. Rock music was viewed as a potentially “bad influence” by closed-minded white South Africans threatened by anything that filtered into South Africa from abroad.

Also the grand narrative in the media, particularly the state-controlled public broadcaster, the SABC, was that Soweto (or any township for that matter) was a dangerous place, especially for white people. The irony is that the inhabitants of townships were more likely to experience institutionalised violence from the state than anyone else, so the reality was that townships were dangerous places for black people.

On 12 May a second bomb had exploded at the West Rand Administration Board in Meadowlands, Soweto. The first had gone off in the same offices in January that year. There had been other attacks around the country, including Koeberg Power Station and the Langa Commissioner’s Court in Cape Town.

It was forgivable then, perhaps, that George was apprehensive about playing in a township.

“Are you mad? We can’t do that,” was his first response when I told him about the invite.

“Ah, come on, George. It’s in a big stadium. The other guys are going. We’ve been invited, man. Let’s go,” I cajoled.

I had not been programmed to think anything about playing in Soweto. I knew that the government was wrong but at the age of 20 it was on more of a visceral and emotional level than intellectual. I hated injustice, always had, but I had never encountered it face to face. The concert, which had been arranged by Radio Zulu, was due to take place on 31 May, Republic Day. It was a Monday and a public holiday, a day off that would have been taken very seriously by those white South Africans who celebrated the country’s “independence” from the Commonwealth.

It was also a potentially strategic day for any possible “action” by MK cadres as it would send a clear message to government, and so generally police would have been on high alert. I was still living with Paulette in Johannesburg and on the set day Paulette, Alistair, Bones and I piled into our white Ford Escort with the one black door, followed by George and Larry Rose (who was our drummer at the time) in a Grey Datsun and we headed north to Soweto.

We had been given written directions and sort-of vaguely knew where it was. We took the Old Potch Road and turned off near Sun Valley and the famous Vic’s Viking Garage at Devland with the Vickers Viking aircraft on its roof. In 1982 Soweto was nothing like the vibrant, built-up city with malls, shops, cinemas and double-lane highway it is today. Back then the turnoff to Soweto was a dust road and the township seemed to be shrouded in a permanent blanket of fog from coal fires people were forced to use for cooking and heating.

The streets were unpaved and it appeared as if the primary mode of transport was the donkey cart. Mangy, thin dogs roamed the streets and children pushed homemade wire toys through the dust and puddles. The two most permanent-looking buildings were Baragwanath Hospital and Black Chain Supermarket.

Unsurprisingly, we encountered a road block shortly after we had turned off. An armed white policeman swaggered towards our car. There was no way they were going to let two cars transporting six white people into a township without finding out why we were there.

Back then white journalists were prohibited from entering townships without prior permission and a permit issued by the police, which was one method of censoring the media or at least restricting movement. Police often suggested to white people that we were not allowed to enter a “black area” without official permission.

“Lady, do you know where you are?” the cop asked as he leaned in towards the window and scanned the interior of the car.

“Of course I know where I am, there is a huge brown board behind you with the white lettering ‘Soweto’ on it,” I replied facetiously.

“Well, you can’t come in here,” he charged.

“What do you mean ‘can’t come in here’? We are coming in here! We’ve been invited to play at a concert at Jabulani Amphitheatre.”

The cop’s eyes bored into me, as well as the wide-eyed occupants of the car behind us. The cop said something in Afrikaans, which I informed him I didn’t understand. George got out of the Datsun behind us and approached. I wondered if the cop thought that finally a man was coming to talk some sense into this loud-mouthed, bolshie woman who seemed inexplicably, to him, to be in charge.

“Do you think it’s a good idea?” George hesitantly asked.

“Of course it is. We are going to perform today,” I told him before he turned and walked back to their car. He knew better than to argue with me.

The cop shook his head and said, “Well, then be it on your own head, girly. You are on your own,” before waving us through.

We snaked our way through White City, which back then consisted of rows and rows of prefabricated houses with domed roofs that looked like the tops of mushrooms. And then suddenly, Jabulani Amphitheatre loomed like a moving, writhing bulwark up ahead of us. I had never seen anything like it. It was about one o’clock and scorching hot. From the outside approach I could see the back of the stands behind the stage. There appeared to be a wall of people packed tight. A solid mass of humanity. Some people appeared to be hanging off the fencing that had been used to extend the seating capacity.

There was more to come. Security guards carrying long sjamboks pulled open a large, creaking iron gate and let us into the backstage parking area, which was already choc-ablock with cars parked haphazardly. There was a tremendous buzz inside the stadium. We got out of the car and as we walked to the dressing room behind the stage I caught another glimpse of what awaited us. From that angle I could see about half of the inside of the stadium and more people packed tightly together.

We only had a few moments to get ready to go on. In the meantime, Mike met us at the change room. Kansas City was up on the small, low concrete platform that served as a stage, talking to and coaxing the roaring crowd. It sounded like he spoke and that they replied en masse. Then he appeared backstage, a slightly built man in a pair of shiny bellbottom trousers. I remember Mike shaking his hand before guiding him towards us. Kansas had this wonderful open face, split by a huge smile. Then someone else bounded over and introduced himself as Collins Mashego, a co-compere of the afternoon’s show.

“Kan, these are the people whose song you have been playing,” said Collins, also a veteran broadcaster. Kansas shot us a broad, welcoming grin. Then things happened fast. There was clapping and cheering and we ran onto the stage, five white people, some in waist-high stonewashed denims and with funny big hair. Inside the stadium I could finally see that about 40 000 people had squashed into a venue built for around 30 000. People were crushed up near the stage and there was not a vacant spot on the field of red earth. The stadium contained a powerful, tangible energy. We had opted to start with what we regarded as one of our sure-fire “crossover” covers, Diana Ross’ disco hit, “I’m Coming Out”.

I looked out across a sea of very perplexed faces as I pushed through the song and could almost hear the audience thinking, “What the hell is this?” but in Zulu, or Xhosa or Tswana or Sesotho of course. Afterwards Collins bounded onto the stage and said something in Zulu that none of us understood (he told me later what he had said). George’s fear behind me was palpable. Collins signalled for us to continue and it was Alistair who had the presence of mind and who leaned over to me and said, “Let’s do ‘You’re So Good to Me’.”

We had planned to do the song in the middle of the set but Alistair was right, no one knew who the hell we were. He had understood the only way the audience was going to “recognise” us was if we sang the song that brought us here in the first place. Bones began to play opening notes on the keyboard and, as I opened my mouth to sing the first line, the crowd erupted. It was as if the penny had dropped; finally the audience could marry the song to the band. I watched with a growing sense of astonishment as almost everyone sang along. They knew every word!

It was an electric and humbling moment, one I have never forgotten. We played a few more songs to rapturous applause and approval. We played “You’re So Good to Me” a second time and received an even bigger round of applause. At the end of it Collins was back on the stage gesticulating at the band. The crowd hushed as he announced, “Today, today, we are going to marry this ntombazana to Soweto” to roars from the crowd. “What should we call her?” he asked.

And then, in what felt like a split second, the crowd responded as if with one voice: “Thandeka”, “Thandeka” – the loved one.

It is impossible to capture accurately the significance or feeling of the moment verbally or in the written word but, put simply, I felt as if I had been reborn. Perhaps this is how people feel when they are baptised in the sea or a river. A sense of positive, surreal displacement, a subtle internal shifting of a worldview, no, a world and my place in it. There was a clarity that arrived with a sudden and blinding realisation that, for the first time in my short life, I felt a true sense of belonging. I was enveloped by an energy and collective love that flowed in waves from the stands around me and onto the stage. It was a profound and sacred moment.

Then, out of nowhere, an old, wizened man appeared from the crowd, carefully balancing a calabash up to the stage. At the same time my eye was snagged by a man right up front near the stage who was being squashed and crushed into the concrete lip of the platform. It appeared as if it was going to end badly but instead some in the crowd surged forward, picked him up and plonked him on the stage. He had only one leg, the other was a stump that he managed to wiggle, and was on crutches, but that didn’t stop him from dancing wildly. There was something dreamlike about the events unfolding around us.

Collins took the calabash from the old man and passed it to me. Foam bubbled out of the cracked mouth. I had no idea what was inside and I honestly don’t remember what it tasted like but I gulped back the liquid to an approving, deafening bellow from the audience. The men in the band were not offered the calabash. It was my wedding after all! Three years later George, who had been so afraid to play in Soweto, was to write the now iconic “Jabulani”, a simple song that is now inexorably woven into the texture of this country’s musical history.

That hot afternoon in May 1982 we all stumbled off stage stunned and somehow altered. Paulette was there to greet me and all she could say was, “Wow”. Dazed we hung around while a few other acts performed, including Sipho Hotstix Mabuse and Harari who performed a distinctive rock/Afro beat, as well as Abakhwenyana and the Soul Brothers, early adopters and perhaps originators of township jive and Mbaqanga, with its driving bass and hypnotic percussive Hammond organ.

I understood much later that, while we were on our own musical journey, local music and each new sound that emerged were deeply influenced by political currents and each generation’s response to these. There was always jazz, the music of choice for the country’s thinkers and intellectuals. Marabi had made way for Mbaqanga just as Mbaqanga would make way for Afrosoul, pop and disco. Then came Kwaito, Hip Hop Pantsula and House. Each sound morphed into another unique, South African frequency. But there were always a few constants in the ever-changing sonic milieu, something instantly recognisable as uniquely South African. This would all form part of my later journey of discovery.

As we prepared to leave Jabulani Amphitheatre, I asked Collins what he had said to the audience in Zulu earlier in the day. I learned that audiences at township music concerts were totally unforgiving and were not averse to lobbing bottles and stones onto the stage if they disapproved of an act. In fact the sound engineers at the back of the stadium had bunkered down under a makeshift roof in order to protect themselves from flying projectiles. Collins had understood that this crowd might have turned nasty if the energies were not directed positively.

He told me then that he had explained to the crowd that it was Republic Day and that we, as white people, had chosen to come to Soweto to celebrate rather than with our “own” people. That, I realised, had set the scene for what happened later. We were all silent as we drove back home to Berea in the dusk on that Republic Day, 1982. Somehow, as the immediacy of what had just happened gave way to a deeper understanding, I knew that my life would never be the same again.

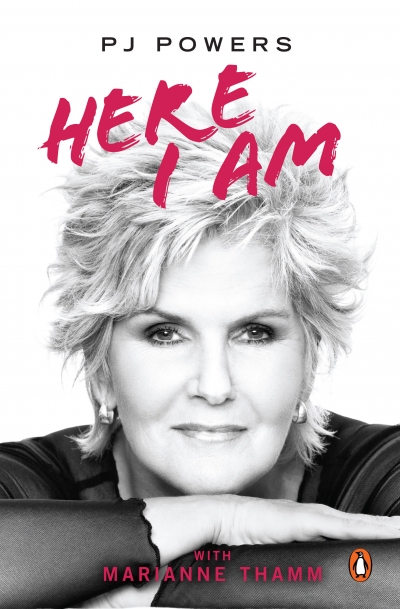

For more information on this title or to purchase a copy of PJ Powers: Here I Am online, click here.