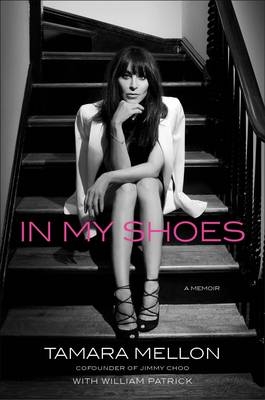

Information about the book

Chapter 1

I had just dragged myself to my desk at Vogue, yet again two hours late, when Anna Harvey, the deputy editor, appeared ominously at my shoulder.

“I need to speak to you,” she whispered.

Anna had been at Condé Nast forever and was very old school. Short dark hair. Wool suit and pearls. Cream Chanel blouse.

Eleven a.m. had become all too customary for my arrival, so I wasn’t entirely surprised to find a senior person wanting to have a chat. A day of reckoning had long been in the cards, and now I was just so very, very tired.

I got to my feet and walked with just the slightest hint of effort down the long corridor that led to her office. To my right, the open room where we editors sat. To my left, the glass boxes all in a row for the higher-ups. The decor was gleaming white, and everything around me had such a clean, bright look that it could have been a hospital. Or maybe it just seemed that way because I felt so ill. Nauseous and a little gauzy, as if I were jet-lagged. In fact, I’d been up all night at Tramp consuming prodigious quantities of cocaine and vodka. Then again, it could have been L’Equipée Anglaise. After enough drugs and drink the clubs do tend to blur.

I’d been at Vogue for five years at this point, and despite my afterhours indiscretions, I’d always worked very hard. I’d started off as the assistant to Sarajane Hoare, the fashion director, but when she decamped for Harper’s Bazaar in New York, I went to work for Jane Pickering. Eventually, I became accessories editor, a job that included putting together a page on belts and bags and shoes called “Last Look.”

The feature was called “Last Look” because it came last in the book, but lots of people told me it was the page that they looked for first. It wasn’t a fashion shoot with a model, but rather a collection with a theme. One month, it was Christmas gifts. Another, it would be “everything’s going metallic silver.” But now it appeared very likely that “Last Look” was going to be my last stand.

I followed Anna into her office and sat down across from her, confronting a woman with the exasperated mien of a schoolmistress pushed to the limit. I think what must have frustrated her most is that she could see that I had talent, but that talent alone was not going to save me.

“We think you’ve outgrown your job,” she began.

At Vogue they never said, “You’re fired.” They came up with encouraging euphemisms framed in the language of personal development.

I nodded and let out a great sigh of relief. It was all very polite. We exchanged a moment of warm and well-meaning eye contact, and then, leaving my things to pack up another day, I went home and slept all afternoon.

Introspection and self-awareness were not my strong suits in those days, and as I trundled home I did not fully appreciate the huge favour Anna was doing me. She was setting me up to mend my ways. She was also setting forces in motion that, in time, would lead to success far beyond anything I could ever have imagined. But if my subsequent history came as a surprise to me, it must have been absolutely mysti fying to those who knew me at this and at earlier stages of my development. Trust me. No one ever would have voted Tamara Yeardye “Most Likely to Succeed.”

---

Vogue House is in Hanover Square, near Oxford Circus, which is just across Hyde Park from Chester Square where, in 1995, I lived in the basement of my parents’ house. London real estate, especially in Belgravia, is ridiculously expensive, and the large houses usually have staff apartments that the older generation makes available to their less affluent adult children. My rather dodgy quarters had a separate en- trance with a door that connected to the main house, which I always tried to keep locked.

This modest attempt at privacy drove my mother nuts. Then again, my mother was unwell, which is a polite way of saying that she had severe emotional problems exacerbated by alcoholism, and though she was sober at this point, she was still not getting the help she needed. Certainly she has always been the most painful warp in the loom of my life. My very first memory is, in fact, of her pushing me across the bed and my hitting my head on a radiator. Had I spilled something? Made too much noise? All I remember is being so stunned that the pain took a moment to register, and then her loving words: “You’re not hurt. You didn’t even start crying until I came over.”

My mother’s alcoholic rants and cruelties were the bane of my childhood. But during the period of the Belgravia basement, her greatest perversity was in watching me follow the same path of chemical dependency and never saying a word.

For several years I’d been what you could call a functioning addict. When I wasn’t going out to clubs, I was falling asleep at eight p.m., but it wasn’t like ordinary sleep. What I did each night at home was a variation on passing out. Then the next morning I’d get up and drag myself in to work. If my child were living like that, I think I might have had something to say.

And it wasn’t as if my mother was completely indifferent to my existence. Whenever I was out she would go down to my room and search through my things, then make inappropriate comments to others about whatever she had found. I was with my boyfriend’s family once at their house in France and his father said to me, “Is it true that your mother has to go down and tidy up your underwear drawer?”

Cedric Middleton, the boyfriend, worked in finance, but that aside, he wasn’t the typically pale and priggish English public school boy. Cedric had gone to school in Switzerland, which is where the people who can afford it go when they can’t quite navigate a place like Eton or Harrow. He had an edge to him.

Cedric came from a lower aristocratic family and lived just around the corner—also in the basement of his parents’ home. It really was quite the fashion. A few years younger than I, he was handsome and tall with floppy brown hair, and he was really a lot of fun. We hung around with a crowd that was similarly favored by genealogy: Lucas White, Lord White’s son; Emily Oppenheimer, whose family once owned most of the diamonds in South Africa; Tara Palmer-Tomkinson, goddaughter to Prince Charles; and all-purpose “It girl” Tamara Beckwith, now a fixture in the British tabloids.

Our nocturnal habitat ranged from L’Equipée Anglaise in Marylebone to Tramp on Jermyn Street, a private club that had been around since “Swinging London” in the sixties. Johnny Gold, the owner, had played host to everyone from Sinatra and the Beatles to Lindsay Lohan and Dodi Fayed. He’d even known my father back in the day when Dad owned a similar venue and was still quite the man about town.

But by the time I’d reached the end of my career as a fashion editor, being “fabulous” on the dance floor but never quite sure of my exact whereabouts had become more trouble than it was worth. I had given my all to dissipation, and now, in a predictable twist to the unsavoury plot, I was unemployed. The only reason I’d been living unhappily under my parents’ roof was because, on a Vogue salary, I couldn’t afford to move out. Now I had no salary at all.

Lounging in my subterranean lair in the days just after my chat with Anna Harvey, I realized more and more that I had slipped into the realm of personal crisis. With Vogue out of the picture, what exactly was I going to do with my life? I had made good progress up from the depths of a less than stellar school career, and now I had pissed all that away.

More to the point, how was I going to get by? Was I going to live off my parents forever, piled on the sofa, wrapped in a duvet, eating guacamole and chips in a Belgravian version of Wayne’s World?

I needed a plan. So what did the self-help books advise us to do? Ask yourself, they say, “What do you love? What are you good at?”

Well, fashion, certainly. With perhaps a particular fixation on shoes that long predated “Last Look.” On Vogue shoots in Nepal I used to obsess over which pair of mukluks to wear. As a child of four, I’d finagled my way onto a school trip to Paris with the older girls, where I broke down in tears over a pair of red cowgirl boots, so much so that the nuns were forced to buy them for me.

For the past year or so I’d been germinating an entrepreneurial idea, and, necessity being the mother of many good things, now might just be the time to get on with it. There was a cobbler in the East End of London who had made a name for himself creating bespoke shoes for women of a certain pedigree. If Lady Windermere-Smythe or her daughter needed a shoe to match the exact hue of her dress, and assuming that she was content to wear either a pump or a slingback (those were the only two options), he was the go-to guy.

This cobbler, whose name was Jimmy Choo, worked out of a small shop in a Dickensian building on Kingsland Road that had once housed London’s Metropolitan Hospital. There was a tiny showroom with an old dirty carpet, a few wooden shelves with sample shoes on display, a sewing machine, and a worktable. It was hideous, but the Bentleys would pull up, the ladies would sit down and draw an outline of their feet on a piece of cardboard, and their shoes would be ready in time for the coming-out party, the wedding, or the viscount’s ball.

Jimmy had emerged as cobbler to the well-heeled in the 1980s, when the major fashion houses did not yet have the shoe lines they do today. Sergio Rossi was making high fashion footwear on the Continent, but the only fabulous, sexy shoes available in London were from Manolo Blahnik. Thus Jimmy became a service provider not only for society ladies in need of one-off shoes, but for editors as well.

Whenever we were planning a shoot at Vogue, one of us junior people would go down to his hideous little workshop in Hackney, past all the barbed wire and the metal grates, and we’d describe what we were doing. “It’s a gladiator story. . . . We need some flat gladiator sandals, only with silver metallic studs.” Just before the shoot—always at the last minute—his niece, Sandra, would show up to deliver the goods. We’d give him a fashion credit on the page, and then even more well-heeled ladies who read the fine print would find their way to his shop.

Jimmy was from Malaysia, where he had apprenticed to his cobbler father at the age of nine, cooking rice and running errands as well as learning to make shoes. As a teenager he’d come to London to attend the leather trade school, Cordwainers College, part of the London College of Fashion. The name “cordwainers” is derived from Cordoba, as in Spain, as in Cordoba leather. Ever since the London shoemaker’s guild was organized in 1271, they called themselves the Worshipful Company of Cordwainers. What I never realized until much later, and much to my regret, was that students at Cordwainers learned everything about how to make shoes, but not necessarily anything about how to design them. But that gets us ahead of our story.