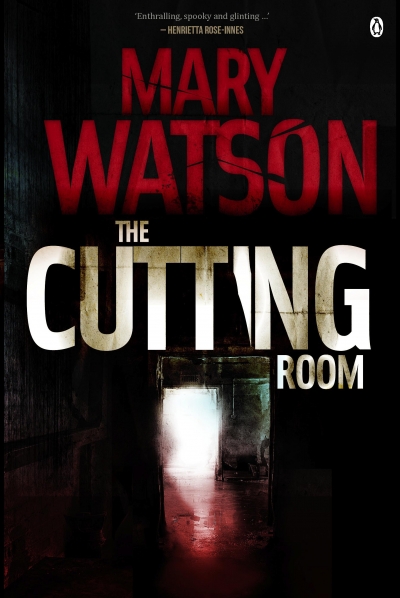

Information about the book

They came at dusk, three of them knocking at the front door. She first saw them through the glass panel in the wooden door. The mosaic of coloured glass was cracked, missing a thin finger of green glass. The wind had banged the door shut too many times and one flat hand pressing against the pane would cause the glass to fall inwards. The lead holding the glass together was weak and Lucinda had been meaning these last months to get it repaired. And now she stood, only fragile glass between her and three unknown men.

She opened the door – there seemed little else to do. But as she pulled the door towards her, Lucinda dug in her heels and willed herself large, big enough to fill the doorway.

‘Lucinda?’ the one with the moustache said it as a question, but his body language belied the uncertainty in his voice. He knew who she was, she could tell.

She was not surprised that she recognised one of them. He was more wiry than she remembered. That night in Cherry Red he’d been as bland as polony, she would not have remembered him if it hadn’t been for the bloodied nose. But it made sense that he should be here now. And with the other two flanking him he seemed dangerous. The moustache no longer a costume from a seventies film, it spoke of his stature. It said that he was a serious man, that she had better not mess.

‘We’ve come about Amir,’ the middle man added. ‘Mishka said you had some questions?’

He, Lucinda guessed, was probably the most dangerous of them all.

The oldest, Sean, had watery eyes turned downwards, like he was sad and tired. Resigned. One more thing on his to do list before he could get home to kiss his children goodnight: go and intimidate youngish woman. Lyle, the baby gangster, was still green and, Lucinda hoped, undecided about his future in the family business. It was the middle man, the one with the serious moustache, Clarence, who Lucinda was most wary of; he was the one to watch out for. He was the one who had climbed too slowly, the one who played second fiddle. If organised crime were like music.

‘He’s not here at the moment,’ she said, holding the door close to her.

Then they were inside. Lucinda wasn’t quite sure how that happened. Just the impression of a wave that couldn’t be held back. A sense of something beating down. They were ahead, walking through the passage towards the last of the daylight pouring through the large windows.

Lyle was out the glass door, on the deck looking at the view. He was young: his body was yet to ease into proportion – the head still too big, the arms and legs just about grown into his paws, but somehow wrongly fitted. He had a smattering of pimples across beautiful olive skin. She could tell the strength of his shoulders, of his arms. In a year or two he would be striking. Already there was a hint of sexual attractiveness which was quelled by the gawky limbs, by the smell of cheap hair gel, by the black moccasins.

Clarence was holding up the bottle of white wine and reading the label. He sniffed the bottle and turned to her, ‘Is it nice?’

The two older men were in their thirties, and already turned that corner from young men seeking thrills to middle-aged thugs. Their cheeks were puffed out, their middles layered by extra fat. They were not as tall as the young man, but Lucinda could see a familial resemblance. And she could see how the younger, too, within the next fifteen years, would thicken and then sag. Clarence continued to walk through the living room, looking around at her things. Touching this and that, picking up a letter, reading the salutation out loud (‘Doctor Parker and Miss Blankenberg’) then putting it down. Walking to the kitchen, he peered into the pan where prawns sizzled in white wine while the pasta leaned stiffly against the edge of the pot. The water had gone cold, Lucinda would have to boil it again.

He slurped the juice (‘needs more salt’), licked his tongue against the spoon and then put it back in the pan. She took the dirty spoon out and put it in the kitchen sink.

Sean was flicking through Screen. ‘Is it glamorous?’ he called from the dining room. ‘Working in the movies? Do you ever meet famous people?’

‘Depends what you mean by famous. But I’m an editor. I don’t go much on set.’ Lucinda stepped into the square arch between the kitchen and dining room. She could see Lyle fingering the CD collection in the living room beyond.

‘Lyle here wants to be an actor. Can you get him in? He loves Isidingo.’

Lucinda looked up at Lyle whose eye was lazily fixed on her while he slumped on the couch.

‘Might know some people. But he should get himself an agent. Now. If there’s nothing else, do you mind? I’ve got to get back to work this evening so I don’t have too much time.’

The men made their way to the front door.

‘One more thing,’ Clarence said as if he had forgotten. He stopped in front of Lucinda.

‘Mishka’s not really a good friend for you.’

Clarence stood close to her and then he brought himself a small bit closer. She could see the individual strands of his moustache and it was not so neat up close. She itched to say ‘you missed a spot’ but suspected that would earn her a harde clap. She felt his shirt just brush the top of her dress as he leaned across her. She remained still: she was very afraid. He kept his eyes on her as he picked up a wedding picture on the hall table.

‘What a beautiful couple. You are a match made in heaven.’ He stood up straight, holding the picture out as if to see it better. His hand grazed her breast. He gave her a steady look, then he tucked the picture under his arm.

‘If you speak to him, tell Amir we came by.’

Clarence let out a low whistle when he saw the cracked glass in the front door. ‘You want to get this fixed. It’s not safe, especially not in this neighbourhood. You can get yourself hurt if you don’t watch out.’

The three men left, her wedding picture in the armpit of a gangster. She wanted to laugh and she sat down to support her jelly legs. She heard their feet down the front path, then a car start up. They had been there less than twenty minutes, and something indefinable had changed. But what was certain was that they hadn’t come to leave a message for Amir. They knew he had left. They had come for her, to introduce themselves to her. To let her know that they were watching.