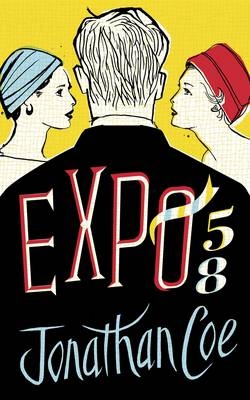

Information about the book

In a note dated 3 June 1954, the Belgian Ambassador in London conveyed an invitation to Her Majesty’s Government of Great Britain: an invitation to take part in a new World’s Fair which the Belgians were calling the ‘Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Bruxelles 1958’.

Five months later, on 24 November 1954, Her Majesty’s Government’s formal acceptance of the invitation was presented to the Ambassador, on the occasion of a visit to London by Baron Moens de Fernig, the Commissioner-General appointed by the Belgian government to undertake the work of organizing the exposition.

It would be the first such event since the end of the Second World War. It would be held at a time when the European nations involved in that war were moving ever closer towards peaceful cooperation and even union; and at a time, conversely, when political tensions between the NATO and Soviet bloc countries were at their height. It would be held at a time of unprecedented optimism about recent advances in the field of nuclear science; and at a time when that optimism was tempered by unprecedented anxiety about what might happen if these same advances were put to destructive, rather than benign, use. Symbolizing this great paradox, and standing at the very heart of the exhibition site, was to be an enormous metal structure known as the Atomium; conceived and designed by a British-born Belgian engineer called André Waterkeyn, it would stand more than one hundred metres tall and resemble, in its shape, the unit cell of an iron crystal magnified 165 billion times.

In the original letter of invitation, the purpose of the exhibition was described thus:

to facilitate a comparison of the multifarious activities of different peoples in the fields of thought, art, science, economic affairs and technology. Its method is to present an all-embracing view of the present achievements, spiritual or material, and the further aspirations of a rapidly changing world. Its final aim is to contribute to the development of a genuine unity of mankind, based upon respect for human personality.

History does not record how the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs reacted when he first read these impressive words. But Thomas’s guess was that, seeing four years of stress, argument and expense ahead of him, he let the invitation slip from his fingers, put his hands to his forehead and muttered: ‘Oh no . . . Those bloody Belgians . . .’ Thomas was a quiet man. That was his distinguishing feature. He worked at the Central Office of Information on Baker Street, and behind his back, his colleagues sometimes referred to him as ‘Gandhi’ because there were days when it was believed that he had taken a vow of silence. At the same time, and also behind his back, some of the secretaries had been heard to call him ‘Gary’ because he reminded them of Gary Cooper, while a rival faction knew him as ‘Dirk’, on account of a closer resemblance, in their eyes, to Dirk Bogarde. It could be agreed, at any rate, that Thomas was handsome, but he would have been astonished if anyone had ever told him this and, once in possession of the knowledge, he would have had no idea what to do with it. Gentleness and humility were the qualities which first struck people upon meeting him and it was only later (if at all) that they would begin to suspect a certain self-assurance, bordering on arrogance, lying beneath them. In the meantime, he was most often described as a ‘decent sort’ and ‘the unassuming, dependable type’.

He had worked at the COI for fourteen years, starting in 1944, when it was still called the Ministry of Information and he was only eighteen years old. He had started out as a post boy, and worked his way up surely – but very, very slowly – to his present rank as junior copywriter. Now he was thirty-two, and spent most of his working days drafting pamphlets on public health and safety, advising pedestrians of the best way to cross the road and cold-sufferers of the best way to avoid spreading germs in public places. Some days he looked back on his childhood and thought about his start in life (Thomas was the son of a pub landlord) and considered that he was doing very well; other days he found his work tedious and contemptible, and it felt as though he had been doing the same things for years, and he couldn’t wait to find some way of moving on.

Brussels had livened things up a bit, that was certain. The COI had been given overall responsibility for the content of the British pavilion at Expo 58 and this had immediately led to a frenzy of head-scratching and soul-searching around that maddening, elusive topic of ‘Britishness’. What did it mean to be British, in 1958? Nobody seemed to know. Britain was steeped in tradition, everybody agreed upon that: its traditions, its pageantry, its ceremony were admired and envied all over the world. At the same time, it was mired in the past: scared of innovation, riddled with archaic class distinctions, in thrall to a secretive and untouchable Establishment. Which way were you supposed to look, when defining Britishness? Forwards, or backwards?

It was a difficult conundrum; and the Foreign Secretary was not the only person to be found sitting at his desk, in the years leading up to Expo 58, muttering, ‘Those bloody Belgians . . .’ on long afternoons when the answers did not seem to come easily.

Some positive steps were taken. James Gardner, many of whose ideas had proved so inspiring at the Festival of Britain seven years earlier, was engaged as designer of the pavilion; and before long he came up with a geometric exterior which, by general consent, caught just the right combination of modernity and continuity. It had been allocated a very favourable position in the Exposition park on the Heysel plateau just north of Brussels. But what should go inside it? Millions of visitors were expected to flock to the Expo, from all over the world, including the African and Soviet bloc countries. The Americans and the Soviets were bound to produce national displays on a massive scale. What sort of self-image did the British want to project, given the opportunity of such a vast global stage, and such a curious and diverse audience?

Nobody appeared to know the answer. But by common consent, Gardner’s pavilion was going to be a thing of beauty: that was beyond dispute. And, if it was any consolation, there was one other thing that everybody was agreed about: the pub. Visitors to the Expo would need to be fed and watered, and if the national character was going to be expressed at all, this meant that somehow or other, next to the pavilion, they were going to have to build a British pub. And just in case anybody missed the point, the name of the pub would leave no room for ambiguity: it was going to be called the Britannia.

This afternoon, in the middle of February 1958, Thomas was checking the proofs of a pamphlet he had helped to put together for sale outside the pavilion: ‘Images of the United Kingdom’. There was a small body of text, interspersed with attractive woodcut illustrations by Barbara Jones. Thomas was checking the French version.

‘Le Grand-Bretagne vit de son commerce,’ he read. ‘Outre les marchandises, la Grande-Bretagne fait un commerce important de “services”: transports maritimes et aériens, tourisme, service bancaire, services d’assurance. La “City” de Londres, avec ses célèbres institutions comme la Banque d’Angleterre, la Bourse et la grand compagnie d’assurance “Lloyd’s”, est depuis longtemps la plus grand centre financier du monde.’

Thomas was just wondering whether the la in that last sentence was a mistake, and should be changed to the masculine, when his telephone rang, and Susan from the switchboard gave him the surprising news that Mr Cooke, Director of Exhibitions, wanted to see him in his office. At four o’clock that very afternoon.

The door was ajar, and Thomas could hear voices on the other side. Smooth, softly spoken, well-educated voices. The voices of Establishment men. He raised his hand to knock on the door, but fear made him hesitate. For the last ten years or more, he had been surrounded by voices like this at work: so why was he hesitating now, his hand almost shaking as it hovered over the wood panelling? Why was this situation any different?

It was strange how the fear never really seemed to go away.

‘Come in!’ one of the voices called, in response to his over-deferential tap.

Thomas took a deep breath, pushed the door open and stepped inside. It was the first time he had ever been admitted to Mr Cooke’s office. It was predictably grand: a hushed, calming environment of oak furniture and red leather, with two enormous sash windows reaching almost to the floor, offering a distant view of the windswept treetops of Regent’s Park. Mr Cooke was seated behind his desk, and his deputy, Mr Swaine, was seated to the right of him, next to the window. Standing before the fireplace, his grey-pink bald patch unforgivingly reflected in the gilt-framed mirror, was a man Thomas didn’t recognize. His dark worsted suit and stiff white collar gave little away: they were of a piece, however, with the navy-blue tie, discreetly embellished with what could confidently be identified as the crest of an Oxford or Cambridge college.

‘Ah, Foley.’ Mr Cooke rose to his feet and held out a welcoming hand. Thomas shook it weakly, more disconcerted than ever by this display of warmth. ‘Thank you for dropping by. Extremely decent of you. Lots on your plate today, I’m sure. You know Mr Swaine, of course? And this is Mr Ellis, of the Foreign Office.’

The unfamiliar man stepped forward and offered his hand. The grip was wary, lacking conviction.

‘Good to meet you, Foley. Cooke has been telling me a lot about you.’

Thomas didn’t see how this could possibly be true. He returned the handshake and nodded helplessly, lost for words. Finally he sat down, in response to a gesture of invitation from Mr Cooke.

‘Now then,’ said Mr Cooke, facing him from across the desk. ‘Mr Swaine tells me that you’ve been doing good work on the Brussels project. Excellent work.’

‘Thank you,’ Thomas mumbled, inclining his head towards Mr Swaine in a movement that was somewhere between a nod and a bow. Raising his voice slightly, in the knowledge that something more was expected of him, he added: ‘It’s been a challenge. An exciting challenge.’

‘Well, we’re all excited about Brussels,’ said Mr Swaine. ‘Tremendously excited. You can be sure of that.’

‘Brussels, in fact,’ said Mr Cooke, ‘is what we’ve brought you here to talk about. Swaine, you’d better fill him in.’

Mr Swaine now rose to his feet and, placing his hands behind his back, began to pace the room in the manner of a Latin teacher about to run through a list of verbal conjugations.

‘As you all know,’ he began, ‘the British exhibit at Brussels is divided into two sections. There is the official government pavilion, which is our baby here at the COI. We’ve all been busting a gut on this one for the last few months – not least young Foley here, who has been composing no end of captions and tour pamphlets and whatnot, and making a jolly fine job of it too, if I may say so. The government pavilion, of course, is essentially a cultural and historical display. We’re pretty close to the wire, now, and we still haven’t – ahem – still haven’t quite fine-tuned all the fiddly bits, but the . . . the essential shape of the thing is more or less settled. The idea is to sell – or should I say, to project – an image of the British character. Looking at things . . . looking at things, as I said, both historically and culturally – and also scientifically. We’re trying to look back, of course, on our rich and varied history. But we’re also trying to look forward. Looking forward to the . . . to the . . .’

He tailed off. The word seemed to be on the tip of his tongue.

‘To the future?’ Mr Ellis suggested.

Mr Swaine beamed at him. ‘Precisely. Back into the past, but also forward to the future. Both at the same time, if you catch my meaning.’ Mr Ellis and Mr Cooke nodded at him in unison. They both appeared to catch his meaning without difficulty. Whether Thomas caught it or not seemed to be of little consequence, at that moment. ‘And then,’ Mr Swaine continued, ‘there is the British Industries pavilion, which is a different kettle of fish altogether. That’s being knocked up by British Overseas Fairs, with the help of some of the high-up industrial bods, and the aim there is quite . . . quite particular, by comparison. We see the Industries Fair as being very much in the nature of a shop window. A large number of firms have been eager to take part, and they are all paying for the opportunity to be part of the display, so the idea is . . . well, the idea is to rustle up a good deal of business, we hope. It seems that this will be the only substantial privately sponsored pavilion in the whole fair, and naturally we’re very pleased that Britain is leading the way on this one.’

‘Of course. “A nation of shopkeepers,”’ said Mr Ellis. The quotation was delivered drily, but there was a certain thin satisfaction in his smile, all the same.

Mr Swaine seemed rather nonplussed by this intervention. For several seconds he stared absently into the fireplace which – even on this dismal February afternoon – remained cold and empty. In the end, Mr Cooke was obliged to prompt him:

‘All right, Swaine, so we have the official pavilion and we have the industrial pavilion. Isn’t there something else?’

‘Ah! Yes, of course.’ He snapped out of it and resumed his pacing. ‘There is something else, most definitely. Something which comes slap in the middle of the two, in fact. Naturally, I’m referring . . .’ He turned to Thomas. ‘Well, Foley, you don’t need me to tell you. You know exactly what comes between the two pavilions.’

Thomas did indeed. ‘The pub,’ he said. ‘The pub is what comes between.’

‘Exactly!’ said Mr Swaine. ‘The pub. The Britannia. A quaint old hostelry, as British as . . . bowler hats and fish and chips, representing the finest hospitality our nation can offer.’

Mr Ellis shuddered. ‘Those poor Belgians. That’s what we’re giving them, is it? Bangers and mash and last week’s pork pie, all washed down with a pint of lukewarm bitter. It’s enough to make you want to emigrate.’

‘In 1949,’ Mr Cooke reminded him, ‘a Yorkshire inn was constructed in Toronto, for the International Trade Fair. It was considered a great success. We hope to repeat that success; and indeed build on it.’

‘Well, to each his own,’ Mr Ellis conceded, with a shrug. ‘When I visit the fair, I shall be hunting down a bowl of moules and a decent bottle of Bordeaux. Meanwhile, my concern – our concern, I should say – is that this dubious venture should be properly organized, and overseen.’

Thomas wondered about the force of that plural pronoun. On whose behalf was Mr Ellis speaking? The Foreign Office, presumably . . .

‘Exactly, Ellis, exactly. We are of one mind.’ Mr Cooke conducted a vague search of his desk, found a cherrywood pipe and slipped it into his mouth, apparently with no thought of lighting it. ‘The trouble with this pub, you see, is its . . . provenance. Whitbread are going to set it up and run it. So in that sense it’s nothing to do with us. But the fact remains that it’s on our site. It will be seen, inevitably, as part of the official British presence. To my mind . . .’ (he puffed on the pipe as though it were burning merrily) ‘. . . this presents a definite problem.’

‘But not an insoluble problem, Cooke,’ said Mr Swaine, stepping forward from the fireplace. ‘By no means insoluble. All it means is that we have to be there, in some shape or form, to put our stamp on it – as it were – and make sure that . . . well, that things are as they should be.’

‘Quite,’ said Mr Ellis. ‘So, in effect, what is required is that someone from your office should be on hand – and indeed, on site – to run things. Or keep an eye on them, at the very least.’

It was very obtuse of him, but even at this stage Thomas could not see where he was supposed to fit into all this. He watched with increasing stupefaction as Mr Cooke opened the manila file beside him and began to flip languidly through its contents.

‘Now, Foley,’ he said, ‘I’ve been looking through your file here, and one or two things . . . One or two things seem to rather leap out at me. For instance, it says here –’ (he raised his eyes and glanced at Thomas questioningly, as though the information he had just lighted upon could hardly be credited) ‘– it says here that your mother was Belgian. Is that true?’

Thomas nodded. ‘She still is, if it comes to that. She was born in Leuven, but she had to leave at the beginning of the war – the Great War, that is – when she was ten years old.’

‘So you’re half-Belgian, in other words?’

‘Yes. But I’ve never been there.’

‘Leuven . . . Is that Flemish-speaking, or French?’

‘Flemish.’

‘I see. Speak any of the lingo?’

‘Not really. A few words.’

Mr Cooke returned to his file. ‘I’ve also been reading a little bit about your father’s . . . your father’s background.’ This time he actually shook his head while skimming over the pages, as if lost in rueful amazement. ‘It says here – it says here that your father actually runs a pub. Can that be true, as well?’

‘I’m afraid not, sir.’

‘Ah.’ Mr Cooke seemed torn between relief and disappointment.

‘He did run a pub, yes, for almost twenty years. He was the landlord of the Rose and Crown, in Leatherhead. But I’m afraid that my father died, three years ago. He was rather young. In his mid-fifties.’

Mr Cooke lowered his gaze. ‘I’m sorry to hear that, Foley.’

‘It was lung cancer. He was a heavy smoker.’

The three men stared at him, puzzled by this information.

‘A recent study has shown,’ Thomas explained carefully, ‘that there may be a link between smoking and lung cancer.’

‘Funny,’ Mr Swaine mused, aloud. ‘I always feel much healthier after a gasper or two.’

There was an embarrassed pause.

‘Well, Foley,’ said Mr Cooke, ‘this is pretty dreadful for you. You certainly have our commiserations.’

‘Thank you, sir. He’s been much missed, by my mother and me.’

‘Erm – yes, there is your father’s loss, of course,’ said Mr Cooke hastily, although it appeared that this was not what he’d actually been referring to. ‘But we were commiserating with you, rather, on your . . . start in life. What with one thing and another – the pub, and the Belgian thing – you must have felt pretty severely handicapped.’

Temporarily lost for words, Thomas could only let him speak on.

‘You made it into the local grammar, I see, so that must have been something. Still, you’ve done frightfully well, I think, to get where you have since then. Wouldn’t you agree, gentlemen? That young Foley here has shown a good deal of pluck, and determination?’

‘Rather,’ said Mr Swaine.

‘Absolutely,’ said Mr Ellis.

In the silence that followed, Thomas felt himself sinking into a state of absolute indifference to the conversation. He gazed through the sash window and out into the distance, towards the park, and while waiting for Mr Cooke to speak he had a savage craving to be there, walking alongside Sylvia, pushing the pram, both of them looking down at the baby as she lay deep in a dreamless, animal sleep.

‘Well, Foley,’ said the Central Office of Information’s Director of Exhibitions, slapping the file shut with sudden decisiveness, ‘it’s pretty obvious that you’re our man.’

‘Your man?’ said Thomas, his eyes slowly coming back into focus.

‘Our man, yes. Our man in Brussels.’

‘Brussels?’

‘Foley, have you not been listening? As Mr Ellis here was explaining, we need someone from the COI to oversee the whole running of the Britannia. We need someone on site, on the premises, for the whole six months of the fair. And that someone is going to be you.’

‘Me, sir? But . . .’

‘But what? Your father ran a pub for twenty years, didn’t he? So you must have learned something about it in that time.’

‘Yes, but . . .’

‘And your mother comes from Belgium, for Heaven’s sake. You’ve got Belgian blood coursing through your veins. It’ll be like a second home to you.’

‘But . . . But what about my family, sir? I can’t just abandon them for all that time. I’ve got a wife. We’ve got a little baby girl.’

Mr Cooke waved his hand airily. ‘Well, take them with you, if you like. Although a lot of men, quite frankly, would jump at the opportunity to get away from nappies and rattles for six months. I know I would have done, at your age.’ He beamed a happy smile around the room. ‘So, is it all settled, then?’

Thomas asked if he could have the weekend to think about it. Mr Cooke looked bemused and offended, but he agreed.