When the call came, Maisie Beukes was alone in the keeper’s quarters. Cecil had already gone on duty even though it was only five o’clock. The call, she knew, would be from the Signal Office in the port. It should have been no different from any other routine call – to relay messages, to list supplies needed, to send news, to report on the light. The sole link with the outside world. Island to shore, lighthouse to lighthouse through the medium of the signalman’s radio phone. One lighthouse on its barren, bird-raddled plateau – the most forlorn in the world – the other at the edge of a city.

That afternoon, a black southeaster blowing, the static was intense. It was difficult to make out the words. Even after years of coaxing the radio-telephone and learning to interpret its sudden startling squeals and plummets – sea echoes, wind shear – Maisie could decipher little.

‘Hello? Can you hear me?’ shouted the signalman.

‘On and off!’ she yelled.

‘There’s been an accident in the lighthouse on the island. They need a doctor.’

‘What happened?’

The static crackled again. Maisie turned towards the window to look out at the bay as if, in doing so, she could make the distance smaller, gaze the voice into existence at the distant port. It was no day for a boat to be out. There were white horses right to the horizon.

‘Who needs the doctor?’

‘Mr Harker,’ shouted the signalman. ‘He fell down the tower.’

‘Oh my God! Is he alive?’

‘Yes. But something’s broken. I can’t be sure.’ His voice swooped and darted. ‘The guano headman called and reported it.’

‘You must send the tug and a doctor. I’ll get hold of a relief keeper to replace him.’

‘The weather’s terrible,’ the signalman said dubiously. ‘I don’t think the Port Captain will let anyone sail. And anyway, it’s nearly dark.’

Maisie did not contradict him. She said, ‘Phone again in an hour.’

‘Goed. Dankie, mevrou Beukes.’ And he was gone.

Maisie glanced out again at the far curve of the bay, the turbulent sea, the distant dune-fields. On impulse she called the Port Captain herself from the house telephone in her dining room.

‘Bad weather,’ he said.

‘It’s serious.’

‘Who is it?’

‘The Senior Lighthouse Inspector, Hannes Harker.’

‘It’s dangerous to try and land a man in the dark. The weather will calm down by tomorrow. Then we can make a decision.’

Maisie bristled. ‘He’s a lighthouse keeper, for God’s sake. If your tug was going down he’d walk on water to help you.’ She wiped her face with the back of her hand and drew a deep breath, calming herself. Only lighthouse people knew; their code was unimpeachable.

‘Has anyone got hold of the doctor?’ the Port Captain asked.

‘I phoned you first.’

‘Jis!’ he muttered under his breath. ‘This could be a balls-up.’

‘Sorry?’

‘OK, Mrs Beukes, listen. I’ll phone the doc and you find a relief keeper and I’ll come back to you.’

‘Be quick,’ said Maisie.

‘Stay put.’

Maisie went to the back door and called across the yard. The wind was strong enough to whip the white-bleached skin of broken shells from the pathway. ‘Cecil?’

No reply.

‘Cecil?’

A faint voice from the shed. ‘What is it, lovey?’

‘Come quickly.’ She peered out. ‘Cecil? I can’t leave in case the phone rings.’

Maisie went back into the kitchen and dragged the old kettle on to the hotplate of the coal stove. She pulled the tray across the counter, took the knitted cosy off the pot and emptied the cold tea leaves into the sink. There were two commandments known to all of them:

The light must not go out.

The keeper must not fall.

Hannes – so competent, so careful, so assured.

Something had distracted him. Or someone.

And who could possibly distract him on that island?

Maisie wiped her face again. A chill ran through her and she twitched her shoulders and leaned more firmly against the rail of the old coal stove. – Don’t be ridiculous, woman. She almost spoke aloud. She made the tea and set two cups. She carried the tray through to the lounge, a small waddle in her step, side to side, her slippers slapping quietly on the wooden floor.

The back door opened and her husband, Cecil, called from the porch. ‘What’s the matter, lovey? Are you hoping for a cup of tea?’

He came in, tugging down the edges of his old green jersey, his nose purple-veined from the wind outside, his knees pinched by the cold above his long grey socks. He looked at her. ‘Maisie? What’s the trouble?’

‘Hannes fell down the tower. He’s broken something. He must be in dreadful pain. That fellow from the signal room phoned. I got hold of the Port Captain and told him to send a tug.’

‘You should have asked me to do it.’ Cecil was admonishing. ‘What’s he going to think, being bossed by a woman?’

‘Don’t you talk nonsense, Cecil,’ retorted Maisie, the flush deep on her neck, her chin bobbing. ‘It’s Hannes, for God’s sake.’

‘Of course, lovey,’ Cecil said. ‘Sorry I spoke.’

‘We have to find a relief at once while they raise the doctor. They’ll call again soon so we must hurry.’

‘Ockie will have to take over there for a while,’ said Cecil. ‘He’s not going to like it.’

‘You’ll get exhausted here by yourself,’ objected Maisie. ‘Think about your heart, Cecil, and don’t be foolish. Can’t we phone Seal Point?’

‘Too far,’ he said laconically. ‘It’s Ockie or me. We can’t leave the light.’

Maisie said nothing. She knew the first rule just as well as he.

Cecil went away to the single quarters to speak to his assistant. Maisie did not follow him to hear Ockie grumble, sucking at his teeth and pulling at his great ear and glowering. She could hardly blame him. No one ever wanted such an exile. Even for a week.

Except Hannes. For him, a posting to the island was always going home.

When Cecil returned he said, ‘Ockie’s packing and then I’ll run him down to the harbour.’

He came and sat beside her on the settee, waiting: two old people, grey-headed, the steam from their cups drifting between them.

Then the telephone rang.

It was the Port Captain. ‘We’ll be leaving in an hour,’ he said.

‘My husband will bring the relief keeper down now,’ said Maisie.

‘The doc’s on his way.’

‘Good man,’ said Maisie as she put down the receiver.

‘Of course I’m a good man.’ Cecil reached for her hand. ‘Even your mother thought so.’

Maisie – comforted – half laughed. ‘You really are a good man,’ she said.

‘No matter all the other things my mother said!’ And she wiped her eyes.

Oh, Hannes. Not another blow. She rested the side of her head against Cecil’s shoulder. Then they turned simultaneously and in silence to peer through the salt-rimed glass at the darkening sea in the bay and the waves breaking as far as the horizon. The island lies five miles offshore – south-west from the densely wooded cape but thirty-one miles from port. Between it and the mainland is a channel, taupe green, cobalt blue. Sometimes that blue is all of the sky and sea, indivisible. And sometimes the heat bounces off the island rocks, an aura of fire, and the waves glitter as if scattered with mica chips. Sometimes the air is a tumult of gannets – a rising tide of wingbeats – and sometimes it is so still that the piping of a land-bird blown off course can be heard above the breathing of the sea. But when the southeaster blows, the wind whips the water to a saltgrey bile. Even its fish must flee the turbulence. Even the sharks. It is on those days that boats never venture near. Nothing comes except the wind – a great baleful beast.

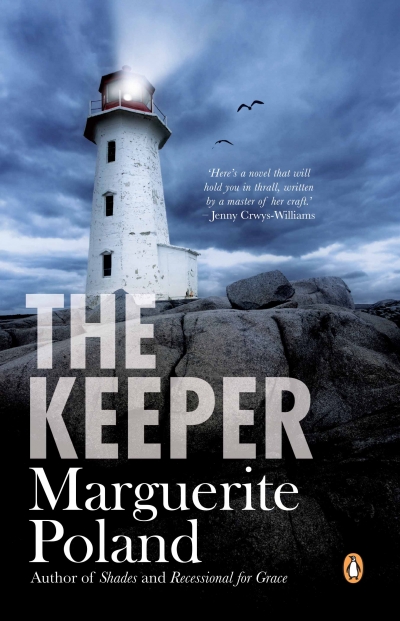

Click here for more information on this title or to purchase a copy online.