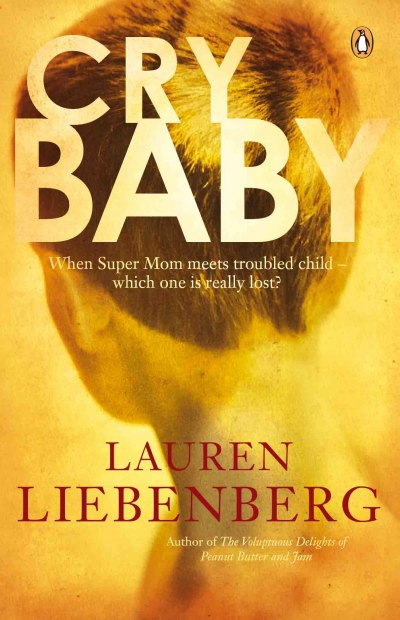

Information about the book

Maybe it was because he’d come straight from the Baron, but he’d been blind to the chafing between them earlier, at the party.

‘You turn up drunk for a date with me,’ Grace had said caustically when he’d walked into the bathroom where she was daubing plummy lipstick on puckered lips in the mirror above the vanity. ‘And you don’t even have the decency to apologise.’

God she looked yummy, in arse-hugging black pants and strappy high heels.

‘I am not even going to dignify that with a response,’ he’d said thickly.

He couldn’t tell if she was really pissed off or not. He’d showered and tried to act sober on their way up the hill to Andy and Debi’s.

When they’d arrived, Debi had pounced with a flute of something flushed and fizzy for Grace. Michael knew it would be Cap Classique; Andy wouldn’t cough up for French.

‘Oh, honey,’ she murmured to Grace, ‘didn’t we talk about that outfit?’

Debi looked as beautiful as ever, straight off a 1978 Springbok Hit Parade LP cover, her succulent cleavage delightfully indecent. They followed her wafting perfume out to the veranda where about four other couples mingled, but found their way barred by Andy and Mitch at the doorway. Mitch looked in worse shape than Michael did, leaning against the folded concertina doors and slopping some of his whisky as he shook Michael’s hand.

‘So, tonight’s the night then,’ Mitch said, sliding an over-familiar arm around Grace’s waist. ‘Just make sure you pull my keys out of the hat. I drive the E-Type. It’ll be a treat for you after the Hilux.’

Mitch, at almost fifty, was still ex-Marine lean and muscled. His petite, dusky wife, Carmen, was younger than Grace, than any of the other wives – the gaping age gap providing endless grist for speculation, if Mitch and Carmen weren’t there. She was chillingly Lolita-esque, Debi would say: ‘Also they look alike … I have said too much.’

‘I always knew it would be like this, Mitch,’ Grace said drily. ‘Boy meets girl. Boy wants girl to do wife-swapping. Girl says, “No way.” Boy says, “OK how about you just meet me in the toilets for a quickie?” Girl says, “Which toilet?”’

Apparently, she didn’t mind if Mitch was juiced up. Michael left her to be fondled by the dirty squaddie and made his way with Andy to the bar that hugged the river-stone-clad wall that enclosed one side of the veranda.

Andy pressed a glass of amber into his hand. Michael raised it to his lips and breathed deeply. The malt was laced with the sweet, sweaty smell of lust and the sourness of disappointment; it was soaked with the past, with the first throat-blistering taste of the forbidden, the furtive gropings and glorious oblivion of adolescence. Sometimes he missed the honesty of shivering in cold peaty fields, hugging his knees, swapping cigarettes and saliva and bottles of crème de menthe pilfered from the back of fathers’ drinks cabinets – drinking only to get drunk, blind drunk. To forget not the past but the future – O Levels, A Levels, Uni. One false move and that was it: you get to spend the rest of your life on the night shift in security at Tesco. Congratulations. Since he’d already been sacked for general shittiness as a security guard and also for falling asleep in the AstroTurf in the fruit-and-veg section of the ASDA in Birkenhead, he was properly frightened.

Andy grinned wickedly at him. Nick, Andy’s mate who was in the throes of divorce, tilted his glass at Michael in maudlin salute.

Michael was grateful that dinner parties with Nick and his ex-Stepford Wife, Louise, were probably a thing of the past. She’d run off with Teacher Lucy’s husband.

Beyond the bar, the veranda spread out in a wide expanse of travertine that spilled down shallow steps onto the lawn where shadows swallowed the flickering light. The profusion of candles – for Earth Hour, God help him – infused the air with vanilla and cinnamon and the tang of spices. The Cure throbbed through the overhead woofers.

More couples arrived and the party began to splinter. From his vantage point at the bar, Michael could more or less imbibe the flavour of any group without effort. The braces of men by the bar and around the braai were loosening up, the pissing contests giving way to Red Bull-ish camaraderie, the coed groups sizzled and spat, the treacherous women-only circles yoked their hapless victims into earnest convocation. It was faintly entertaining to catch snatches of the chatter:

‘Come on, Grace forget about book club. Book club is so last year. Why don’t you join the scheduled drug club I’m starting? We meet on Thursdays to discuss the side-effects of the drug of the month. You could be the founding member. What do you say?’

‘But what do you think is like the official definition of a sexless marriage?’

‘Fuck, I don’ know Nick. Just shut up.’

‘Your house is so boring!’

Mimi caricatured a snarky voice.

‘You don’t even have electric scooters and quad bikes and stuff. If my Wii was broken I’d just play my Xbox. I’m allowed to play PG games. PG rocks man.’

The other moms pursed their lips in shared disapproval.

‘I’m telling you, that is what he said to Kadin. I said to Kadin, “Kadin, does that make him better than you? Does it?”’

It was well-trodden ground, but this self-righteous bullshit wasn’t only the preserve of the women, actually. Dads-and-lads cricket matches and camp-outs at the school were larded with conversations about keeping the kids out of the malls. Malls and Xboxes were evil. The most sanctimonious among them would claim that his little prick got bored of his Nintendo but couldn’t keep his nose out of The Hardy Boys. Hidden behind the approving nods was the cherished conviction that everyone else was raising their spoiled brats with trashy Vegas values, while they had made their kid earn his bike.

Michael regularly told the boys that the youth of today made him sick.

‘You kids today, you don’t know how good you’ve got it. I mean, when I was a kid we didn’t have Xbox or Playstation III. We had the Commodore 64 with games like Pac-Man and Asteroids. Your guy was a little square. And there were no multiple levels, it was just one screen forever. And you could never win. The game just kept getting harder and harder and faster and faster until you died. Just like life.

‘TV? Let me tell you something, TV was crap. There was no Cartoon Network. You could only get cartoons on Saturday morning. Do you hear what I’m saying? We had to wait ALL WEEK for cartoons. It got better after ITV was launched, but back then there was no remote. You were screwed when it came to channel-surfing. You had to get off your arse and walk over to the telly to change back to BBC.

‘We had no cell phones, no internet. If you wanted to know something you had to hike down to the damn library and look it up, in the card catalogue, and make photocopies. If you wanted to slag some kid off, you couldn’t just go on to Facebook or BBM to do it, you had to do it to his face, on the playground. I hate to say it, but you wusses wouldn’t have lasted five minutes back in 1980.’

Today, childhood in middle-class suburbia was one long trip to Toys R Us, sprinkled with holidays to Disneyland, he thought, cringing – with us faithfully camcordering every ice-cream-filled moment from the sidelines. No wonder the kids though they were such hot stuff. He shook his head when he remembered Grace coaxing him into delivering long lectures to Ben about how his feelings mattered, how he didn’t have to do what he thought they wanted to please them. And God help them when those boys got hold of their first Visa card.

The mulled hum of the party was getting louder, punctuated by throaty laughter. Andy had flipped the playlist on the iPod to something with a higher tempo and upped the volume. It was only a matter of time before he stuck on Johnny Clegg’s ‘Impi’ and subjected them all to his white-Zulu routine.

Grace had been corralled by the women, but she clung to the fringes. There was no way, Michael knew, that she would join in Mimi’s conversation – not because Sam and Ben had had Xboxes and Nintendos since they were four, on which they played PG games flat out, but because her posse of mums included the alabaster-skinned stovepipe, Ophelia.

Ophelia was one of the mothers who’d gone behind Grace’s back to ask Teacher Veronica what she was ‘going to do about that Sam’ – kind of like what Grace had done about Jordan. But that wasn’t her crime, apparently: it was that she still greeted Grace in the car park as if they were BFFs, the snake. What did Grace expect, though? This was the woman who, when Teacher Lucy confiscated Craig’s Fizzer from his lunchbox, had made an appointment, with Bruce, to inform Teacher Lucy that she wasn’t paying her salary to victimise her child.

Now Grace was on the outskirts of the ring, giggling with a blonde with a very kissable pout, whom Michael didn’t recognise.

‘Oh my God Heather, he was hotter than Morten Harket. I had the biggest crush on him!’

‘No you didn’t. Your memory of high school is not that good, Grace. I had the biggest crush on him. When I crossed out all the corresponding letters in our names, I worked out that Heather Visagie loved Christian Blunden 87%, 93% if I took his last name.

‘OK, whatever, all I know is that when he started dating that wet dishcloth, Cindy, all I could think was, why? Why her, when he could have had me?’

‘You know he committed suicide right after his twenty-first? Well, they say it was suicide. He was riding his dirt bike across the sewerage aqueduct over the Jukskei when he fell.’

‘No he didn’t. I saw him at the reunion. He’s an accountant at Ernst & Young, married to Cindy, blah, blah, blah. Do you know what he said to me? When she came bustling over?’

She dropped her voice a few octaves.

“So Grace, you know this mare here has popped out three, hey?”

At which point, Grace nearly collapsed. She doubled over in mirth, clutching her belly, laughing weakly, spilling fizz, tears leaking out of her eyes.

‘Just think Heather, one of us could have been the mare who popped out three!’

As Michael watched Grace, he found himself strangely attracted to her.

‘So Grace what do you do now?’ Heather asked, sobering up.

Uh oh.

‘Oh nothing, I’m just at home with the boys now,’ Grace replied.

The rueful grimace, the faint shrug, the dismissive flick of her wrist, were all obligatory. Grace, like every other woman in her place, automatically apologised for what she did with her life, but not because she lacked Dr Laura’s militarism to defend it publicly. It had taken Michael years to crack the nuances of this conversation, but he was fluent now. The self-deprecation was bogus, most apparent if it was a woman doing the asking and if she responded with something like ‘Oh, really? I could never do that, myself. I practically ran back to work. Honestly, I so admire you.’

Grace may have still cringed inwardly when she had to write ‘None’ next to the colon after ‘Work Tel’, which was never even qualified with ‘if applicable’ on forms, but these cocktail-party moments were the moments that validated her. As the full-time mom, she would parry by ‘admitting’ that she loved being home with the sticky little goggas, without bothering to address the implication that she’d had a frontal lobotomy. In the mummy wars, the defensiveness was all on the part of the working mother. Securely entrenched on the moral high ground, Grace had no need for gratuitous jabs like ‘Honestly, I don’t know how you manage it. What is the after-care facility like at the school? Did little Johnny enjoy holiday camp?’

Of course, reality was more complicated. Women switched sides all the time, stopping work to be at home, or going back to work after staying at home, and more straddled the line, working part-time or flexi-time, or for themselves, often in cottage industries with pretensions. But now, after Grace had been tripped into disclosing her status first, Michael watched with interest to see how this conversation would play out.

‘And you Heather?’

‘I’m kind of a big deal actually. No, lie. I’m snap with you, but God, Grace, if someone had tapped me on my shoulder pads at our matric dance back in 1989 and shouted over the Depeche Mode that you were going to end up a housewife, I’d have squirted spiked punch through my nostrils.’

Grace went down for the count. It took her several moments to recompose her face while Heather blundered on.

‘Me either, Heather,’ she finally said. ‘When I think about it, it makes my blood boil. Can you name the worst crime perpetrated by the eighties? Your time starts now. Go!’

‘Hmm,’ said Debi, butting into their conversation, ‘home perms? Leg warmers? With stonewashed jeans? Sub-question: Is it in fact unfair to blame the rest of us for what Karl Lagerfeld and Bananarama – anyone, really, who featured on Pop Shop – should clearly be punished for?’

Grace made a honking noise. ‘Wrong. Brainwashing us into thinking that feminism was a dirty word.’

‘Well, I didn’t know you were going to go with a whole boring political angle. But you’re right, of course. What was the Cold War and apartheid next to the propaganda conspiracy waged by the right wing in its backlash against Jane Fonda?’

‘Careful Debi, you’re in danger of giving away your B. Soc Sci. All I’m saying is that we were raised to sneer at the bra-burners – I only ever heard the word “feminist” spoken sarcastically, with the aid of finger quote marks – and just look at us now. And not just at us, take a long, hard look around middle-class suburbia. We’ve come a long way, baby!’

‘Jesus, Grace,’ said Debi, ‘the stuff that comes out of your mouth. Who wanted to get lumped with all that man-hating and fisting and shouting Screw you, the patriarchy! Because, let’s face it, no-one would want to screw you, and your hairy pits.’

‘OK, so it had an image problem, but, still, what the hell did we think feminism was? What part of equality for women were we anti exactly? The right to vote? The right not to be men’s property? Equal pay? Was that just “not for you”, Debi, being valued the same as men, because the feminists were too butch?’

‘God,’ said Heather ruefully, ‘we thought we were the heirs of the women’s libbers, who’d fought so that we didn’t have to.’

‘Exactly. We weren’t going to change the world – because we didn’t think the world needed changing, plus it was “in” to scorn that corny Age-of-Aquarius stuff. Even when I sashayed off to work in my first bad Chanel knock-off and smacked up against the fat belt of men that still blankets every sector of the economy and government, I didn’t think I needed to think bigger than my own petty ambitions.

‘Now I see that denial is futile. If you stick your hand in your panties and don’t find a penis, you can congratulate yourself: you’re a feminist. By default. So we might as well sex up the label. I’m going to be a lipstick feminist from now on. It’s totally hot.’

‘Well I’m going to talk about “sexual politics,”’ said Debi, ‘which could be about blow jobs or threesomes or vajazzling. I mean, it could involve sex, which lightens the load when you have to listen to a whinge.’

‘Whatever the semantics, it’s time to stop pretending that my life is barely souped up from my grandmother’s,’ retorted Grace.

‘Men,’ said Heather. ‘Those bastards.’

‘Well, what else accounts for the fact universities have been funnelling out fifty-fifty ratios of graduates for decades and yet boardrooms are about as diverse as … as the men’s toilets? It is because of discrimination, in the sense that men control a system that still penalizes anyone wanting to balance the demands of children. And it’s motherhood that precipitates the mass desertion by women from the workforce–’

‘I’m a deserter,’ interrupted Heather. ‘Law firms worship the god of billable hours, and the whole corporate cult, with the rah-rah fests gobbling what was left of my time – it just got too much. Faced with rent-a-mommy or else downgrading from a career to a part-time but dead-end job, I quit. Well, I chose to stay at home with my baby. I was fortunate to have had the choice, although I still had to pay back my three months’ maternity leave.’

‘Some choice,’ said Grace bitterly. ‘But don’t worry, if we feel a bit resentful, we can always justify our choice to devote ourselves to our children by indulging in a spot of working-mum bashing. Victims of absentee parenting are to be pitied. Children need their parents – just not Daddy. He’s busy at a conference, in Mauritius, with free booze.’

Michael couldn’t stand it anymore, the shrill self-pity.

‘Oh for God’s sake, don’t be so naïve Grace. Have you been out of for so long, you don’t remember Ecos 101? It’s competition for the boss’s job that drives the ever longer hours.’

They all looked at him.

‘No, Michael,’ she said tartly, ‘I grasp that in theory it serves the profit motive and benefits the shareholders, which is why the culture has evolved, but I don’t think that productivity is a direct function of hours of toil, actually. Think about all that time spent slumped over your desk browsing TripAdvisor at the arse-end of the diminishing marginal returns curve. The hidden costs of all those long hours should damn well be accounted for, and not just in terms of low productivity. Surely even you can’t dispute that back-benching half the skilled labour pool comes at considerable cost to society? And to your sacred economy?’

She stuck out her tongue at him.

‘And make no mistake, there is a double standard,’ said Debi. ‘Look at Andy. When he’s not working, he trains for and competes in endurance sports. And what do you think his boss thinks of that? Hmm? Of the fact that he gets up in the dark every day and clocks an hour or two of training before even coming into the office, or that he pushes himself to get back out there even after a long day? Does he admire the ruthless discipline which drives Andy through competing claims on his time and energy, the superhuman time management that enables him to do it all?

‘Now, do you think he’d perceive him in the same way as a parent?’ she asked sweetly.

‘Behind all the lip service paid to “family values”, child care isn’t really valued at all,’ Grace added. ‘“Leaving to spend time with your family” is still code for getting fired.’

‘OK, so maybe institutionalised sexism is to blame for your shitty choices,’ Michael conceded mockingly. ‘But you know what I think, and I realize this is hazardous to my balls, but if you were really being honest with yourself, motherhood gave you an excuse, an honourable discharge, when your “career” wasn’t living up to your Hollywoodised expectations. Motherhood triggers the serious haemorrhaging of women out of the corner offices, or more likely, the cube farm, because it’s your get-out-of-jail-free card.’

Heather’s eyes widened. Grace’s blazed.

‘I guess he’s done being the whipping boy,’ Debi remarked. ‘For now.’

‘And if you hadn’t “sacrificed” your career for your children, maybe you wouldn’t be so desperately over-invested in them and their success.’

‘Ouchy, ouch!’ Debi winced.

‘No, no, he’s right,’ Grace’s voice had dropped to a husky growl. ‘So maybe I have been complicit in my own exile to 1950. Maybe I dumped the traditional burden of provider on you and enslaved myself to the mindless sentimentalizing of motherhood hawked by the media, but Michael, you’ve got as much chance of really getting what it’s like to be born into a world where money and power are massively skewed by sex, and slowly come to understand that that is so, and that you belong to the losers, as you have of getting rid of that beer gut. Or making another bonus over a bar, or never suffering “mechanical failure” again – oops!’

Women could be so cruel.

‘And Michael, darling, everyone unconsciously thinks of their child as their second chance, as “mini-me”, not just the mommies,’ Debi said patronizingly.

‘Ah! And this time, me will be perfect? Is that it?’ he enquired. ‘None of those ghastly humiliations from the first time around?’

‘Exactly. Those phonies who pretend they “just accept him for who he is”, and say stuff like “we just want him to be an ordinary kid”, are only lying to themselves.’

By this point, a heaving dance floor had opened up in the middle of the veranda, dispersing the groups of women. Mimi and a small huddle had retreated to the pool, but most of the others seemed to have been absorbed into the swell of dancers that had slowly pushed Grace and Debi and Heather out closer to the bar. Michael could feel the tremors of ‘The Whole of the Moon’ coursing through his body and his shirt clung to his skin in the wet heat. Suddenly Mitch and Greg surged off the dance floor, scooped Debi up between them and flung her into the swimming pool, drenching Mimi as they plunged in after her.

‘Ooh, she’s not going to like that,’ said Grace, biting her bottom lip.

As they left the party, Carmen reversed Mitch’s car into his, smashing the tail lights on the bull bar, whereupon Mitch pitched a hissy fit.

‘For fuck sake, get a grip,’ said Michael sardonically. ‘It’s only an E-Type.’

He’d seduced her when they got home by hoisting her up onto the bonnet of the Hilux. It was risky – could easily have ended in a let’s pretend this never happened moment, especially after half a jack of whisky, but still.

‘And keep those kitten heels on,’ he’d ordered.

She was woozy and resisted in a stop-it-I-like-it sort of way; he didn’t get that she was more sober and way more pissed off at him than she let on. He should have been suspicious when she’d refused on account of Thandi’s sleeping inside. They both knew that waking Thandi after midnight involved an uncomfortable tussle. She always eventually lurched upright with an animal noise.

It was only afterwards, in bed, when he was mocking her about being too repressed to try anal sex, that he figured out he’d been hustled.

‘You haven’t got a clue, have you Michael? I grew up in an era where sodomy was cast as the main threat to civilization as we know it – that and the Communists. It was single-handedly responsible for the collapse of the Roman Empire, you know. The fall of Rome was a big preoccupation around here. It all came down to moral decay. The rot set in when they let in …’ she swallowed, ‘the homosexuals.’

She hissed the word and shuddered.

‘You South Africans.’ He shook his head.

‘That’s why I felt much better after my mom slipped some book by James A. Dobson under my pillow, and I learned that we were staunching the tide of permissiveness – which could only lead to bestiality – and were resurrecting traditional values of decency in society.

‘That was what I found out in Veld School too. It was mandatory to go in Standard 5 and again in Standard 8. In between teaching us how to shoot, they showed us music videos of Chrissie Hynde doing a cover of ‘I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll’, and by fast-forwarding the Betamax tape on pause, you could actually see her pulling zap signs. We also learned that the ‘Bridge’ over troubled waters was really drugs, and then we studied the album covers of Iron Maiden and ACDC, who were well known satanists and sexual degenerates. They played the records backwards, but I only pretended I could hear the chanting about Beelzebub. Anyway, this kind of moral corruption was infiltrating South Africa – it was all a plot of the Communists. It was down to us not to let it pollute our minds. Then we prayed a bit and sang ‘Die Stem’.

‘Traditional fucking values.’

She paused.

‘Seriously, though, Michael, I just can’t get over running into someone from high school and seeing myself through their eyes: I’m a full-time mum, a dependent on my husband, and I’m proud of it – because nothing is more important than my children. Turns out it was just as well Home Economics was compulsory until Standard 8. Our project in Standard 6 was to sew an apron. In Standard 7 we knitted booties.

‘I don’t remember what I thought I was going to do with my life – well, actually I do: I was going to be the lead singer of Boney M. But even after I realised that dream was destined to shrivel and die, I was never ever going to end up claiming that raising children was its purpose. How the hell is that supposed to be fulfilling? So, your life is to prepare someone else for their life, for them to go forth into the world and do great things – unless of course, it’s a girl. She’ll need to stay at home to rear the next generation, of men.’

‘Oh God, Grace,’ Michael groaned. ‘Not this Germaine Greer shit again. Please. It sucks.’

‘Michael, I’m trying to be honest with myself about something I think I’ve been gagging for a long time. What you accused me of is true. I dropped out. Ugh! My ‘career’ was limping nowhere, and part of the reason is because I was a coward.

‘Remember all those studies in business school where the students’ opinion of a manager’s handling of an industrial dispute always correlated with whether the manager was named “Bill” or “Betty” – Bill was admired for his balls, Betty was a bitch? Looking back, I was always trying not to be Betty.’

‘Yeah, OK, maybe it’s because you served tea in the meetings, but maybe you quit because getting anywhere was all just too much like hard work.’

‘I don’t think you can accuse me of laziness Michael, I’ve slogged through our marriage and raising the children this far.’

‘So what are you saying? You wish you could chuck it all in, but what with you being such a chattel and all, you can’t. Is that it? What a drag, man.’

‘OK, sorry, I’ll take it back if you do. I’m admitting that I ran away from work, Michael, but can’t you admit that even the absence of overt discrimination doesn’t completely liberate women? After ten thousand years of subservience? My father was soldier, my grandfather was a gold miner, my great-grandfather was a missionary. What were my mother and my grandmother and my great-grandmother? Do you know, none of my teachers, at a girls-only school, ever acknowledged the absence of any great female minds anywhere in my entire education – not even one female poet in my anthology of English poetry, Chaucer to Donne. Not one. What do you think the effect of that is on a young girl’s psyche while she’s busy trying to look as fuckable as a Miss South Africa contestant and get invited to the St Stithian’s matric dance? Hmmn? And as for the story of St Ursula, our patron saint, and her company of virgins who were martyred after their gang rape by the Huns, let’s just not even go there.

‘You know,’ she added, after a pause, ‘I hate to admit it, but I evaded my stint in Credit Risk when I was still an intern because secretly I was so intimidated by the maths.

‘When I couldn’t hack it at work, because I was a ’fraidy-cat and couldn’t help playing nice, I admit, I consigned myself to the madness of perfect motherhood. Just like my mother – “who did everything, for you kids, everything.”’

‘And yet, you’re still being dishonest,’ Michael said drolly. ‘I know you. You do think that you, and only you, need to be there 24/7 to wipe their shitty backsides, or wallop their shitty backsides for that matter, and you love it. You’d think leaving them in institutionalised care or with a surrogate every day was cheating, that you can’t work and be a good mother, that there’s a point at which it is just a stark conflict between their interests and yours – and the guilt of pursuing your own ambitions at their expense, of effectively saying that when it came right down to it, I chose me, would kill you.’

He rolled towards her.

‘Now let’s talk back passage. Come on Grace, you know my motto: try anything once.’

‘Sod off, Michael. Don’t you get that for the first time, I’m really questioning my need to be Wonder-Mom?’

‘No you’re not.’

That was when he’d exhorted her to stop whining and blaming everyone else, and to do something with her life. He wasn’t sorry. It sounded an awful lot like victimization crap to him – it was funny how those who didn’t pay their own way resented those who paid it for them – and let’s face it, he wasn’t going to get anal sex that night anyway.

In his opinion, once you’d gotten over the crushing disappointment of your ordinariness – he’d bounced back from not being selected to take over from David Hasselhoff as the Knight Rider – there was nothing stopping you doing something with your life. Even if you were a woman.

‘Maybe you should, though, Grace. What do you think Sam’s straining against?’

She gasped in the darkness.

‘You’re the one who said he was a mirror. You said we needed to take a long hard look at what his behaviour was reflecting – we couldn’t blame it on some little punk on the playground. “Children are our teachers, Michael,” remember?’

Stress. That was the word that had got to him. She’d been going on about Sam’s erratic behaviour, the swings from victim to attacker, the recurring nightmares, and then she’d told him what the therapist who had been connecting the dots had said, about how a child’s hypothalamic response to stress can easily flip from flight to fight. Of course he got that kids acted out when they couldn’t express some emotional distress, but, somehow, putting it in terms of a physiological response – to adrenalin, to stress – had winded him.

After a long silence, she sat up and switched the bedside lamp back on. He pretended to be asleep, his head turned away from her on the pillow.

‘I know you’re still awake – you’re not snoring – but you can just lie there marinating in Jack Daniels if you want.’

He didn’t budge.

‘You know, Michael, maybe all this has freed me, and our sons. I understand – I am the one in the way. Maybe I’d be a better mother if I wasn’t trying to be a perfect mother. But even if I don’t want to play the supporting cast in my own life story, which is what motherhood comes down to in the end, what choices do I have now? Even if I decide I don’t want to spend the next ten years being a free concierge service for you or loitering in the school car park discussing how the stupid cow at Sorbet used gel not Gelish on my nails, there are no “on-ramps” to careers for women in their forties. You know that. I’d be competing against my younger self for a spot on the internship programme …’ She broke off, then added, vehemently: ‘James fucking Dobson is still out there demonising the working mothers so the rest of us martyrs to motherhood can justify our existence.’

‘So you’re still obsessed with James Dobson then.’

‘No, he just stands for all that patriarchal bullshit. Is he campaigning for a seismic shift in society’s concept of a work-life balance? For less and more flexible working hours? For using new technologies to redefine the “office” and reduce commuting time? For the adoption of real performance-based pay systems? For fathers to be parents? No. He suffers from a total lack of imagination. His only solution to the problem is that mothers must be emotionally blackmailed into staying at home with the children.’

‘Well, the man’s got a point,’ Michael quipped. ‘I think some of these dykes have forgotten what it says in the Bible, along with the bum-bandits, who deserve death for perverting the institution of marriage.’

‘Since we’ve proven that women can work and that men can parent, you’d think it wouldn’t be such a leap,’ Grace continued, ignoring him, ‘especially considering that the vast majority of breeding-age adults will eventually insist upon breeding. You’d think society would feel it’s in its collective interest to free up more of the workforce’s time to invest in the next generation, wouldn’t you? And if full-time after-school child-care was shared equally between both parents, the time off work would be, you got it, halved.’ She paused for breath.

‘But why should the old fart be the siren call for a new world order when the old one has served him and his cronies so well? It’s women who need to foreclose on this bloody deal. Younger ones don’t want to be associated with whining victimhood – until they become mothers and find out that’s what they are. So they sit around in meetings exchanging glances with the men as the working mother bolts out the door at five thirty (so she can still catch the last minute of Johnny’s soccer match) – the same men who spend two hours of the day in the Baron or the basement gym and are married to women who got condemned at fifteen to Standard Grade maths and Home Economics for matric, and who so jealousy guard the only title they’ve ever been entitled to. God, it’s about time we started setting fire to some more bras, especially maternity ones, with those cute little press-stud thingymajiggies.’

She twisted her wrist and pointed in his direction with a finger that wasn’t polite.

‘That’s right, assholes, this shit is over.’

He folded his pillow in half and punched the surface, as he did nightly, only more violently.

‘And if I have to watch your little pillow-fluffing routine even once more,’ she added gently, ‘I will stab you.’

Hours later Michael found himself staring wide-eyed at the vault of darkness. It wasn’t fair to blame Grace, and certainly not for being there for Sam too much. He knew that this arrangement had served him too, and, if he was ever in the mood for over-sharing, he might admit that, for all the power imbalance, he sometimes wondered if men weren’t the bigger losers. Still, something was wrong with Sam.

What worried him like a blackjack, more than Sam’s worsening behaviour, was a strange tic. He didn’t think that Grace had noticed – one of the paradoxes of being overwhelmed by worry or guilt, maybe, or merely of spending so much time with him – and unease censored him, but, more than once, Michael had come upon Sam going ‘Shush! Shush!’ with his hands clamped over his ears. The kid seemed frantic. One time, Michael had crouched down and asked Sam who he was shushing.

‘The voices, Dad,’ he’d said. ‘So loud. And that buzzing, buzzing noise.’

Michael pushed the thought away. He needed Grace, more than ever. And her loss of faith had towed an old nursery rhyme from the recesses of his childhood memories. Ring-a-ring o’roses. The needle was stuck on the last groove of the scratched old vinyl record in his mind:

A-tishoo, a-tishoo … We all fall down